RICHARD HOWE 1ST EARL 4TH VISCOUNT

1726-99. He was born on 8 March 1726 in Albemarle Street, London, the second son of Emanuel Scrope, 2nd Viscount Howe of Langar, Nottinghamshire, in the Irish peerage, and Maria Sophia Charlotte, daughter of the Baron and Baroness Kielmansegge who came to London from Hanover on the succession of the baroness’s half-brother to the English throne as King George I. One of ten children, Richard Howe was the brother of General Hon. Sir William Howe 1729-1814, and General Hon George Augustus, the 3rd Viscount Howe 1724-1758.

In 1732, at the time that his father was the governor of Barbados, Howe enrolled at Westminster School, and he was educated under the headmaster, John Nicholl, whose future pupils included Edward Gibbon, Warren Hastings, William Cowper and Sir William Hamilton. Three years later, in the same year that his father died, he moved to Eton, whilst it has also been stated that he served in the merchant marine from 1736-9.

On 16 July 1739 he joined the Pearl 40, Captain Hon. Edward Legge, serving off Portugal, and he then moved to the Severn 50 with Captain Legge in Anson’s planned circumnavigation of the globe, although this ship had to return to England when she failed to weather Cape Horn. On 17 August 1742 he joined the Burford 70, Captain Franklin Lushington, serving in the West Indies, and he first came to public notice when he burst into tears whilst describing to a court martial the death of his captain in battle at Caracas on 22 February 1743. In March he joined the Suffolk 70, Captain Edward Pratten, flying the broad pennant of Commodore Charles Knowles, progressing on 10 July to acting-lieutenant of the Eltham 40, Acting-Captain Richard Watkins, before returning to the Suffolk with his old rank of midshipman in October.

On 25 May 1744 he was commissioned lieutenant by Commodore Knowles, a promotion that was confirmed by the Admiralty on 8 August 1745, and he joined the fireship Comet, Commander Richard Spry, in which he returned to England to be paid off in August 1745,whereupon he was appointed on 12 August to the Royal George 100, Captain Thomas Harrison, flying the flag of Admiral Edward Vernon in the Downs.

On 5 November 1745 he was promoted commander of the sloop Baltimore 14, arriving at Greenock from Ireland in February 1746 to serve against the Jacobites and assist in the defence of Fort William during the siege of 20 March to 3 April. On 2 May, and following the defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden, the Baltimore in company with the frigate Greyhound 20, Captain Thomas Noel, and the sloop Terror, Commander Robert Duff, engaged two superior French privateers which were landing arms for the Young Pretender’s desperate supporters in Loch nan Uamh on the west coast of Scotland. The action lasted for some five hours in front of hundreds of spectators who were hoping to plunder the landed cargo, and the French in particular suffered many casualties, although Howe himself sustained a severe wound to the head. Eventually the smaller British vessels, being badly damaged aloft, had to withdraw in order to effect repairs in Aros Bay, and having sought reinforcements they sailed to renew the engagement but found that the French ships had left the area.

Howe was posted captain of the Triton 20 with seniority from 10 April 1746 (see footnote) and he returned to England, however in the same month the Triton sailed for Scotland under the command of Captain Peircey Brett, who retained her for the next few months. Upon joining the Triton, Howe was later ordered to convey the trade to Portugal, embark treasure at Lisbon, and return it to England, but on arriving in the Tagus some time after April 1747 he transferred to the Rippon 60 in place of Captain Francis Holburne who was unwell. With his commission to the Rippon being approved in September, Howe sailed for the Guinea coast under the orders of Captain Ormond Tomson of the Poole 44, and from thence to the West Indies. At Jamaica on 29 October 1748 he became the flag captain to Rear-Admiral Charles Knowles aboard the Cornwall 80, and he returned with that ship to England at the end of the War of Jenkins’ Ear, arriving at Spithead in June 1749 and being paid off in the following month.

Howe commissioned the new Glory 44 in March 1751, going out to West Africa in May as commander-in-chief, voyaging to the West Indies, and then returning on 22 April 1752 to England, whereupon he assumed the command of the yacht Mary, an honorary position which he held until the following summer. On 3 June 1752 he commissioned the new frigate Dolphin 20, sailing for the Mediterranean from Spithead in September having been wind-bound for several weeks, but then putting into Plymouth before resuming his voyage towards the end of October. In the summer of 1753 he was entrusted with a diplomatic mission to the Barbary Coast prior to returning to Portsmouth via Lisbon in July 1754, whereupon he left the Dolphin.

