The Battle of Grenada – 6 July 1779

On 6 January 1779 Vice-Admiral Hon. John Byron’s battered fleet of ten sail of the line, a frigate, and a sloop, arrived in the Leeward Islands from North America in pursuit of the dozen ships of the Toulon fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral Charles Henri Jean-Baptiste, Comte d’Estaing. After joining Vice-Admiral Hon. Samuel Barrington at St. Lucia, Byron assumed the chief command of the station, and shortly afterwards, on 12 February, he was further reinforced with the arrival of Commodore Joshua Rowley and seven sail of the line in convoy. Concurrently a French reinforcement of some four or five sail of the line with attendant frigates and store-ships joined d Estaing at Martinique.

Over the next five months the two enemy fleets monitored each other over the thirty mile channel between St Lucia and Martinique. Occasionally d’Estaing put to sea to threaten a British convoy or squadron, but he always hastened back to port upon the appearance of Byron. The first of these occurrences came on 12 January when the French admiral contemplated a surprise attack on what he assumed to be the disabled British fleet at St. Lucia, but instead he found himself surprised and sent scurrying back to port when Byron s ships proved to be perfectly seaworthy. Another occurrence on 18 March saw a squadron under the command of Captain Walter Griffith of the Nonsuch 64 carried to the leeward of Martinique by the current, but when d Estaing put to sea in the hope of an easy capture Byron was able to slip his cable and rush out, whereupon the French turned tail. Clearly d Estaing s intention was only to attack commerce and the British islands, and he had no wish to become embroiled in a fleet action.

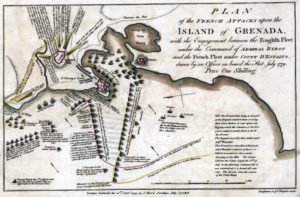

During the middle of June Byron was obliged to sail for St. Kitts in order to collect a huge homeward-bound trade convoy and escort it out into the Atlantic, but contrary winds and currents prevented him from weathering Martinique until the end of the month. His absence allowed d’Estaing a free hand, and he used it by easily capturing the island of St. Vincent on the 18th. The French commander-in-chief was then further reinforced on 27 June by the arrival of five sail of the line and three frigates from Brest under the command of Rear-Admiral Jean Toussaint Guillaume La Motte-Picquet de la Vinoy re, taking his strength to twenty-five sail of the line and twelve frigates. On 2 July he landed an expeditionary force of six thousand five hundred troops on the British held island of Grenada, overrunning it two days later, putting it to the sack, and capturing thirty merchantmen in the harbour.

Meanwhile Byron had finally returned to Gros Islet Bay on 1 July and received the intelligence that not only had St. Vincent been lost, but that an unknown fleet had been seen steering for Grenada. He immediately despatched a schooner under the command of his first lieutenant, John Thomas Duckworth, to reconnoitre d Estaing s anchorage at Fort Royal, Martinique, and this officer, who would subsequently enjoy a prominent but highly controversial career, returned with the false information that there were still thirteen sail of the line in the bay. Typically, Duckworth had failed to reconnoitre fully before being chased away, and he had failed to identify that the thirteen vessels were in fact transports and ships en-flute posing as d Estaing s fleet.

On 3 July Byron’s fleet consisting of twenty-one sail of the line and a small frigate in addition to twenty-eight other vessels, fourteen of which were transports carrying Major-General James Grant s troops, sailed from St. Lucia. Over the following days calm weather retarded the fleet s progress, and he received conflicting information as to the enemy s strength from the island of St. Vincent and then from two Grenadian schooners. When the fleet arrived off St. George s Bay on the south-west coast of Grenada at daybreak on the 6th to be greeted by warning flares from the outlying French frigates, Byron was still applying the greater credence to Duckworth s information, and he therefore expected to find an inferior enemy fleet at anchor.

