The Channel Fleet Campaign – June-December 1780

The Channel fleet s 1780 campaign could not have got off to a worse start when on 18 May, a day after re-hoisting his flag at Spithead, the commander-in-chief Admiral Sir Charles Hardy died aboard the Victory. He may not have been universally esteemed, but in the previous year Hardy had successfully nullified both the mighty allied invasion fleet and the navy s own internal divisions caused by the political fallout from the Battle of Ushant in 1778. His untimely death created yet another crisis of leadership, just when it appeared that a welcome period of stability was to be enjoyed.

Vice-Admiral Hon. Samuel Barrington was the most enterprising and able candidate to replace Hardy, but the first lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich, was unable to convince this somewhat difficult officer to accept the role because Barrington still harboured a personal grudge against Sandwich over a perceived slight towards him. Barrington nevertheless continued to make his services available as second-in-command, with the caveat that he would serve any admiral bar the Tory Vice-Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser. His stance was indicative of the fact that the government s opponents dared not accept any senior position, although it was at least far removed from that of the leading Whig admirals, Lord Howe and Hon. Augustus Keppel, who following the Battle of Ushant fiasco had refused to serve at all.

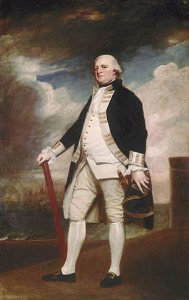

With their choices so limited the Admiralty invited the venerable but popular and non-political Admiral Francis Geary to assume command of the fleet on 22 May, whilst the appointment of the equally neutral but far more gifted Captain Richard Kempenfelt as captain of the fleet provided the technical ability and up-to-date thinking that the old admiral lacked. In addition to Barrington, Geary was blessed with a trio of capable junior admirals in Vice-Admiral George Darby, Rear-Admiral Hon. Robert Digby and Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart-Ross,

On 27 May Geary was ordered to sea with instructions to prevent a junction of the French and Spanish fleets that had been congregating at Brest, Rochefort, Lorient, Cadiz, Ferrol and Cartagena, but inevitable delays meant that his twenty sail of the line were unable to get away from St. Helen s until 8 June. Proceeding down the Channel, they were joined by the Cumberland 74 and Alfred 74 which came out from Plymouth, and eventually the Grand Fleet , as it was often known at the time, would consist of over thirty sail of the line including nine mighty three-deckers.

From 15 to 27 June the fleet cruised off Ushant before sailing on to the Bay of Biscay in search of the enemy. Information as to the allied movements was non-existent however, and it was not until 29 June that Geary received news from the Admiralty that Commodore George Johnstone, commanding off the coast of Portugal, had learned of two Spanish squadrons consisting respectively of four sail of the line and two frigates, and seven sail of the line and three frigates, which had been sent to sea to intercept the British East and West Indian trade.

Rather than detach any individual squadrons to run down the Spanish, as he had been instructed to do by the Admiralty, Geary and his senior officers decided to keep the fleet intact so that they could tackle any combined allied force. This decision appeared to be justified when at 10 a.m. on 3 July, whilst the fleet was sailing south towards Cape Finisterre, the Monarch began signalling the presence of a strange fleet of some twenty-five to thirty sail in the distance. Amongst the British officers there was some hope and expectation that this was an allied armada.

The difference between the old school Geary and the innovative Kempenfelt immediately became apparent when upon receiving the news of the appearance of the strangers the captain of the fleet stepped into his cabin. When he reappeared it was with his treasured signal book, and this he carried with reverence and purpose to the binnacle. Carefully laying it open, and with his brilliant mind already planning the various evolutions and manoeuvres that would bring about a general action, Kempenfelt suddenly found his hand affectionately squeezed by the commander-in-chief who promptly shut the book. Now, my dear friend said the cheerful Geary, whose idea of an action was to sail straight into the enemy and engage him at musket range. Do pray let the signals alone today, and tomorrow you shall order as many as ever you please.

But there was to be no battle, for rather than the allied armada that the British had been seeking, the strange fleet was in fact a French convoy from Haiti under escort of the Fier 50 and another large ship en-flute. An all day chase followed, and by 5 p.m. the Monarch and Foudroyant had passed the stern-most of the convoy and were ploughing ahead in the hope of bringing the enemy men-of-war to action. Unfortunately a fog set in two hours later, but Geary kept in with the convoy overnight, and come the morning, although the Monarch and Defence were out of sight in a fruitless pursuit of the Fier, a dozen prizes were secured carrying cargoes of sugar, coffee, indigo and cotton to the value of over one hundred thousand pounds.

From 10 to 20 July Geary continued to cruise uneventfully off Cape Finisterre before he decided to retire to Ushant so as to better protect any incoming British convoys. Here on 2 August he fell in with a valuable out-going convoy under the command of Captain John Moutray of the Ramillies 74, and the fleet escorted it to a position one hundred and twelve leagues west of Ushant before seeing it on its way. On 8 August Geary decided to return to Spithead to re-victual his ships and to land over two thousand men who were sick with scurvy. Unfortunately for his country, but through no fault of his own, the greater part of Moutray s convoy was captured a day later by a Franco- Spanish fleet of thirty-two sail of the line that had come out of Cadiz. The financial loss would dwarf the 100,000 taken by Geary s fleet.

Arriving at Spithead on 18 August, the fleet was not allowed to tarry long for fear of the French and Spanish running down any more convoys, and to that end Rear-Admiral Digby s detachment of a dozen sail of the line was quickly ordered back to sea with instructions to cruise in mid-Channel. Meanwhile Admiral Geary s health was little better than that of his men, and after a brief convalescence ashore at his residence in Polesdon, Surrey, the commander-in-chief was obliged to resign his post. Once more Barrington was ordered to undertake the command of the fleet, and once more he refused. Instead he handed the command over to the port admiral at Portsmouth, Sir Thomas Pye, pending a further appointment, whereupon the King, who felt that Barrington was playing politics, immediately ordered him to strike his flag and come ashore. On 7 September a safe pair of hands in Vice-Admiral George Darby was promoted to become the new commander-in-chief, and he was also appointed a lord of the Admiralty shortly afterwards. Crucially, Kempenfelt retained the position of captain of the fleet.

Putting to sea on 12 September with twenty-three sail of the line that included Digby s squadron whose detachment had been cancelled, Darby initially sailed for Torbay where he remained wind-bound for six weeks. It was not until the end of October that he was able to get away again, having lost two ships through storm-damage in the interim. However, his newly drafted orders to intercept the French West Indian fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral Louis-Urbain de Bou nic, the Comte de Guichen, were negated by this body s previous arrival in Cadiz, bringing the strength of the allied armada in that port up to a monumental sixty-four sail of the line.

By now however the winter season was beginning to take its traditional toll upon all three fleets, and on 7 November the French withdrew their thirty-eight sail of the line from Cadiz in order to refit them for the following year s campaign. The fleet eventually reached Brest two months later. In the meantime, after an uneventful five weeks cruising off Cape Finisterre, Darby returned to St. Helen s on 21 December. It would be another three months before he put to sea again.

The fleet that departed Spithead on 8 June: