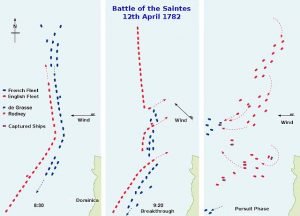

Battle of the Saintes – 12 April 1782

Shortly after daylight broke on 8 April over the British Leeward Islands fleet at anchor in Gros Islet Bay, St. Lucia, a message was rushed below to the commander-in-chief, Admiral Sir George Rodney, in the great cabin of his flagship Formidable 98. Information was being received from his scouting frigate, the Andromache 32, Captain George Anson Byron, that the French West Indian fleet had departed their base at Fort Royal, Martinique, some thirty-odd miles to the north, the day before.

The French fleet was under the command of Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse-Tilli, and in addition to carrying an army of five thousand five hundred men commanded by François Claude Amour, the Marquis de Bouillé, it was escorting a richly laden homeward-bound convoy out of the Leeward Islands. The two commanders were thereafter looking to join with around fifteen thousand allied troops and twelve Spanish sail of the line at Cap François in order to launch a long-planned assault on the jewel in the British crown, Jamaica, and thus on both counts they were determined to avoid any contact with the British fleet.

Leaving the under-repair Shrewsbury behind, Rodney’s thirty-six ships were under way by noon, and at 2.30 p.m. his outlying frigates identified the French armada standing to the north-west. Numbering some hundred and fifty vessels, the slow-moving French could not hope to out-sail Rodney’s men-of-war, and by the time they crawled past the island of Dominica at sunset they were visible from the mastheads of the British fleet. A lack of wind left both fleets struggling to make progress throughout the night, but by dawn the British van of eight ships under Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood was about four miles to the south-west and leeward of the French rear, which was now becalmed in the lee of the high hills of Dominica. Meanwhile the head of the French line, numbering more than a dozen sail of the line, was some twelve miles to the north and clear of Dominica in the channel that separated it from the French island of Guadeloupe.

With the morning drawing on a north-easterly breeze got up, and this allowed the French van in the channel to windward, and then Hood’s ships in the south, to manoeuvre. As the British second-in-command edged north, so the Auguste 80 and Zélé 74, which had become detached in the north-west from the French fleet, cut across his line in order to regain their consorts. This move forced the Alfred 74 at the head of the British line to bear up, and although the respective officers chivalrously doffed their hats at each other no guns were fired on either side, for as far as the scrupulous Hood was concerned Rodney had not yet made the signal to engage.

de Grasse now despatched the convoy and its escort consisting of the Expériment 50, Sagittaire 50, and frigate Isis northwards to Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe and shortly after 8.30 he tacked his fleet and stood to the south. Although it was intended that his superior sailing fleet would escape eastwards through the channel between Dominica and Guadeloupe in order to secure the safety of the convoy and proceed on his mission to Jamaica, he firstly wanted to take advantage of his sudden superiority over Hood by launching those ships that weren’t becalmed under Dominica at the detached British van.

From 9.30 to 10.30 Hood’s outnumbered ships suffered a constant if long-range fire from half of the French fleet led by the commander of the van division, de Grasse’s second-in-command, Vice-Admiral Louis-Philippe Rigaud, the Marquis de Vaudreuil. In prosecuting their attack, the French skilfully ranged along Hood’s line from their windward supremacy before circling back to renew their bombardment, whilst all the while ensuring not to get within range of the British carronades. Hood could do little but fight back against these odds whilst Rodney’s centre and rear lay becalmed and frustrated in the lee of Dominica, and many officers suggested that the rear admiral had unwisely taken his ships beyond support.

When the wind did reach the centre of the British fleet at about 11.30 the Formidable, being ably supported by the Namur 90 and Duke 98, came up to the north on the starboard tack and engaged the French at long range with little advantage to either side. This move did nonetheless oblige de Vaudreuil to rejoin the French fleet in their rear so as to avoid being cut off. Having united his fleet de Grasse next wore on to the same tack as Rodney, but as Hood’s ships were still marooned, he decided to throw his van into the fray once more. The Warrior 74 and the Royal Oak 74, which had only just regained her rightful position at the head of the British line, received most of the renewed fire from 12.14, but once again the British centre and rear were eventually able to come to the rescue, and shortly after 1.45 de Grasse threw up his attack.

