The Navy’s role in Lord Macartney’s Embassy to China – 1792-4

For many years there had been frustration in mercantile circles, in particular within the East India Company, at the restrictions placed on British trade by the Chinese authorities, and in government circles at the huge disparity in commercial receipts between the two countries. Amongst many gripes held by the former was the stipulation that foreign merchant ships could only dock at the port of Canton, the modern-day Guangzhou, thereby depriving them of the opportunity of opening new markets, whilst for the latter the biggest concern was that the home market’s desire for tea and silk far outweighed any Chinese demand for British products.

In 1787 William Pitt’s government had attempted to lobby the Chinese Emperor over these issues by despatching Colonel Hon. Charles Cathcart aboard the frigate Vestal 28, Captain Sir Richard John Strachan, to take up the position of ambassador. Unfortunately the diplomat had died in the Straits of Banca during the outward voyage before he could take up his post, and it was not until 1791 that the influential home secretary Henry Dundas nominated the experienced 54 year-old diplomat and politician Lord Macartney to undertake the mission originally designated to Cathcart. The former governor of Grenada and Madras accepted the offer early in 1792 with the provision that before the mission set sail he should be raised to an earldom.

Anxious lest he share Cathcart’s fate and perish before reaching China, Macartney obtained the services of an able deputy in the shape of his long-term associate, Sir George Staunton, whilst amongst up to a hundred other worthies who became attached to the expedition were interpreters, doctors, scientists, botanists, artists and academics. The mission itself would be chiefly financed by the East India Company, which of course stood to benefit greatly from a successful conclusion.

At Lord Macartney’s behest, the esteemed Captain Erasmus Gower, a double circumnavigator in his embryonic career and a renowned seaman, geographer, and astronomer, was appointed to the Lion 64 which would carry the embassy to Peking, and in turn Gower was allowed to select his own officers for the mission. Such an auspicious voyage was sure to guarantee a lot of interest, and soon Gower was inundated with requests from anxious parents seeking berths for their sons in the gunroom, with the result that a vast number of midshipmen, far in excess of the prescribed complement, were accepted aboard. These included the future Admiral John Thompson, Vice-Admirals Lord Mark Robert Kerr and Frederick Warren, and Captains Lord William Stuart, Charles Dilkes, Edmund Heywood and Sir Philip Silvester. In addition, the future Captain David Atkins and Admiral Sir John Acworth Ommanney would serve on the Lion as the third and an acting-lieutenant respectively.

A naval tender, the ex-Welsh coasting vessel Jackall, was ordered to accompany the Lion on the expedition, and she was placed under the command of a masters’ mate, James Sanders, with a crew of nine hands. A third vessel was also attached to the mission, this being the East Indiaman Hindostan, Captain William Mackintosh, and soon her deck seams were bulging with the gifts and samples of British products that were stowed below for eventual delivery to the Chinese Emperor. She would also give passage to any of the ambassador’s retinue who could not find a berth upon the Lion.

On 1 August Captain Gower kissed hands with the King and was knighted at a levee attended by Macartney and Staunton, and amidst much public excitement the three ships finally departed Portsmouth on 26 September. Almost immediately they ran into adverse winds and heavy weather, and on the night of the 28th the Jackall parted company off Portland. Nevertheless, Sanders persisted on his course, and despite encountering further unfavourable conditions he reached Madeira on 22 October, only to find that the Lion and Hindostan had arrived off the islands on 10 October but had left on the 18th. Fortunately, an anxious Captain Gower had left instructions to the effect that Sanders should seek him out at the Cape Verde Islands, and if he was no longer there, should rendezvous off North Island in the Straits of Banca on the far side of the world.

After leaving Madeira, where Macartney had been entertained by the Portuguese governor and the British consul, and where a reciprocal visit to the Lion had been arranged for the island’s notability, Gower had steered for Tenerife in the Canary Islands where the Lion and Hindostan anchored in Santa Cruz Bay on 21 October. Three days later a party of adventurers set out in the early hours to attempt the ascent of Mount Teide, which was then considered to be one of the highest mountains in the world by European travellers, but after barely making the foothills that evening they abandoned the enterprise the next day to walk back to Santa Cruz, where on the 27th the mission put to sea once more and set a course for the Cape Verde Islands, which they reached on 2 November.