In January 1755 he was appointed to another new vessel, the Dunkirk 60, which he fitted out and manned at Chatham without the need for accepting any pressed men. With hostilities considered to be imminent against France as a consequence of the proxy French and Indian War in North America, he was ordered around to Spithead where he arrived from the Downs on 14 April. He then joined the fleet destined for North America under Vice-Admiral Hon. Edward Boscawen which sailed from Plymouth in May. His seizure of the unprepared Alcide 64 in the St. Lawrence on 8 June with the assistance of the Torbay 74, Captain Charles Colby, was a key factor in the opening of the Seven Years War which would officially commence in the following May; however the initial reports printed on 15 July back in England erroneously claimed Howe’s death with ninety of his crew in a brutal engagement. The fleet departed Halifax on 19 October to arrive at St. Helens on 14 November where orders had already been given to refit the ships without delay

At the end of the year the Dunkirk was at Plymouth, and in March 1756 she sailed out under the orders of Rear-Admiral Savage Mostyn to join Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Hawke off the port. Shortly afterwards the Dunkirk and the Medway 60, Captain Peter Denis, sent two captured vessels from Martinique into Portsmouth, and at the beginning of May she arrived at Spithead with Hawke’s flagship and four other vessels before going into dock on the 30th. So pleased was Howe with the promptness of the artificers in replacing his fore and main masts that he gave them two guineas to drink to his health.

In June 1756 he raised a broad pennant in order to lead a small squadron of seven men-of-war in the defence of the Channel Islands, and in this capacity he captured the Ile de Batz off Morlaix, together with four transports carrying troops, and later in July took control of the Chausey Islands off Granville without bloodshed. Having destroyed all the buildings and brought off the cattle and copious quantities of wine and brandy the Dunkirk returned to Plymouth on 8 September from where she sailed out in November with Vice-Admiral Knowles for the Bay of Biscay. During February 1757 Howe sent the small privateer Prince de Soubize into Portsmouth, and shortly afterwards he accepted the hospitality of the Spanish at Ferrol to repair storm damage to his command.

In April 1757 the Dunkirk was at Spithead, and on 5 May she left Portsmouth to escort half a dozen Indiamen out of the Channel, being in the company of the Lancaster 66, Captain George Edgcombe. She then embarked on a cruise during which she captured the Bordeaux privateer Nouvelle Saxonne 16 on 28 May, and then assisted the Lancaster in the capture of the Bayonne privateer Comte de Gramont 36 on 9 June. The two vessels with their prizes arrived back at Plymouth on 18 June. In the meantime, during May, Howe had been elected M.P. for Dartmouth in the Government interest, and this was a seat that he would hold for the next twenty-five years.

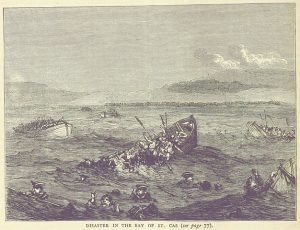

The Disastrous embarkation of the Army at St. Cast in 1757 could have been much worse but for Howe’s leadership.

On 2 July 1757 he transferred with his crew to the Magnanime 74, although his new command spent most of that month in dock at Portsmouth, prior to joining the grand fleet under Admiral Sir Edward Hawke on 1 August. In early September the fleet put to sea, and during the attack on Rochefort on 23 September Howe not only led the line but in a thirty-five minute bombardment silenced the Aix batteries after reserving his fire until coming to at point-blank range beneath their walls. During this action the Magnanime lost two soldiers killed and eleven men wounded, whilst also suffering material damage aloft. The fleet returned to Portsmouth on 1 October, and two weeks later Howe was summoned to London by express before returning to Portsmouth and taking the Magnanime out to sea at the end of the month to rejoin Hawke. Shortly afterwards his command in company with the Tartar 24, Captain John Lockhart, captured two French vessels from Saint Domingue.

In April 1758 the Magnanime was ordered out of Plymouth to head for Portsmouth, from where she sailed for the Bay of Biscay to join Hawke once more. During June-July, whilst Captain Jervis Porter assumed temporary command of the Magnanime, Howe raised a broad pennant aboard the Essex 64, Captain Richard Dorrill, and in command of some one hundred and fifty vessels including 50-gun ships and frigates sailed on 1 June to raid the French Coast in co-operation with the Army led by the Duke of Marlborough and Lord George Sackville, the future Lord Germain. Landing some five thousand troops in Cancale Bay on the 6th, an attack against St. Malo was largely unproductive despite a minimal enemy resistance as the defences of the town were considered too substantial to withstand anything but a long siege. Nevertheless over a hundred vessels and the dockyard facilities were destroyed, although any plundering by the soldiers and seamen was harshly punished, and those French citizens who did flee on the British approach were recalled with assurances as to their safety.