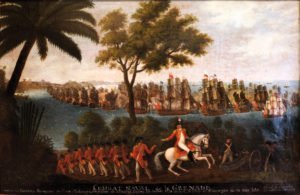

An image of the battle, kindly provided by Michel Bataillard, an author from Penmarc’h, France, who has been most helpful and inspirational in undertaking additional research for my work.

This remained his impression as in some confusion and in meagre winds the French ships slipped or weighed their cables and began coming out of St. George s at 4 a.m. Yes, there were a lot of ships, but only fourteen or fifteen appeared to be sail of the line. Having already signalled a general chase Byron now ordered Rear-Admiral Rowley, who had been detailed to superintend the troop landing, to quit the troop convoy which he had been escorting to windward of the fleet and to join the line of battle with his three sail of the line, the Suffolk 74, Vigilant 64 and Monmouth 64.

With the miserable wind at north-east by east, and the British approaching close inshore on the larboard tack in an inexcusably ragged order from the north, the French continued their unavoidably slow departure from their anchorage in a north north-westerly direction on the starboard tack. Byron noticed that a number of French ships were struggling to get out of the anchorage, and neglecting to form a strict line of battle he resolved to concentrate his attack at once on these vessels which would form the enemy rear.

In the British van, Rear-Admiral Barrington s flagship Prince of Wales 74 and her two consorts, the Sultan 74 and the Boyne 70, were enjoying a breeze that carried them well ahead of the remainder of the fleet, and they began receiving fire from the French at about 7 a.m., although initially they withheld their own fire. The same breeze now came to the assistance of the French who were finally able to get all their ships out of the harbour and form a line of battle to leeward on the starboard tack. It was only at this point that Byron realised he was facing twenty-five sail of the line and ten frigates, and that this was a force that was clearly more than a match for his own fleet. Nevertheless he retained the signal for a general chase and supplemented it with one for a close action.

The French were far from inclined to welcome an engagement however, and they bore up on the British approach whilst maintaining a fire which did great damage aloft to Byron s fleet. Being to windward and inshore of the French, Barrington was able to wear and engage the last three ships in the French line at about 8 a.m. although in so doing his ships came under fire from up to nine of the enemy before having the capacity to return fire. Barrington s action was perfectly in accordance with Byron’s signals, but it was to the commander-in-chief s misfortune that as these three ships came to action the remainder of his fleet fell becalmed in the lee of the island. Eventually the Grafton, Cornwall and Lion, which were inexcusably well offshore from the rest of the British line, were able to catch the light airs, but this left them in close contact with the French on opposite tacks and they were engaged and virtually disabled by almost the whole of d Estaing s fleet as it passed them.

Eventually coming around on the same tack as the French, Byron decided to change his tactics and to force a close action with their van and centre. Barrington’s ships were now forced to crowd on sail in order to reach up on the enemy’s van, and they engaged any of the French line which allowed them to do so on the way. The action was nevertheless a hot one, with the wounded Captain Sawyer of the Boyne directing affairs from a chair on his quarterdeck, and Vice-Admiral Barrington receiving a ball in the arm. Having as yet been unable to join the rear of the British line, Rowley with the Monmouth, Suffolk and Vigilant bore down upon the head of the French line to support the beleaguered Barrington, engaging the enemy van from to windward whilst the vice-admiral and his consorts fought their way up the leeward side. So conspicuously did the Monmouth engage the French that her opponents would later raise their glasses to the little black ship .

By noon a partial action was taking place, and having been engaged with thirteen of the enemy in a crescent around them for three and a half hours the active British ships, in particular the excellently handled Prince of Wales and Monmouth, suffered badly. Conversely at the rear of Byron s line Rear-Admiral Hyde Parker s squadron remained largely unengaged. For an hour and a half the firing raged, and Byron, who was concerned that the roving French frigates might attack his convoy, retained his signal for close action, although that for a general chase was withdrawn. But then the British lost the wind once more, and the commander-in-chief watched in despair as his plans to bring on a general action were thwarted by the calms. For someone who had been so consistently betrayed by stormy weather as to earn the nickname Foul Weather Jack the irony was unbearable.