During the action that morning Captain Bayne of the Alfred had been a fatal casualty, his leg being carried off at mid-thigh by a chain shot. Amongst the British van the Royal Oak and Montagu 74 were in poor shape, whilst a gun had exploded on the French Caton 64 causing eighty casualties and obliging her to bear away for Guadeloupe. Tactically de Grasse’ s wishes to avoid a full-scale battle had been fulfilled, and with the tail end of the convoy disappearing from view to the north by 6 p.m. it was clear that he was going to succeed in protecting it from the British fleet. To the contrary however he had failed to take advantage of a golden opportunity to overwhelm Hood’s division with his entire fleet, something which would have tipped the scales in his favour if and when it came to a full-scale battle.

Following this skirmish, the British fleet redressed itself with Rear-Admiral Francis Drake commanding the van, Rodney the centre, and Hood’s damaged ships the rear, and after effecting repairs during the night they resumed their pursuit of de Grasse on the morning of the 10th. By now the superior sailing French vessels were about twelve miles away to windward, heading east under easy sail in order to thoroughly ensure the safety of the convoy whilst apparently disdaining an action. Soon Drake felt compelled to send the frigate Andromache back to Rodney with a note seeking clarification of his instructions, for contrary signals had been running up the flagship’s halliards including one that had ordered a ship in the van to reduce the meagre sail she was already carrying.

Slow progress was made throughout the rest of the day, but when Sir Charles Douglas, the captain of the fleet and renowned gunnery expert, inexplicably ordered the British fleet to shorten sail during the ensuing night it allowed the French to be far distant to windward when dawn broke on the 11th. By noon that day the French were to windward of a small archipelago in the channel between Dominica and Guadeloupe known as Les Saintes, and the British van under Drake, which had passed so close to Guadeloupe that they could identify a 64, 50 and three frigates in port, were suffering damage to their sails in what appeared to be a vain pursuit.

Fortunately, the French had also suffered a calamity during the night when the habitually careless Zélé 74 had collided with the Jason 64. The latter vessel was forced to withdraw towards Basse Terre whilst the former, without her fore topmast, began falling off to leeward in the company of the Magnanime 74. Their gradual detachment from the main body of the French fleet hastened a spirited British pursuit in strong breezes led by the Magnificent 74, and towards the end of the day de Grasse had to bear down to protect his errant duo, thereby losing most of the ground he had gained over the previous two days. It was to be a move he quickly regretted, for no sooner had the Zélé rejoined the French fleet after dark than she ploughed into the flagship Ville de Paris 110, losing the rest of her foremast and bowsprit and falling off the wind once more.

That night the British fleet remained on the larboard tack, heading in a southerly direction on a south-easterly wind until 2 a.m. on the morning of the 12th when it tacked. Come dawn the French fleet was spread out some ten to fifteen miles away to the north-east and to leeward off Les Saintes. To the west of the French and north of the British, and a mere six miles from Hood’s rear division, was the dismasted Zélé heading towards Guadeloupe in the north-west under tow of the frigate Astrée. The Ville de Paris was between the Zélé and her own fleet, and about eight miles from the British.

At about 6 a.m. Rodney despatched four of Hood’s ships, the Monarch 74, Valiant 74, Centaur 74 and Belliqueux 64, in pursuit of the Zélé, to which de Grasse responded by signalling his fleet to close with the Ville de Paris whilst he set off to discourage the pursuers. Rodney ordered the fleet to form in a north-east to south-west line of battle on the starboard tack and returned to his cabin to rest, and he was still there when his officers noted with delight that the French fleet had come about in reverse order to head south on the larboard tack. That they had to undertake this manoeuvre in the narrow channel between Dominica and Guadeloupe whilst already scattered in a disorderly fashion over several miles caused great difficulty to the rear of their fleet, and this was notwithstanding the fact that a number of their more perceptive officers could not believe the risk de Grasse was taking in exposing their fleet to an engagement.