Once the troops had been re-embarked the fleet was obliged to ride out a gale in Cancale Bay, and when Howe and the Duke of Marlborough reconnoitred the port of Granville it was decided that an attack there was unfeasible. On 2 July the expedition briefly returned to Portsmouth where the horses were put out to grass and Howe went up to London for consultations, arriving in town on the 5th. Four days later he was back at Portsmouth where the fleet was being rapidly re-provisioned, and with bombardiers and siege equipment being taken aboard the squadron dropped down to St. Helens on 27 July.

Returning to the coast of France, and with Lieutenant-General Thomas Bligh having taken command of the army, the port of Cherbourg was next targeted with an attack by bomb vessels on 6 August after the residents had been warned to leave their homes. The troops were landed in Marais Bay the next day under covering fire of the frigates and smaller vessels, and a force of some three thousand regular French troops were put to flight before possession of the town was completed on the 8th. Again the commanders-in-chief ensured good order by insisting that the shops be kept open and all goods be paid for, and by the 16th all the troops had been re-embarked after reducing the port to a mere ruin and destroying all the vessels therein. Such was the effectiveness of this devastation that the facilities in Cherbourg would not be usable for another thirty years.

At the end of August the fleet was driven back across the Channel to the Portland Roads by contrary winds, but by 4 September it was in the Bay of St. Lunaire off Brittany, from where the troops were landed to attempt another attack on St. Malo. Again it was decided that the formidable defences could not be breached within a safe timeframe, and when poor weather closed in and it became known that French forces were on the march it was decided that other than destroy some twenty ships and coastal batteries all that could be done was for the army to be re-embarked. Accordingly the fleet moved around to St. Cast Bay towards the west. What followed was a disaster, for when the embarkation commenced on the morning of the 11th it was disrupted by the unexpectedly early arrival on the beach of the French, and in the mayhem that followed some eleven hundred men were killed or wounded and seven hundred taken prisoner, including Captains Joshua Rowley, Jervis Maplesden and William Paston, and Commander John Elphinstone, who had all been fighting with the rear-guard. The loss could well have been greater if not for Howe’s bravery and leadership, but such was the scale of the defeat that it was decided to abandon all such further so-called ‘descents’ on the coast of France and the fleet returned to Portsmouth.

Meanwhile news had come through that on the death of his elder brother, George Augustus, at the siege of Ticonderoga on 5 July Howe had become the 4th Viscount Howe in the Irish Peerage. At the beginning of October he rejoined the Magnanime and sailed for the Bay of Biscay to serve under Rear-Admiral Charles Saunders, prior to returning to Portsmouth on Christmas Eve. On 13 April 1760 the Magnanime sailed from Spithead for the Bay with Vice-Admiral Hon. Edward Boscawen’s squadron, but Howe was back in England at the end of the month, whereupon he set off for London with the expectation that he would command another raiding expedition on the French coast. In the event this did not transpire, and weeks later the Magnanime was attached to Admiral Sir Edward Hawke’s fleet which was stationed off Ushant, yet which regularly took the opportunity to parade off Brest in order to show the flag. During June Howe’s command cruised with a small squadron under Commodore Hon. Augustus Keppel of the Torbay 74, and she returned to Plymouth on 1 October before going out once more to join Hawke’s grand fleet.

On 20 November 1759 the Magnanime with four other vessels led Hawke’s fleet into the Battle of Quiberon Bay, and Howe earned great praise for this bold and professional approach into what were dangerous waters. His assault on the Héros 74, sailing to within pistol shot before opening fire, caused one French survivor to comment that he had been involved in a massacre rather than an engagement. The Magnanime was then largely instrumental in the sinking of the Thésée 74. Following the battle Howe was sent ashore to claim prisoners who had absconded from the Héros after her surrender, and he was received with military honours and lavishly entertained by the defeated French. The Magnanime returned to St. Helens on Christmas Day, but her arrival was less than glorious, for she became stranded for several hours on Bambridge Ledge prior to getting off the following morning. Howe set off for London two days later where he immediately attended the King, whilst his crew, which included a large contingent of Irishmen, were given fourteen days leave of absence in January 1760 at his request, which was then extended for another fourteen days. As a personal reward for his many achievements Howe was appointed a colonel of marines on 4 February 1760.