Despite their numerical superiority the French clearly preferred the protection of their new conquest to the prolonging the engagement, and by three o’clock d’Estaing had manoeuvred out of range and was wearing his fleet to return to Grenada. Realising that this move jeopardized the safety of the badly mauled Lion, Cornwall, Grafton and Fame which were well astern and between the two fleets, Byron also tacked, but apart from a few ragged broadsides the French amazingly made no effort to finish off these crippled vessels and the action came to an end. On the French side Captain Pierre Andr de Suffren, whose Fantasque had lost twenty-two men killed and forty-three wounded, could hardly credit the fact that d Estaing was ignoring the opportunity to easily capture these vulnerable ships.

The Lion having suffered fifty-one casualties eventually made the best of her way before the wind to Jamaica, carrying what sail she could on her foremast and the stumps of her main and mizzen masts and eventually arriving on 20 July. The Monmouth, which had been unable to tack with the rest of the fleet when Byron replicated the French manoeuvre, parted company for Antigua.

It having been agreed that any attempt to recapture Grenada was out of the question due to the superiority of the French defences, Byron ordered the troop transports to return to the Basseterre Roads, St Kitts that evening. When the morning came d Estaing was nowhere in sight, so presuming that he had retired to Grenada Byron also set sail for St. Kitts. Arriving at the island on 15 July he attempted a refit with the paltry stores available whilst Captain Sawyer of the Boyne and the wounded Admiral Barrington made their way home with his despatches, arriving in London on the evening of 9 September. Although d’Estaing felt confident enough to parade his fleet of twenty-eight ships off St Kitts at the end of the month he showed no inclination to force another battle and eventually he returned to San Domingo.

The casualties in the battle amounted to 183 dead and 346 wounded on the British side, and 190 killed and 759 wounded on the French. However, with seven ships disabled, and having also failed to retake Grenada, the British had clearly suffered the worst from the engagement. A month later Byron, worn out by his command, returned to England, and although he enjoyed a pleasant enough reception from the King and from the Admiralty it was certainly not one that would have been bestowed upon the hero of the hour. The general consensus was that although he had fought bravely the advantage of the wind and the French requirement to maintain contact with Grenada had been thrown away by an instant attack in an ill-formed line. It could have been far worse however, for had d Estaing shown more tenacity in attacking any of the Lion, Cornwall, Grafton, Fame or Monmouth, then the French could have claimed a clear victory.

With Byron and Barrington having returned home the command of the Leeward Islands station devolved upon Rear-Admiral Hyde Parker who retained it until the arrival of Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney in the following March. Meanwhile on 9 October d Estaing was wounded leading an assault on the recent British capture, Savannah, and shortly afterwards he capitulated to the will of his captains, who with their fever-ridden ships in a poor state of repair feared the approaching hurricane season, and his fleet returned to France.

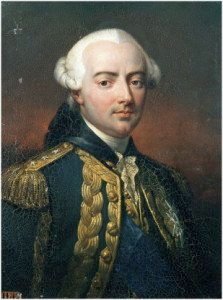

Sadly d Estaing was to lose his life to the Republican guillotine in 1794 after being found guilty of testifying on behalf of Queen Marie-Antoinette during her trial.

Ships participating and casualties:

French Fleet:

2 x 80 guns: Tonnant; Languedoc;

11 x 74 guns; Hector; Fendant; Magnifique; Annibal; Marseilles; C sar; Robuste; Diad me; Guerrier;

Protecteur; Z l :

1 x 70 guns: Dauphin Royal;

7 x 64 guns: Fantasque; Provence; Vaillant; Vengeur; R fl chi; Art sien; Sphinx;

1 x 54 guns: Sagittaire;

3 x 50 guns: Amphion; Fier- Rodrigue; Fier;

Frigates: Diligente 28; Fortun e 32; Blanche 32; Alcm ne 28; Amazone 32; Boudeuse 32;

Chim re 28; Iphig nie 32;