Sure enough, by 7 a.m. in foggy conditions, these favourable circumstances together with a wind that had stubbornly failed to veer away from the south-east to the expected east, made some sort of engagement inevitable. Sir Charles Douglas rushed into Rodney’s cabin to tell him ‘I give you joy Sir George, Providence has given you the enemy on the lee bow.’ Yet it remained to be seen how far de Grasse would commit himself in falling off to leeward for the sake of the Zélé, for if he favoured maintaining the weather-gauge then nothing more than a passing cannonade would immediately ensue.

By now the forces ranged were thirty-six British sail of the line against thirty French. Rodney ordered his fleet to close up whilst recalling Hood’s flying squadron, and as the two battle lines converged on their opposite tacks the light breeze shifted at last into the east, throwing the French line slightly more to the south south-east. This development caused no little disappointment amongst Rodney’s officers, for it now seemed that the engagement would be no more than a passing cannonade that would see the leading French ships already out of range by the time the two fleets reached the point of convergence. The commander-in-chief could do little more than signal the fleet to ‘Engage the enemy more closely’ and then wait to see what transpired. In the meantime, the Zélé in the north-east was largely forgotten.

At 7.40 a.m. the Marlborough 74, leading the line on the opposite course to the French, was able to haul towards the north north-east, being parallel to the ninth ship in the enemy line, the Brave 74. At 7.57 she began firing at this vessel, to be followed in succession by the rest of the fleet as it engaged the French centre and rear at pistol shot. Within a half-hour all the British ships down to the Formidable, lying eighteenth in the British line, would be in action.

For four days the British had been spoiling for a fight and now they ruthlessly seized the opportunity, pouring a well disciplined but furious fire into the French ships. The aptly named, gout-ridden Captain Henry Savage of the Hercules 74, forsaking his normal chair on the quarter-deck, added his own personal venom through his speaking trumpet, balling his fist at each Frenchman as they came abreast of his ship. Although wounded and taken below deck he was soon back at his post sitting on a chair to continue the tirade of insults and abuse, and his behaviour was symptomatic of the sheer British aggression. This was somewhat comically although inadvertently replicated on the Formidable where a bantam-cock, released from its coop by a shot from the Ville-de-Paris, roared its own defiance at the enemy from the poop rail. Rodney, delighting in the battle to such an extent that his own gout was temporarily forgotten, sucked happily on a lemon from his chair on the quarterdeck and cheered on the bird. Of far less levity however was the sight of frenzied sharks seizing upon the bodies that tumbled out of the ships as the combatants cleared the dead from their decks to ensure the guns could be worked.

de Grasse responded to the threat of the entire British line overwhelming his centre and rear by ordering the hitherto largely unengaged eight leading French ships under Vice-Admiral Louis Antoine, the Comte de Bougainville, to put their helms up and attack the approaching British rear. However, on these French ships there was confusion as to why de Grasse was making this manoeuvre, as it was taking them further into the doldrums surrounding the high hills of Dominica. Perhaps as a consequence the French van did not serve de Grasse well, for one ship, the Palmier 74, took up a station to windward of the Northumberland 74 that necessitated her to fire through the latter’s rigging at Hood’s rear ships, whilst the Neptune 74 and Brave 74 failed to close with the enemy, the Souverain 74 was tardy in doing so, and de Bougainville’s flagship Auguste 80 simply did its own thing.