He was absent on leave when the Magnanime sailed for Quiberon Bay in May 1760, his temporary replacement being Captain Robert Hughes who remained in command until Howe set sail from Portsmouth aboard the Modeste 64, Captain Henry Speke, to join his ship in Quiberon at the end of July. Continuing on this station, he captured the island of Dumet with three sail of the line on 4 September, but after returning to Portsmouth at the end of October he was superficially wounded with a contusion to his side some weeks later when a smoke bomb prematurely exploded whilst he was observing its trials at Woolwich.

In January 1761 it was reported that Howe was indisposed and that Captain Thomas Lynn would act for him in command of the Magnanime, and with rumours that he would command another expedition proving unfounded he was eventually ordered to go aboard his command in July and sail with all the ships available to join Commodore Keppel in the Bay of Biscay. The Magnanime was back at Portsmouth by September from where she sailed once more for the Bay on the 7th. On 6 February 1762 Howe arrived at Plymouth to hoist his broad pennant aboard the Magnanime with Charles Saxton acting as his flag-captain, and at the end of February sailed for the Basque Roads to replace Commodore Sir Thomas Stanhope with a squadron of ten sail of the line, two frigates and two fire-ships. The Magnanine was back at Portsmouth in early May whereupon Howe left her. He subsequently undertook a largely symbolic role as flag captain to Rear-Admiral Prince Edward Augustus, the Duke of York, aboard the Princess Amelia 80 from June 1762, sailing with a fleet under Admiral Sir Edward Hawke for Lisbon and returning to his house in Whitehall, London at the beginning of September, at which point his service in the Seven Years War came to an end.

In April 1763 Howe was appointed a lord of the Admiralty under Lord Sandwich in George Grenville’s new Whig government, on 26 July 1765 he joined the privy council, and in August of that year he became the treasurer of the navy, a potentially lucrative post which in his true honest fashion he failed to make the best use of. He resigned as a lord of the Admiralty in May 1766 and for several years took the opportunity to enjoy more leisurely pursuits, as in August 1768 when he visited the Hot Wells in Bristol.

In 1770 he left his post as treasurer of the navy on the replacement of the Duke of Grafton’s Whig administration with that of Lord North’s Tory government, and on 18 October he was advanced to the rank of rear-admiral, the promotion being extended to include him. On account of the disagreement with Spain over the Falkland Islands he was appointed commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean towards the end of November, and his flag was raised at Chatham aboard the Barfleur 98, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond. In January 1771 this vessel went into dock for sheathing prior to putting to sea, but in the event the dispute with Spain was settled and by February he had resigned his position having never taken left the country.

During the next few years of peace Howe continued to move in the highest circles, as in March 1772 when he attended a conference at Buckingham Palace with Admiral Sir Edward Hawke and Vice-Admirals Hon. Augustus Keppel and Sir Peircey Brett to discuss the possibility of sending a fleet against Denmark after the queen of that country, King George III’s sister, had been arrested by her erstwhile husband King Christian VII. When ships were believed to be re-commissioning at Portsmouth and Chatham in April it was advanced that Howe would lead a fleet to be sent to Copenhagen, but in the event this proved to be nothing more than speculation, as were the reports in October that he would command a squadron of observation off France and Spain. In the meantime he remained active in political matters, as in February 1773 when he brought a motion to the House of Commons advocating an increase in captain’s half-pay.

As early as August 1775 it was reported that Howe was to have the chief command in North America as he was known to be on good terms with the rebellious colonies, and in particular Benjamin Franklin, whom he admired greatly and thought would be willing to negotiate. Having been promoted vice-admiral on 3 February 1776 he was officially appointed commander-in-chief and he left Spithead on 12 May to sail firstly to Boston, thence to Halifax, and finally to join his brother, General Sir William Howe, at New York on 12 July. In the interim the two Howes had been appointed peace commissioners on 3 May with the expectation that they would reach a conciliatory arrangement with the rebels, but by the time they met with the Congress in September the Declaration of Independence had already been announced, and they were unable to achieve a breakthrough. Concluding that further negotiations were pointless in the face of sheer belligerence the Howes were thereby obliged to take the war to the Americans.

