The Channel Fleet Campaign – June-November 1781

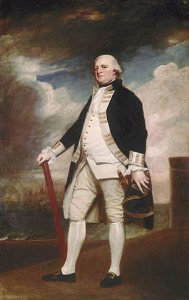

Following his return to Spithead on 21 May after the successful relief of Gibraltar, Vice-Admiral George Darby, the commander-in-chief of the Channel Fleet, was quickly instructed to return to his station in order to protect the valuable British trade in its voyages to and from the home isles.

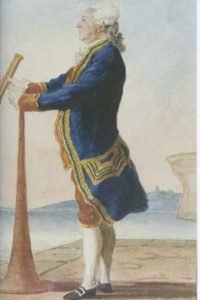

Departing St. Helens on 8 June with as many ships that could be made ready in the short time available, he proceeded towards the Scilly Isles and on the 17th fell in with the Leeward Islands convoy of fifty sail. Having conducted these to safety, Darby sailed south towards Ushant at the beginning of July with twelve sail of the line, these being the Britannia 100, Royal George 100, Queen 90, Duke 90, Formidable 98, Namur 90, Union 90, Edgar 74, Defence 74, Marlborough 74, Inflexible 64, and Medway 60. He was in search of a French squadron of seven sail of the line and four frigates under the command of Admiral Toussaint Guillaume La Motte-Picquet, which was understood to be at sea armed with instructions to raid the British commerce.

After capturing a merchant vessel and an American privateer but failing to find any trace of La Motte-Picquet, Darby was forced to return to Torbay when his fleet was reduced to a mere nine vessels following an outbreak of scurvy and a lack of supplies aboard the Defence, Medway and Marlborough, caused by his earlier rush to sea. Arriving off the Devonian port on 7 July he then made for Spithead where he anchored two days later. In the meantime the homeward bound Jamaican convoy had been met by British frigates and re-routed to safety around Scotland.

There was to be no respite for Darby and his scurvy-ridden ships, for a day after arriving at Spithead the commander-in-chief was ordered back to sea to meet the perceived threat of the Brest fleet of eighteen sail of the line, including four three-deckers, under the command of Vice-Admiral Louis-Urbain de Bou nic, the Comte de Guichen. British intelligence at this time was scant, and it was not known that de Guichen had put to sea with instructions to affect a junction with the Spanish, and to escort an invasion force to Minorca, the French support of the Spanish expedition being somewhat of a sop to their neighbours for the hitherto meagre rewards earned in the conflict. Refined instructions issued on 12 July ordered Darby to escort Rear-Admiral Hon. Robert Digby s North America-bound three sail of the line to a position one hundred and fifty leagues west of the Lizard, and then to seek out de Guichen. Pending his defeat of the French fleet the sailing of all outgoing convoys was postponed.

Contrary winds, coupled with the unavoidable delays in getting his ships provisioned at Spithead, delayed Darby s departure until 19 July, but after collecting further reinforcements at Plymouth he departed the coast with twenty-one sail of the line under his command. This was a far superior force to the one that had struggled back to Spithead at the beginning of the month, and a small measure of success soon attended the fleet when the Perseverance 36, Captain Skeffington Lutwidge, re-captured the Lively 20 from the French on the 29th. After detaching Digby s squadron two days later Darby proceeded to Cape Finisterre, in the vicinity of which he remained for the next couple of weeks.

Then on 17 August Darby received the alarming news from a Portuguese merchantman that an allied fleet of some forty sail of the line and fifty attendant vessels had been seen over two hundred miles to the north, placing them between him and the defenceless English Channel. After counselling his senior subordinates, Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart Ross, Commodore John Elliot, and the captain of the fleet, Richard Kempenfelt, Darby decided to act on the Portuguese information and raced back to enter Torbay on 24 August. During this voyage there was no sign of the enemy, but by then despatches Darby had sent to the Admiralty appraising Lord Sandwich of the allied position had been digested, and the first lord, who had previously received solid evidence that the allies had gone up the Mediterranean, ordered the fleet back to sea once more to protect a home-coming Jamaican convoy, one that was believed to be the most valuable one ever sent.

Darby was in an unenviable position. Although he had received no further intelligence of the allies being in the Atlantic he certainly believed it to be the case, notwithstanding the fact that he erroneously suspected that they had been conducting a convoy from Cadiz into a French port. Contrary to the orders he had been given he therefore decided to make a stand at Torbay, and to form a defensive position off the port. A week passed, during which time Darby sent out his frigates to find the incoming convoys and divert them north around Scotland. One of these, the Juno 32, Captain James Montagu, received intelligence from a Venetian merchantman that the allies were in the Atlantic, and when the Emerald 32, Captain Samuel Marshall, and Prudente 36, Captain Hon. William Waldegrave, spoke with a Swedish merchantman it was established that allies had been seen to the west of the Scilly Isles on 29 August. Final confirmation from a British source arrived with Darby on 1 September in the form of a letter from the commander-in-chief at Plymouth, Vice-Admiral Lord Shuldham, which advised him that Captain Benjamin Caldwell of the Agamemnon 64, sailing with the Quebec convoy, had actually fallen in with the allies some hundred miles to the west of the Lizard on 30 August, and had counted up to forty-seven sail of the line.