By nine o’clock the two flagships, Rodney’s Formidable and de Grasse’s Ville de Paris, had furiously engaged one another before passing on. In Drake’s division the action had been warm, with damage aloft substantial yet casualties light apart from aboard the Prince George 98, which had suffered nine men killed and twenty-four wounded. As the last of the ships in the van passed beyond the extremity of the French line some of them hove too in order to effect repairs. Captain Thompson of the America 64, whose command was twelfth in the line, was the first captain to wear ship without orders to pursue the French, but then he wore again and assumed his original position in the absence of any instruction to do otherwise. The recently promoted Captain Saumarez of the Russell 74, the last ship in Drake’s van division, showed no such inhibitions, and after wearing initially with the America at 9.00 he continued on his course to windward of the French to rejoin the action.

Nevertheless, it was likely that within twenty minutes the two fleets would pass each other on their opposite tacks, and with the French to windward it was apparent that they might be able to make their escape after all. Rodney must have been contemplating this fact when after exchanging shot with the Ville de Paris’ second, the three decked Languedoc 80, and her next ship in line, the Sceptre 74, the Formidable was engaged by the nineteenth placed ship in the French line, the Glorieux 74.

A sudden change in the wind back to the south-east at 9.15 caused the French line to fall away to leeward in order to keep mobile, and in the confusion of battle Sir Charles Douglas noted that this had allowed a gap to open in the French line behind the Glorieux. When Rodney re-appeared on the quarter-deck after visiting his stern galley to study the situation aft, he found Douglas positively insisting that they steer into the gap, thereby breaking the French line and seizing the weather-gauge. At first Rodney refused to do so, but after a short consideration he allowed Douglas to proceed. For the first time in a century a line of battle would be broken.

As the Formidable steered into the gap behind the Glorieux she engaged both her and her second, the Diadème 74. The crew of the Glorieux, which ship had already been badly damaged by the Duke and had lost her captain, the Vicomte d’Escars, instantly realised the precariousness of their position, and many fled below deck as the British flagship’s mighty broadside pulverised her from stern to stem, fatally injuring all her masts. Following Rodney through the line and firing successively into the beleaguered Glorieux were the Namur 90, St. Albans 64, Canada 74, Repulse 64 and Ajax 74. The carnage they caused was horrendous, but although the Glorieux was totally dismasted within fifteen minutes the British would later testify to her proud and bold resistance, as typified by her first lieutenant, Jean-Honoré de Trogoff de Kerlessi, who nailed his ship’s colours to the stump of a mast.

Meanwhile another gap had opened in the French rear between the Réfléchi 64 and Magnanime 74 allowing the Duke, which had been next ahead of the Formidable, to sail through their line. Without any vessels to support her she was put in jeopardy when a determined assault by the Destin 74 was followed by a raking broadside from the Magnanime and then further attacks by the Diadème and Réfléchi. The French would later claim that she struck her colours to de Vaudreuil’s flagship Triomphant 80, but in the event Captain Gardner’s ship was rescued from her predicament when the Formidable and Namur moved up to bombard the four French ships at close quarters.

As the smoke temporarily cleared it could be seen that Commodore Affleck’s Bedford 74, the last ship in the centre division, had passed into the gap between the twelfth placed French ship, the César 74, and the thirteenth, the Dauphin Royal 70. Hood, whose flagship Barfleur 98 had got into action at 9.25, then took his thirteen ships into the Bedford’s gap and through the French line, dispensing a good deal of punishment to these two French vessels and the Hector 74.

By now de Grasse had realised the desperate situation of the Glorieux, and by bringing his flagship to her relief he allowed her to be taken in tow by the frigate Richmond, herself a recent French capture from the British. But in no time at all the hungry British set about the Glorieux once more, and preferring the Richmond not to share his own ship’s inevitable fate the formidable de Kerlessi cut the tow rope with his own hand and resumed firing.

With the smoke enveloping the battle it became increasingly difficult for the respective commanders to take stock of their dispositions, and it was not until a fresh easterly breeze sprung up at 1p.m. that they could gain some clarity. Now it could be seen that the French van was some two miles to windward of de Grasse and the half-dozen or so ships he had in company, whilst the rear under de Vaudreuil was about four miles to leeward. Alone and exposed, the César and Hector were between de the French van and the British to windward, whilst the battered Glorieux was to windward of the Ville de Paris. At 1.15 de Grasse signalled his fleet to re-form their line of battle on the larboard tack with the intention of isolating Hood’s ships, and this he repeated forty-five minutes later. But again, the van under de Bougainville let him down with only the Souverain making a half-hearted attempt to obey before she gave up. In effect the French van was now out of the battle.