The fleet in North America consisted of the flagship Eagle 64, Captain Henry Duncan, and some 50 gun ships but no 74’s as Lord Sandwich at the Admiralty was wary of a French attack at home. Furious that governmental interference had diverted a strong squadron under Commodore Sir Peter Parker and four thousand troops commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton to make an ultimately futile attack on the port of Charleston on 28 June 1776, Howe nevertheless co-operated successfully with his brother in the reduction of Long Island and New York campaign from July-October, in the course of which his flagship survived a novel submersible attack on 6 September. During the following winter he displayed the intractable, scrupulous side of his character in dealing with a degree of insubordination from the Rhode Island based captains over the court-martial of Lieutenant John Duckworth, who had negligently caused the deaths of five men on 18 January 1777. That summer, with Captain Roger Curtis having become his flag-captain at the end of April and Duncan his captain of the fleet, he conveyed his brother’s army to the Head of the Elk, disembarking on 25 August and returning to the Delaware to command the clearance of that waterway. Philadelphia was then captured by his brother and the Delaware River was opened up to the sea, but on hearing that a superior French fleet was crossing the Atlantic Howe took the larger of his vessels back to New York in December, and Philadelphia was evacuated in the following June.

In the meantime a new peace committee had been set up and Howe along with his brother tendered his resignation on 23 November 1777, bitter at have been seemingly deposed and having not enjoyed support from the government. The resignations were accepted on 24 February 1778, but with the caveat that the Admiralty hoped Howe would no longer feel resignation necessary. Before his replacement could be effected his brilliant dispositions and powers of leadership repelled the Comte d Estaing s fleet of twice his number off Sandy Hook in July. When the French sailed for Rhode Island he followed them, arriving on 9 August but refusing to give battle as he did not want to fight on his enemy s terms. A violent gale dispersed the fleets but not before Howe s 50-gun ships harried d Estaing s bigger ships back to Boston. After returning to Sandy Hook Howe went back to Boston on 31 August but by now the French fleet was in total disarray and it was with some satisfaction that he was able to leave America on 25 September. After avoiding three French sail of the line in the Channel the Eagle arrived at Portsmouth on 25 October and Howe struck his flag five days later.

Admiral Lord Howe

For the next three years he lived at Porters Lodge, near St. Albans, whilst he and his brother defended themselves against claims that they had not prosecuted the war to the best of their abilities. Howe refused to serve without the removal of both Sandwich from the Admiralty and of Lord Germain who was by now the secretary of state for the colonies, even turning down the opportunity to replace Admiral Hon. Augustus Keppel in command of the grand fleet. The King considered the possibility of his favourite admiral replacing Lord Sandwich in order to unify the fleet following the fallout from the Battle of Ushant on 27 July 1778, but Howe would not countenance it without the approval of his North American campaign, his elevation to the British peerage, and the discussion of the withdrawal of offensive forces from North America. In February 1779 a meeting with the prime minister Lord North took place following the King s authorisation that Howe could be approached, but on the 19th Howe seconded Admiral Hugh Pigot in a motion demanding that the King dismiss the government s man in the Battle of Ushant dispute, Vice-Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser, and from then on he largely supported the Whig opposition. Between January and July there was much debate in the Houses of Parliament over the Howes North American campaign, and in a speech he made on 8 March Howe accused the government of distributing false pamphlets denigrating him and his brother. Without a doubt the administration considered the Howes to be excellent and convenient scapegoats. After reiterating that he had wanted to leave the post of commander-in-chief earlier but could not do so with the French aboard, Howe demanded an enquiry into his conduct. The most determined of his opponents was the ridiculous Commodore George Johnstone, who stated that Lord Howe s conduct at New York was worthy of reproach. Howe thereafter largely remained silent and rejected several attempts by Catherine the Great to enlist him into the Russian service. In addition to his professional concerns he also had personal reasons for despising the Lord North administration, having been promised the position of lieutenant-general of the marines by the prime minister in 1775, only for North to forget and award the role to Sir Hugh Palliser. Additionally he had been promised the position of treasurer of the navy in 1777, but it was found that this could not be offered such a post whilst he was serving in North America.

Following the eventual resignation of Lord North’s administration Lord Howe was appointed commander-in-chief in the Channel on 2 April 1782, which post, together with the conferring of the position of Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance on his brother, was his price for returning to service. On 8 April he was promoted admiral of the blue, and he hoisted his flag on the 20th at Spithead aboard the Victory 100, Captain Henry Duncan, and with Commodore John Leveson-Gower as captain of the fleet. On the same day he was elevated to the House of Lords as Viscount Howe of Langar in the English peerage.

During the Channel fleet s April – August campaign he sailed to the Texel in May with a division of the fleet to watch over the Dutch fleet, thereafter joining Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt off Brest. When news came through in July that the Franco/Spanish fleet of thirty-two ships had come out of Cadiz and taken the Newfoundland convoy he left the Texel in order to defend the expected Jamaica convoy, which he successfully brought in after skilfully avoiding the allies near the Scilly Isles, their strength having risen to thirty-six as opposed to his twenty-five. He arrived back at Spithead on 14 August to refit but on the 29th lost the Royal George, which sunk with great loss of life including that of the brilliant Kempenfelt, and this double catastrophe meant that with few enough ships already to prosecute his intentions, he was under extreme pressure.