Back at Madeira, the Jackall’s initial departure from Funchal had been more precipitate than intended, for a storm forced her to slip her cable and run out to sea, and thereafter she thrashed to and fro for the better part of a week before the wind veered around and enabled Sanders to regain the Funchal Roads. Her anchor recovered, the Jackall set sail again on 30 October, reaching Porto Praya in the Cape Verde Islands eleven days later only to find that the Lion and Hindostan had left that port two days previously. Even worse for Sanders was the fact that drought and famine had afflicted the island so badly that he was barely able to provision his ship, and this was much to the mortification of his small crew who took a great deal of persuasion to continue with the voyage to the Straits of Banca.

Some way out in the Atlantic Ocean the Lion and Hindostan traversed the equator on 18 November and two weeks later came to anchor at Rio de Janeiro. Here, accompanied by much reciprocal civility between the Portuguese viceroy and the mission’s elite, the ships were furnished with enough wood, water and provisions to obviate any requirement for stopping at the Cape. Weighing anchor on 18 December, they came in sight of the Tristan da Cunah islands in the Southern Atlantic, some fifteen hundred miles west of the Cape, on New Year’s Eve, but a plan to explore the interior was abandoned when a gale drove the Lion out to sea. Thereafter the two ships raced along in inclement weather and passed the Cape on 7 January, but with the Lion suffering storm damage they were compelled to anchor off the barren island of Amsterdam in the Indian Ocean on 1st February to effect repairs. Here they found a small party of men, two English, two American and their French leader, who were engaged on a fifteen-month seal cull to provide skins for the extremely lucrative Chinese market. It appeared to be a good omen.

As the long voyage across the Indian Ocean continued the crews and passengers on board the Lion and Hindostan unsurprisingly began to show signs of debility and disease, and this became a greater issue when on 6 March the two ships reached Batavia. Gower was well aware of the Dutch staging post’s unhealthy climate and having not lost a single man out of the six hundred under his care he was determined not to tarry any longer than the time it took to re-provision, and to purchase a second brig to replace the missing Jackall. The latter objective was soon satisfied, with the new vessel being named the Clarence in honour of Prince William, the Duke of Clarence, but with the ambassador and his suite taking lodgings ashore in the Royal Batavian Hotel, and then Lord Macartney falling ill with gout, the ships were still at Batavia when the Jackall reappeared on 23 March, almost six months since parting company and four months since leaving Porto Praya. Somewhat fortuitously she had only encountered one storm on her passage, this to the east of Madagascar, and although her crew had been on short provisions for weeks, she was otherwise in good order.

Sadly, within days of the four ships leaving the stagnant, unhealthy coasts of the Dutch East Indies, three men from the Hindostan succumbed to disease, and then two more lives were lost when one man apparently fell overboard in his sleep, and another by the name of Leighton was murdered on Sumatra by a native. It was now the tail-end of the monsoon season and the crews had to battle thunderstorms and violent gusts of wind, combined with appalling heat that brought about horrendous conditions below decks. Soon over one hundred men out of the three hundred and fifty aboard were on the Lion’s sick list, and as the various diseases began to take their toll some twenty would lose their lives in the succeeding weeks, including the purser and the gunner.

By 18 April the ships were finally clear of the shallow and tricky Straits of Sunda between Java and Sumatra, and on 8 May they fought their way through the equally perilous Straits of Banca between Sumatra and the island of Banca. Continuing on a north-westerly track, Gower’s hope of replenishing provisions was thwarted by ill-winds and timid islanders, but by 18 May the mission was off the coast of Cochin China, or modern-day southern Vietnam, and eight days later it anchored in Turon Bay, the latter-day port of Da Nang. Here the local king, a thirteen-year-old boy, proved amenable and during a three-week stay hope were raised of the possibility of establishing a trading post called New Gibraltar. Unfortunately, these did not come to fruition, and matters almost took a turn for the worse when on 7 June the sailing master of the Lion and his boat crew of seven men were seized whilst sounding in the bay amidst local suspicion that they were spying on the coastline. Negotiations were undertaken and the men were released six days later, but not without great concern for their well-being, coupled with a fear that their transgression against a client kingdom of the Chinese Empire might have unfortunate repercussions.

With the climate in Turon Bay initially proving beneficial, Gower had sent ninety men ashore to recover their health, and although he had to re-embark them four days later when the heat returned this break did the trick and the hands were restored to good health in time for the change of season that saw the mission sail north to anchor off the Great Ladrone to the south of Macau on 22 June. Two days later the ships entered the modern-day Taiwan Strait between China and Formosa, where they at first experienced favourable weather before enduring ferocious thunderstorms towards the end of their passage.