The three British divisions were in a better order which allowed them to reform around their commanders and begin preparations to mop up the isolated French ships. Hood typically showed the most expedition by getting his boats out to tow the Barfleur’s bow around towards the French, but although he expected Rodney to make the signal for a general chase, he noted to his amazement that the signal for ‘close action’ was still flying. Determined to make what captures he could from the dominant position in which the fleet found itself, he ordered his own ships to chase, and at 2 p.m., with the breeze getting up, he hoisted studding sails on his flagship. Other vessels, in particular from the latter end of Rodney’s centre, then joined the chase.

The Royal Oak soon received the surrender of the battered Glorieux, whilst the Bedford and Centaur caught up with the César, forcing her to submit in mid-afternoon. The Canada got into close action with the Hector and had the satisfaction of seeing her men temporarily flee for cover before Captain Claude Eugène Chauchouat de la Vicomté inspired them to fight back. His valour soon cost him his own life, and with the arrival of the Alcide 74 from the British van the shattered Hector surrendered to that ship at about 4.30 after an honourable and brave resistance which saw six feet of water flood through the shot holes into her hold.

Having failed to reform his line on the starboard tack after further signals at 3.30 and 4.00, de Grasse found his flagship in the vicinity of just three ships from the centre, the Languedoc 80, Couronne 80 and Sceptre 74, and five from the van, these being the de Vaudreuil’s Triomphant 80, the Bourgogne 74, Pluton 74, Magnifique 74, and Marseilles 74. When it became clear that the British were targeting the Ville de Paris two of her larger consorts, the Couronne and Languedoc took flight, and although de Vaudreuil offered to take the flagship in tow de Grasse refused. Bravely, the Ardent 64, a French capture from Vice-Admiral George Darby’s Channel fleet in 1779, came up to support her flagship, but she was easily overpowered by the Belliqueux and Prince William from the British rear and forced to surrender at 6.20.

Alone, the Ville de Paris, her rigging in shreds and her rudder disabled, managed to repel attacks from the Torbay 74, Canada 74, Monarch 74, Marlborough 74 and Russell 74, before being pulverised into submission by a ten-minute assault from Hood’s Barfleur shortly prior to sunset at 6.29. The ship had lost three hundred men killed, and apart from the tall and imposing de Grasse there were just two other men still on their feet on the upper deck. It was the admiral’s hand that struck the colours, and upon his flagship being boarded by men of the Formidable he proffered his sword to Captain Lord Cranstoun. The ship was the first ever French first-rate to surrender, and although her men had literally been scraping the gunpowder barrel to keep her in action, it would hurt French pride the more that she had been presented to the king as a result of a patriotic appeal in Paris.

With darkness coming on Rodney, languishing a half hour behind Hood, ordered his ships and their prizes to heave to for the night, an instruction which was much to his immediate subordinate’s displeasure. Yet although fiercely criticised by Hood for failing to follow up on his success Rodney had won a brilliant victory, and it was one that had been embellished by the capture of de Grasse, the first French commander to be taken in combat. Whilst de Grasse had suffered for a want of support from his van, Rodney had kept his own force intact despite many of the ships being in poor repair, and the discipline he had strived to impose over the previous two years of his command had at last borne fruit.