On 11 September he sailed to relieve Gibraltar with thirty-four ships-of-the-line and a convoy of one hundred and thirty-seven vessels. The passage was very slow and it was not until 8 October that he was off Cape St. Vincent. Gibraltar was relieved on 18 October and after a minor action off Cape Spartel the allied fleet of forty-eight sail withdrew to Cadiz. Thus when Howe returned to St. Helens on 14 November it was to a hero s welcome celebrating his brilliant strategy, and he received a hand-written letter from the King of Prussia himself, praising his conduct. Even so, on 20 October he felt obliged to challenge Lord Hervey of the Raisonnable 64 to a duel after this officer had taken exception to some perceived sleight and had stated that the fleet could have destroyed the allies if had been led properly. Sensibly Hervey apologised when the two men met at the ground.

After the peace in 1783 Howe became the first lord of the admiralty in the Earl of Shelburne’s Whig administration, serving from 28 January until the Fox/North government assumed power on 16 April, and then from 31 December 1783 until July 1788 under William Pitt’s Tory administration. Amongst his varied duties he personally intervened in March 1783 to prevent a mutiny aboard the frigate Janus 44, Captain William Henry King O’Hara, which had been ordered to sail for North America by his predecessor when the war-weary crew were expecting to be paid off. In May 1788 he demanded the dismissal of Captain Isaac Coffin following this officer s court-martial for keeping false musters, but the verdict was overturned on an appeal to the King and the judiciary. He was created Earl Howe and Baron Howe of Langar at the insistence of the King at the end of this term in 1788. During his period in office he faced a great deal of parliamentary and printed opposition for his attempted reforms, the reduction of personnel to a peace footing, and technical improvements. He was constantly in dispute with the Comptroller of the Navy, Sir Charles Middleton, whom he frequently overrided, whilst Pitt did little to support him and they disagreed over the prime minister’s ideas on economies planned for the navy. Howe was also castigated for his rigid refusal to grant personal favours, and although Pitt rarely asked for these, his friends bombarded Howe but he would do nothing for them, except on grounds of merit, claiming that for each posting there were twenty possible candidates. Consequently, Howe lost a great deal of popularity amongst his service contemporaries, particularly when he froze all promotions in 1787 until September, and it was with little regret on either side that on 16 July 1788 he resigned over the issue of the superannuating of admirals, and in particular Middleton’s unprecedented elevation to flag rank.

Howe might have left office but he continued to move in the highest circles, as evidenced in May 1789 when he dined Prince William Henry, Prime Minister William Pitt, and most of the cabinet at his residence in Bruton Street, London. He still continued to receive the odd sniping over his conduct in America, as illustrated when George Washington was installed as the president of the United States in 1789 and a comparison was made in the newspapers between the American’s plain brown suit and brown carriage and the ‘Heroes on this side of the water – Sir William Howe appears in the Order of the Bath and Lord Howe has an Earl’s Coronet on his carriage!’ On 1 July he attended the King and Queen during a walkabout in Weymouth, and he even ensured that a number of men fishing in the bay reeled in their catch for the appreciation of His Majesty to coincide with his return from a horse-ride. A sign of his wealth and standing as ‘the King’s Friend’ came when his daughter was ambushed when stepping into her coach at Covent Garden whilst attending the theatre with the royal family, and a spray of diamonds valued at three hundred guineas was snatched from her hair.

During the Spanish Armament in 1790 he was appointed the commander-in-chief in the Channel once more, although he formally assumed command after the fleet at Spithead on 4 July after it had been commissioned by his second-in-command, Admiral the Hon. Samuel Barrington. Additionally, he was granted the privilege of raising his flag as the temporary admiral of the fleet, a very high honour indeed. When he did join the fleet, it was aboard the Queen Charlotte 100, with Captain Sir Roger Curtis as his flag-captain, and Rear-Admiral Hon. John Leveson-Gower as his captain of the fleet, although by August Curtis had assumed the role of captain of the fleet with Captain Hugh Christian acting as the Queen Charlotte’s flag-captain. On 14 August Howe left Torbay with thirty-one sail of the line and cruised from Ushant to the Scilly Isles in readiness for any Spanish invasion before dropping anchor at Spithead on 14 September when it became clear that the Spanish had returned to Cadiz. In December he struck his flag.

