Mutiny on the Culloden – 4 December 1794

On 18 November, the Channel Fleet was at anchor off St. Helens when a gale swept in and drove the dilapidated Culloden 74, Captain Thomas Troubridge, onto the rocks, unshipping her rudder. Over the next four days the crew were ordered to jettison her water, her provisions, and even her shot in an attempt to lighten her, and when she did eventually re-float she had to be towed to Spithead by the frigate Fox 32, Captain Pulteney Malcolm.

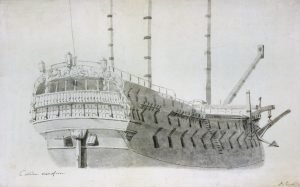

The Culloden was not a happy vessel. She had lost many men to sickness whilst employed under Captain Sir Thomas Rich in Rear-Admiral Alan Gardner’s disappointing Leeward Islands campaign during 1793, and after returning home to serve with the Channel Fleet she had played an inconspicuous part in the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794 under Captain Isaac Schomberg. She had then seen two further captains in the subsequent six months, these being Richard Rundle Burges, who had joined her in August, and Thomas Troubridge, who had taken command on 9 November, just nine days before her grounding.

Prior to his unfortunate and largely self-inflicted early death in 1807, the pugnacious uncompromising Troubridge would become a highly valued and sterling acolyte of both Admiral the Earl of St. Vincent and Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson; however, in November 1794 he was desperate to retrieve a reputation which had suffered from the capture of his frigate, the Castor 32, by a French squadron six months previously. A man of humble birth who had advanced through sheer force of personality and determination, Troubridge knew that he could be held accountable for the Culloden’s grounding, and that without ‘influence’ his career was on the line. He therefore resolved to play down the incident, and so whilst the Sampson 64, Captain Robert Montagu, was docked for repairs having suffered similar damage in the gale, Troubridge advised the Lords of the Admiralty that his own crew would repair the Culloden’s rudder at Spithead.

Their captain’s decision appalled the unhappy crew of the Culloden who already harboured concerns over the seaworthiness of their ship. Soon the officers began to pick up on their discontent, and over the subsequent fortnight matters escalated; there was a day when the men refused to bring their hammocks up from below, cries of ‘New Ship!’ were heard, and on the late evening of 4 December it became clear that something was about to go off when shot was rolled across the deck and cries of ‘Huzza’ rang out.

The first officer to go below and confront the men, the second lieutenant Anselm John Griffiths, was met with a volley of abuse and shot which forced him to scurry back on deck. The third lieutenant, Edward William Campbell Rich Owen then went down the fore-hatch with the ships’ corporal to be met by between forty and fifty men. Tall and imposing, yet humane, kindly, and cheerful, Owen was a man whom the Culloden’s knew well, as he had begun his career aboard the vessel in 1786, and having spent time on other ships had rejoined her six months earlier. The men laid out their grievance to varying degrees, the basic demand being that they follow the Sampson into dock, although more militant voices ignored the pleas of their calmer shipmates to call for the removal of the newly promoted first lieutenant, Tristram Whitter. The most strident among the throng proclaimed that if they were forced to go to sea they would hand the ship over to the French. Owen tried to reason with the men but now the blood was up, and he had to flee back on deck when objects were launched at him.

Now the mutiny began in earnest. Loyal men rushed up on deck to escape the insurrection, those who could not be trusted by the mutineers were harried aloft, and the ladders were hauled down to prevent any incursion by the marines, leaving some two hundred and fifty men, many of them Irish, below decks. Arms were handed out and two guns were pointed aft with lighted matches held at the ready. Some men turned to drink for Dutch courage, but most stayed sober as some sort of order was imposed, a watch system was set up, and an oath of loyalty was taken.

By now word of the mutiny had reached Troubridge who had apparently been dining ashore. On ship he attempted to talk to the men, but he was threatened by one of the die-hards who levelled a musket at him through the gratings. Nothing else occurred until 7 a.m. the following morning, when the petty officers held hostage since the outbreak of the disturbance were released. Meanwhile Admiral Lord Bridport, the Channel Fleet’s second-in-command who was standing in for the sickly Admiral Lord Howe after that officer had retired to Bath, had been informed by Troubridge of the disturbance and had dispatched one of his lieutenants, George Delance, to speak with the men. The mutineers accepted this emissary and politely but firmly repeated their demands that they either be moved to a new ship or have the Culloden docked, although again some voices insisted on the removal of the unpopular first lieutenant.