The French were pursued in vain until the next morning by the Bedford after she had failed to see Rodney’s signal, and thereafter they scattered in various directions, with five vessels under Bougainville not stopping until they reached Curaçoa on the South American mainland. de Grasse was chivalrously allowed to remain aboard his captured flagship during the night of the 12th before being taken aboard the Formidable the next day. He enjoyed an easy relationship with his captors and blamed his defeat on the abdication of their duties by his officers, in particular the courtesan Bougainville. Later, as a feted and popular prisoner in London, he would produce a severe indictment of those he perceived to be the guilty men, and this led to the captains of the Languedoc and Couronne being imprisoned until they could be brought to a court martial in 1784. Much to de Grasse’s horror the verdict exonerated these officers, and although he sought a re-trial this was denied him. Instead, he was informed by the minister of marine that King Louis considered de Grasse himself to be culpable for the defeat, and he was thereafter banished from the French Court.

Over the five days following the Battle of the Saintes the British refitted off Guadeloupe whilst they lay becalmed, but when the winds eventually returned on 17 April Hood with ten sail of the line was despatched in chase of the French stragglers. Two days later five vessels were spotted in the Mona Passage between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. The Valiant outsailed all her consorts bar the Belliqueux, and with imperviousness to the risk of going aground she crossed the shoals off Cape Roxo in such little water that her keel drove through soft sand. This boldness paid dividends, for she was then able to bring to action two of the French ships that had been damaged before the battle and sent on their way to Basse Terre. The first was the brand new Caton 64, and having managed to rake her at 3 pm the Valiant enforced her surrender without encountering any resistance. She then went on to capture the equally new Jason 64 after a forty-minute fight. The frigate Aimable 32, which had been chased by the Magnificent 74, fought off her greater opponent for over forty minutes before succumbing, and the sloop Cérès, which struck to the Champion 24, was also taken. The fifth vessel escaped under chase of the Prince William and the Warrior.

The Comte de Vaudreuil assumed command of the reduced French fleet after the Comte de Grasse had been defeated.

These prizes were added to those ships that had been taken on the day of the battle; the Ville de Paris, Glorieux, Hector and Ardent. Unfortunately, the captured César had blown up and sunk with the loss of some four hundred men and her British prize-crew of fifty after one of the French had inadvertently set a barrel of spirits alight during a drunken binge below decks, and neither did the Ville de Paris, Glorieux and Hector survive long in British hands as they were destined to founder in a hurricane whilst under convoy for England that autumn.

The French suffered over two thousand men dead and wounded during the battle, which was a testament to the ferocity of an engagement that had seen the Formidable alone unleash eighty broadsides. Amongst the French losses were six captains; Jean Isaac Chaudeau de la Clocheterie of the Hercule who had so gallantly commanded the Belle Poule in her engagement with the Arethusa in 1778 Antoine Crespe de Saint-Césaire of the Northumberland, Claude Eugène Chauchouat de la Vicomté of the Hector, Charles René Louis Bernard Vicomte de Marigny of the César, Jacques François de Pérusse, Vicomte d’Escars of the Glorieux and Jean François du Cheyron, Chevalier du Pavillon of the Triomphant. British losses were two hundred and forty-three men killed and eight hundred and sixteen wounded. Three captains lost their lives, William Bayne of the Alfred, who had been killed on the 9th, William Blair of the Anson who died in the first stages of the battle, and Lord Robert Manners of the Resolution who had been terribly wounded in the legs, chest and arm at 8.45 on the 12th, and had lost his battle against fatal wounds a week later whilst take passage home to England aboard the Andromache.

The remnants of the French fleet eventually reassembled at Cap François under the orders of the Marquis de Vaudreuil where they joined their erstwhile convoy and the Spanish, but with disease rampaging through the army camp the deaths of thousands of soldiers caused the proposed invasion of Jamaica to be abandoned. Having been rejoined by Hood off Cape Tiburon, Rodney left his deputy in command of twenty sail to watch the remaining French ships at Cape François and he sailed for Jamaica with the remainder of his fleet and the prizes. de Grasse then left that island in May aboard Vice-Admiral Peter Parker’s flagship Sandwich 90 which was returning to England with a convoy.