He next hoisted it aboard the Queen Charlotte 100 in May 1793 when he took command of the Channel fleet upon the King s personal insistence at the start of the French Revolutionary War, having been asked to undertake this office on 1 February, and again being temporarily granted the flag of the admiral of the fleet. Although the better ships went to Vice-Admiral Lord Hood s Mediterranean fleet, Howe was able to secure his favourites Sir Roger Curtis, Hugh Christian, James Bowen, Robert Barlow and Edward Codrington as captain of the fleet, flag captain, master of the fleet, captain of his repeating frigate and signal lieutenant respectively. Howe was not a believer in the system of blockade and felt that frigates and detached squadrons should watch the Channel whilst he kept the fleet prepared for action at Torbay. Despite the fact that he was accused of skulking in the Devonshire anchorage he cruised in the Channel from July – August with seventeen sail of the line, falling in with French seventeen of the line on 31 July but being unable to bring about an action. He cruised again from October to December with twenty-two sail of the line but on 18 November was once more unable to bring a French squadron to action, much to the frustration of the newspapers at home.

In the following April, subsequent to a refit at Portsmouth, the fleet sailed from St Helens on 2 May with thirty-four sail-of-the-line in search of the French fleet of Villaret-Joyeuse and more importantly the American grain convoy. Two weeks later he learned that the French were at sea and by the end of May was able to bring them to battle. He gained his famous victory at the Battle of the Glorious First of June, where his fleet of twenty-five ships captured six, sunk one and dismasted ten of the French fleet of twenty-six ships under Rear-Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret-Joyeuse. The latter had left Brest in order to form an escort for the grain convoy which did enter port successfully, re-opening the debate on whether open blockade was the best policy.

The Battle of the Glorious First of June 1794

On 13 June Howe returned to Portsmouth with his prizes and two weeks later was visited by the King, the Queen and three princesses who presented him with a diamond-hilted sword. Some ill-feeling was generated when he was repeatedly requested by Lord Chatham, who was not a friend of his, to provide a list of those officers proving meritorious of honours. When he did present the list he specifically mentioned that it was incomplete, but nevertheless the government proceeded to issue gold medals to all those on the list, leaving an everlasting slur on those omitted. Howe himself was personally slighted by Prime Minister Pitt and his brother Chatham who indicated that the King s intention to make him a Knight of the Garter would not be in the public interest, and that he would be better to accept their offer of a marquisette, an offer he coolly refused. Fortunately the King was totally devoted to Howe and eventually awarded him the garter on 2 June 1797.

On 22 August he sailed from St Helens with thirty-seven sail-of-the-line, once more cruising in his favourite stretch of water from Ushant to the Scilly Isles, but by 21 September he was back at Torbay. A further sortie to sea from 9-29 November ended with the fleet returning to Spithead where it remained for the winter. By now Howe’s health was in decline, and whilst he wintered at Bath he remained in contact with the King who was anxious that his favourite admiral retain the overall command of the Channel Fleet, even if he were not fit to immediately take it to sea. A sortie by the Brest fleet at the turn of the year led to Howe resuming the command of the fleet at Spithead in January 1795, and after being detained by adverse winds he put to sea from Torbay on 14 February with forty-two sail of the line, including five Portuguese, in escort of the East and West India convoys. By then the French were back in port, and upon returning to Spithead after seeing them on their way Howe was granted leave once more at the end of February, whereupon he took to the waters of Bath to temper his gout. Admiral Lord Bridport now became temporary commander of the Channel fleet, a difficult position for both men which culminated in Howe claiming that his subordinate did not show him the proper deference, and stating to his flag-captain Curtis that if he ever did return to sea again he would refuse to serve with Bridport. The rift was not surprising as a degree of animosity had existed between the two officers ever since Howe’s spell at the Admiralty.

On the death of Admiral Hon. John Forbes on the 10 March 1796 Howe was created admiral of the fleet and general of marines, and in the following month he presided at the court-martial of Vice-Admiral Hon. William Cornwallis who had been accused of refusing to shift his flag into a frigate for passage out to the Leeward Islands. In 1797 he performed his last official service in bringing the mutinous seamen back to duty at Spithead following their insurrection on 16 April, for along with the King he was the only man the seamen trusted. Still suffering badly from gout he made his way down to Portsmouth from Bath where he was carried everywhere by his devoted men and rowed from ship to ship so that aboard each he could read out the King’s Pardon. Shortly afterwards he saw his flag come down for the last time, and noticeably he was not allowed to repeat his ship visits at the Nore Mutiny, which was perhaps an indication that the Admiralty did not approve of his conduct at Spithead. Certainly many officers, including Lord Bridport, thought that he was wrong to agree to the demands by many crews that their erstwhile officers not be allowed to return to their commands. Nevertheless, he was awarded the Order of the Garter on 2 June.