The affair was escalated to the commander-in-chief in Portsmouth, the venerable Admiral Sir Peter Parker, who in turn wrote to the Admiralty. On Saturday afternoon Bridport, together with Vice-Admiral Hon. William Cornwallis and Vice-Admiral John Colpoys, went aboard the Culloden in an attempt to reason with the men. It was to no avail. A letter was drafted by the mutineers in which they expressed their desire for an amicable resolution but also demanded to see any Admiralty correspondence, suggesting that they did not trust the local admirals. Conspicuously, as if emboldened by their success to date, the demand for Whitter to be expelled was included in the letter, and in taking a page out of the French Revolutionary manual it was signed by a ’delegate’. To preserve the anonymity of the ringleaders and create an impression of a collective will, the letter was handed up by unknown hands on a stick to an officer who passed it to Troubridge, who in turn took it to Bridport and opened it before the senior officer. Admiral Parker and the Admiralty were also appraised of the content.

Aboard the Culloden those more determined mutineers were growing frustrated, and when one man voiced threats about blowing up the ship word of this got back to the admirals via some loyal men trapped below. A popular and jovial Irishman officer, Captain Hon. Thomas Pakenham of the Invincible 74, was sent aboard, and although he managed to prove to the men that the Culloden was sea-worthy he was unable to prevail upon them to return to duty without an amnesty for the ringleaders. On Tuesday 9 December instructions were received from the Admiralty stating that ‘several captains were to go on-board and inform the crew, unless they immediately returned to their duty the Royal George, of 100 guns, and Queen, of 98 guns, would directly be laid alongside them’. In response to this directive Bridport advised that he could not comply, as the weather at Spithead was such that he could not communicate with any of his ships.

Eventually the Admiralty’s response to the mutineer’s letter was received – the local admirals were advised that they should accede to the demands by sending the Culloden into dock, but they were also instructed that the ringleaders should be held to account. Somewhat at a loss, Parker asked Pakenham to address the men again with Captain Lord Hugh Seymour of the Leviathan 74. There would subsequently be much conjecture over what was offered in this meeting, and Pakenham’s official report would later go missing, but it would seem that a deadline of thirty minutes was set, the delegates attempted to make terms that were unacceptable, and after twenty minutes they caved in and trooped up on deck where ten of the ringleaders were hauled out by Pakenham and Seymour and placed under arrest. Clapped in irons, these men were taken to the port-admiral’s ship from where they were removed to Rear-Admiral Hon. George Elphinstone’s flagship Barfleur 98.

On 15 December the first three men were tried for mutiny aboard the Caesar 80 at Spithead under the presidency of Cornwallis, and thereafter the trials continued until they were concluded on the 20th. Although two men were acquitted, eight others were found guilty, three of whom the court recommended for mercy. Attended by two catholic priests sent down from London, and having shown penitence and urged their shipmates to take heed of their fate and to not rebel in future, Francis Watts, James Johnson, Cornelius Sullivan, Jeremiah Collins and Joseph Curtain were brought to account at 11.45 on 13 January. Three of the men were hung from the starboard and two from the larboard fore-yardarm of the Culloden, with their bodies being cut down seventy-five minutes later. The other three men, having been pardoned by the King, were transferred to different vessels in the fleet.

The ill feeling caused amongst the crew of the Culloden by these executions was somewhat exacerbated as they felt that Captain Pakenham had given the mutineers some assurance of safety against prosecution. In the long term this grievance would be revisited, particularly in 1797 when the entire Channel fleet mutinied.

Members of Court Martial: Vice-Admiral Hon William Cornwallis (president), Rear-Admirals John Colpoys, Hon. George Keith Elphinstone: Captains Francis Parry. Lord Hugh Seymour, Charles Powell Hamilton, Hon. Thomas Pakenham, Sir John Orde, Christopher Parker, Erasmus Gower, Sir Andrew Snape Douglas, and Lord Charles Fitzgerald.