In the meantime, Captain Lord Cranstoun had been sent home aboard the Andromache with despatches bearing an account of the victory, and after being landed at Ilfracombe on 17 May he arrived at the Admiralty the next morning in the company of Captain George Anson Byron, whose frigate had proceeded to anchor off Portishead, near Bristol. A relieved king raised Rodney to the peerage, Hood too was ennobled, and Drake and Affleck were both rewarded with baronetcies. Yet in his hour of victory Rodney’s renowned avarice came back to haunt him, for the new government had found his earlier behaviour at St. Eustatius so distasteful that they had already despatched Admiral Hugh Pigot to replace him. After succeeding to the command at Jamaica on 10 July Pigot took the fleet to North America for the hurricane season, came back to Barbados in October, and then left Hood with thirteen sail of the line to watch the enemy at Cap François.

Rodney’s success in wresting control of the Caribbean from the French and paving the way for a more favourable peace treaty could not be over-estimated, despite Hood’s whinging about his failure to take more French prizes. True, the American War of Revolution might have been lost in so much that the colonies had all but gained their independence, but a defining battle with the French had needed to be won to secure the British West Indian Islands and to obtain a peace with honour, and Rodney had emphatically achieved that.

Ships participating and casualty figures:

Ships serving with the Leeward Islands fleet but not present at the battle:

| Prudent 64 | Captain Andrew Barkley |

| Endymion 44 | Captain Edward Tyrrel Smith |

| Nymphe 36 | Captain John Ford |

| Lizard 28 | Captain Edmund Dod |

| Fortun e 40 | Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian |

| Convert 32 | Captain Henry Harvey |

| Pegasus 28 | Captain John Stanhope |

| Zebra 16 | Commander John Bourchier |

| Germaine 16 | Commander George Augustus Keppel |

| Alert 14 | Commander James Vashon |

| Salamander fs | Commander Richard Lucas |

| Blast fs | Commander John Aylmer |

French fleet:

1 x 104 guns: Ville de Paris:

5 x 80 guns: Auguste, Languedoc, Couronne, Triomphant, Duc de Bourgogne;

20 x 74 guns: Hercule, Souverain, Palmier, Northumberland, Neptune, Scipion, Brave, Citoyen, Hector, C sar, Sceptre, Glorieux, Diad me, Destin, Magnanime, Conqu rant, Marseillais, Pluton, Magnifique, Bourgogne:

1x 70 guns: Dauphin Royal;

3 x 64 guns: Ardent, Eveill , Refl chi:

Frigates: Richmond, Aimable, Amazone, Galath e.

A battle map would be very helpful.

Hi Dave – thanks for getting in touch. I normally struggle to provide images / maps etc as they cost money to downloaded and I am unfunded, however I’ve noticed that there are some maps relating to the Battle of the Saintes on Wikipedia which are free to download, so i’ll take up your suggestion and post them to the article. Cheers, Richard.

I have read about the battle between the English and the French ships. I found it fascinating even

though I am not well up on the history of the battle.

However I do have a beautiful framed print of the battle original painting by Richard Paton

and I was curious to know more about it.

Hi Marjorie – than you for getting in touch, and I hope my article helped! I would love top see an image of your painting if that is possible. kind regards, Richard.

Hi,

Whilst recently exploring my family tree I find some of my forbears on my mother’s side,

the Wilsons, lived in the Shire of Rodney from approx. 1870.

The Shire is located approx. 180 kilometers north of Melbourne, Australia. As I understand, it was named after Sir George Brydges Rodney.

After some research into the life of this British Navel Officer I am unable to throw any light on why this small shire in rural Victoria would be named after him.

Regards, Puzzled

Hi Maxwell, thanks for your message. Unfortunately I can’t even find your ‘Rodney’ on Google Maps, so am similarly puzzled. Of course scores of towns in Australia were named after Georgian Naval heroes, the most famous being Fremantle and Brisbane, but these were mainly coastal. Perhaps it was simply the case of a patriotic Victorian-age Victorian wishing to honour one of our great naval heroes, or maybe there was a connection with Alresford in Hampshire where Rodney lived a greater part of his life?