In retirement he remained clear in mind, if not body, and in December 1797 he and Admiral Duncan carried the colours up the aisle of St. Paul’s before the King in celebration of the British victories in the war.

Lord Howe died at his house in Grafton Street, Piccadilly, on 5 August 1799, after being advised to try electricity to drive the gout from his body – unfortunately it was driven straight to his head. He was buried in the family vault at Langar, Nottinghamshire and whilst his earldom became extinct his barony was acceded to by his eldest daughter.

He married Mary, the daughter of Colonel Chiverton Hartopp of Welby, Leicestershire on 10 March 1758 and had three daughters, one of whom, Sophia Charlotte married Penn Assheton Curzon, the heir to Viscount Curzon, in 1787, another, Mary, was at court, and the youngest married Lord Altamont. His wife died on 9 August 1800 at the age of sixty-eight.

He was the MP for Dartmouth from May 1757 until 1782, and although he was not affiliated to any political group he was an admirer of William Pitt the Elder, the 1st Earl of Chatham. Prior to his appointment to the chief command in America Howe declared that if able to chose he would not fight, but that if his duty demanded he would do so.

Due to his mother s royal connections Howe was able to move in the highest of social circles, and he was in effect a cousin of George III who considered him his favourite and called him Earl Richard . Howe in turn was a great advocate of the king, describing him upon any occasion a man very much above courting popularity, highly honourable and dependable.

Howe was tall and dark with heavy eyebrows, his features being strongly marked. His expression was harsh and foreboding, he was shy, awkward, difficult, taciturn, unfeeling, and ungracious in manner. Stern and severe, even Spartan, he was difficult to get to know and inarticulate, and he never smiled without good reason. The King opined that his reserve enveloped his meaning, and that it was difficult to ‘seize his mode of viewing things’. Horace Walpole who disliked him described him as being as unshakeable and as silent as a rock , and when he did speak in Parliament his ambiguous speeches were scarcely comprehensible, although he was heard with respect. Howe was nevertheless very deep, being intelligent and unable to fool, and he did not favour opinions unless they were firmly backed up with sound judgement. He openly admitted that he was a poor socialiser and host, unlike his brother, General Howe who gambled, drank, whored, and generally failed to take responsibility. However, although his shyness caused an unpopularity amongst many officers to such an extent that they did not drink to his health, his friends found him liberal, kind and gentle. He was a perfectionist who hated slackness although it was often said that his ships and fleets lacked discipline. Howe carried a signal book in action, when he lost his shyness and became more heated, even youthful at the thought of battle. His instructions were invariably long-winded and laborious but were understood by his officers.

Respected by most in the service for his attention to the practical aspects of the role, he was also very influential. Courageous, he was favourably viewed by both Jervis and Nelson, and was a friend of Lord Hood. ‘Lord Howe wore blue breeches, and I love to follow his example, even in my dress’ said the former. ‘The great immortal Lord Howe – first and greatest sea officer the world has ever produced.’ In turn he had a mutual disregard for Lord Sandwich although they did attempt to put aside their differences, whilst Howe disliked Lord Bridport and thought the future Admiral Lord Barham impossible.

A kind officer who put extreme trust in anyone, even a midshipman, whom he liked, Howe could be good humoured and was rarely jolted, although if his anger was aroused it could be violent. He considered himself unfortunate in not having a son, and he made up for this disappointment by patronising various younger officers such as Curtis, Christian and Codrington. He was adored by his men, not least for giving the sick and wounded rations from his own stocks. He also donated his not inconsiderable share of the Glorious First of June prize-money to the wounded, and he liked to use the word fellow .

A most thoughtful tactician, although Rodney had broken the line at the Battle of the Saintes it was Howe who perfected the ploy at the Battle of the Glorious First of June, using the incision to get to leeward of the French and hold them to battle. These were melee tactics that he had adopted from the lamented Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt. In the service he was known as Lord Torbay because of the loose blockade he operated over Brest. In 1776 Howe instituted a reformed signal book, far in advance of it s time.

Footnote – Some sources state that Howe was posted captain on 10 April 1747, whereupon he joined the Triton. This does seem feasible, and undoubtedly the use of the Julian calendar at that time is a cause of confusion. It is also possible that he was appointed to the Triton but did not immediately join her because of his head wound After much deliberation I believe that my version of events as above is the more likely, but if any reader is able to provide evidence to the contrary I’d certainly welcome it!