Lord Sandwich too had finally begun to receive firm intelligence of the allied movements. It was confirmed that after departing Brest in early July de Guichen had joined with the Admiral Don Luis de Cordova s Spanish fleet of some thirty sail of the line at Cadiz on the 9th. Two weeks later the combined force had sailed through the Straits of Gibraltar to escort an invasion force of ten thousand Spanish troops to Minorca. These were landed on 20 August, and the island eventually surrendered in the following February. The allies, totalling up to forty-nine ships of the line under the command of Cordova, had then gone out into the Atlantic and headed north to the mouth of the Channel with a view to ensuring that no British assistance could be sent to Minorca. They also had the added incentive of intercepting one or two richly laden convoys, and of possibly attacking Cork, where the great North American and West Indian convoy was congregating, Plymouth, Torbay or Portsmouth. The allied fleet was not conveying an army of invasion however, and with this information to hand the Admiralty was able to plan a defence of the Channel without having to take into consideration the factors which had affected Admiral Sir Charles Hardy s defensive campaign of 1779.

Upon the sage advice of the comptroller of the navy, Captain Charles Middleton, Lord Sandwich ordered Darby back to sea to shadow, but not engage, the enemy. The experience gleaned from the 1779 campaign indicated that Darby should wait to take advantage of the inevitable weakening of the Spanish vessels that would be caused by disease, negligence and the weather, and to then attack those ships that became detached. He was advised that he should also look to the defence of Ireland, and to the safe arrival of any homeward-bound convoys. A number of reinforcements had already been added to Darby s fleet, but he was informed that he could not expect any more as the only remaining capital ships in European waters were required on the North Sea station to blockade the Dutch.

Even though he was unable to leave Torbay until 14 September, Darby wasted little time in racing down the Channel the next day, and over the following month he cruised in the Western Approaches, expecting daily to fall in with the allies. By now however sickness, harsh weather and a poor divided leadership had defeated the allies as predicted by Middleton, and they had actually gone their separate ways as early as 5 September. As usual, the allied leadership had been unable to agree on an effective strategy, and time had simply run out on them. On the one hand de Guichen and the Spanish third-in-command, Rear-Admiral Don Vincento Dos, had advocated an attack on the Channel fleet at its defensive position off Torbay in the expectation that a victory would leave Britain vulnerable to any attack the allies chose to make. Contrarily the French second-in-command, Rear-Admiral Antoine Hilarion de Beausset, and the remainder of the Spanish command had demanded that the fleet follow the policy of attacking trade only, rather than undertaking the risk of an extremely dangerous attack upon a moored, static fleet. Eventually, after weeks of achieving nothing as much as the capture of a solitary British vessel, Admiral Cordova had insisted that the fleet return to its home bases. Unsurprisingly when de Guichen entered Brest on September 11 he had to endure the wrath of a country that believed a mortal blow could, and should, have been struck against Britain.

Only on 19 October did Darby receive firm intelligence that the allies had parted company over a month earlier. With the threat of invasion over for another year the Channel fleet was called home, and on 5 November it anchored at Spithead, somewhat worn out but still in being. Once again the calm, dignified and understated Admiral Darby had done well.

Channel Fleet which sailed from Portsmouth on 21 July:

| Britannia 100 | Vice-Admiral George Darby |

| Captain of the Fleet Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt | |

| Captain James Bradby | |

| Royal George 100 | Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart-Ross |

| Captain John Bourmaster | |

| Edgar 74 | Commodore John Elliott |

| Captain Thomas Boston | |

| Victory 100 | Captain John Howorth |

| Union 90 | Captain John Dalrymple |

| Queen 90 | Captain Hon. Frederick Lewis Maitland |

| Duke 90 | Captain Sir Charles Douglas |

| Formidable 98 | Captain John Cleland |

| Namur 90 | Captain Herbert Sawyer |

| Ocean 90 | Captain George Ourry |

| Foudroyant 80 | Captain John Jervis |

| Valiant 74 | Captain Samuel Granston Goodall |

| Cumberland 74 | Captain Joseph Peyton |

| Defence 74 | Captain James Cranston |

| Courageux 74 | Captain Lord Mulgrave |

| Alexander 74 | Captain Lord Longford |

| Repulse 64 | Captain Sir Digby Dent |

| Inflexible 64 | Captain Rowland Cotton |

| Emerald 32 | Captain Samuel Marshall |

| Ambuscade 32 | Captain Hon. Hugh Seymour Conway |

| Alarm 32 | Captain Charles Cotton |

| Crocodile 24 | Captain James King |

| Narcissus 24 | Captain Edward Edwards |

| Zebra 16 | Captain John Bourchier |

On 24 August the fleet sailed into Torbay, having been joined by the following ships:

| Marlborough 74 | Captain Taylor Penny |

| Arrogant 74 | Captain Samuel Pitchford Cornish |

| Conqueror 74 | Captain George Balfour |

| Hercules 74 | Captain John Brisbane |

| Medway 60 | Captain Harry Harmood |

Further additions to fleet as at 10 September 1781:

| Dublin 74 | Captain Archibald Dickson |

| Prothee 64 | Captain Charles Buckner |

| Nonsuch 64 | Captain Sir James Wallace |

| Agamemnon 64 | Captain Benjamin Caldwell |