At the beginning of July, the ships reached the port of Chusan, the modern-day Zhoushan, and here they found it necessary to seek pilots before entering the Yellow Sea and the Gulf of Peking, as these waters were alien to European navigators. It soon became clear that navigating large ships in more than six feet of water was alien to the local pilots too, but the East India brig Endeavour was on hand to help, and upon leaving Chusan on 9 July a worrisome, vigilant, tedious voyage ensued in which the fevers returned with a vengeance, with up to eighty men on the sick list at any time and deaths occurring every four or five days. Not until 25 July did the mission come to anchor, some fifteen miles from Tientsin, the modern-day Tianjin, and here Lord Macartney and his entourage embarked into the Jackall, Clarence and Endeavour to proceed upriver to Dagu whilst the cargo of gifts and sample products was loaded onto junks to make the same journey.

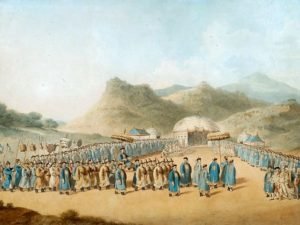

At first the Chinese could not have been more welcoming. Boatloads of bullocks, sheep and hogs were delivered to the ships, senior mandarins attended the ambassador, and various houses were prepared for his entourage when on 5 August it began the one-hundred-and-thirty-mile journey up to Peking. Nonetheless the Chinese remained circumspect of their visitors, and upon reaching the city on 21 August the British delegation remained confined in its residence until 2 September, when up to seventy members were allowed to commence the one-hundred-and-forty-mile journey up to Rehe, the modern-day Chengde. It was here that the Chinese emperor, Tehien Lung, otherwise known as Qianlong, warily and most imperiously awaited them.

On 14 September the two parties finally met at a ceremony witnessed by several thousand attendees and having previously negotiated an opt out to making the traditional kow-tow before the emperor Macartney instead knelt and presented Tehien Lung with a letter from King George III. Yet as negotiations began it soon became clear that despite the generosity of their gifts and their eagerness to trade the British would leave empty-handed. Requests for access to more Chinese ports, for the provision of an island off the coast where a British factory could be established, for a commercial treaty, for a permanent embassy – all were denied, and in a haughty letter of response to King George the emperor declared that his country was blessed with all the products it required and had no need to trade with barbarian outsiders. The final insult came when after disdainfully inspecting the gifts bestowed on him throughout the first two weeks of October the emperor suddenly, and without any ceremony or display of good grace, declared that the mission should be on its way.

Back off the coast, Captain Gower had anxiously sought a safe anchorage for the Lion and Hindostan and a haven ashore for his sick men. Sailing south from Tientsin, he had found nothing that would accommodate any vessel larger than a Chinese junk until reaching Chusan, a voyage of some nine hundred miles. Here he remained for some weeks, although his men rarely ventured ashore as the emperor had sent instructions for the sickly ships to be quarantined. By the end of October, the two vessels had worked some further nine hundred miles to the south and were off Macau to take on supplies, particularly medicinal. From here in December, they ran the short distance up to Whampoa to meet the ambassador who ultimately arrived there on 8 January after being conducted south from Peking over three months in a succession of junk voyages and overland journeys.

Following a two month stay at Macao the Lion left Chinese waters on 17 March 1794 with a convoy of Indiaman, the Hindostan having departed earlier, and after collecting further merchantmen at Bengal she reached St. Helena on 19 June. Here she was joined by the Argo 44, Captain William Clarke, and the Sampson 64, Captain Robert Montagu, and the extended convoy departed that island on 1 July to anchor at Spithead on 3 September, nearly two years since setting out, whereupon the Lion was sent around to Chatham to be paid off.

Although the mission had failed in all of its prime objectives, this being attributed to an apparent inherent Chinese jealously of the Europeans and in particular of the British, it was nevertheless deemed a success for the knowledge that had been gleaned of the Chinese Empire. On a personal level it was certainly a success for Mr Sanders who received great credit for his efforts in independently reaching the far side of the world in such a tiny vessel as the Jackall, and upon his return to England he received his lieutenant’s commission following Lord Macartney’s strong recommendation.

As for Captain Gower, he had already been rewarded with a knighthood prior to the mission’s departure, and all that was left for him to do was to count the personal cost of having entertained Lord Macartney and his retinue for the best part of two years with no prospect of reimbursement. At least that cost was somewhat offset by the generous reward he received from the East India Company for seeing their convoy safely home.