The Sinking of the Royal George – 29 August 1782

On 17 March 1782 the Royal George 100, flagship of Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, joined the Channel Fleet at Portsmouth following a comprehensive refit at Plymouth. A few weeks later she inherited a new captain, Martin Waghorn, who had made a rapid ascent to his lofty position from that of eighth lieutenant aboard the Victory just two years previously, and during the summer the Royal George played a full part in the Channel Fleet’s onerous campaign. Having returned to anchor at Spithead she was, by the evening of 28 August, almost ready to sail with the rest of the fleet to attempt the relief of Gibraltar.

The Royal George was twenty-six years old, two hundred and ten feet long, weighed over two thousand tons, and carried a nominal crew of eight hundred and fifty men. She had seen constant service in the previous war, having been employed as Admiral Sir Edward Hawke’s flagship at the Battle of Quiberon Bay and flown at differing times the flags of Admirals Rt. Hon. Edward Boscawen and Lord George Anson. She had been laid up at Plymouth from 1763 until 1778, although in 1768 she had undergone a major overhaul. Having been re-commissioned in July 1778 she had served as the flagship to Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Harland, Vice-Admiral George Darby, and Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart-Ross, had participated in Admiral Sir Charles Hardy’s retreat up the Channel, and been present at Admiral Sir George Rodney’s Moonlight Battle off Cape St Vincent and his subsequent relief of Gibraltar.

On the evening of 28 August Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt made a private visit ashore to an old friend and ex-shipmate, William Nichelson, the master attendant of the Portsmouth Dockyard, and at the same time hundreds of wives, children, girlfriends, and prostitutes gathered aboard the Royal George to spend a last night with the men. Come the next morning there were eight hundred and twenty-odd men and over three hundred and fifty women and children aboard, but missing ashore, despite the instructions given by the admiral to the contrary, were three important warrant officers, these being the sailing master, the gunner and the boatswain.

At 7 a.m., whilst the remaining lighters were lining up alongside the great ship to deliver their loads, Thomas Williams, the Royal George’s carpenter, requested that the ship be heeled over so that a faulty cistern pipe about three feet below the waterline could be replaced. By 7.45 a.m. all the lower and upper deck larboard guns had been run out to their fullest extent, and the starboard guns had been drawn in mid-ships, but as this arrangement proved insufficient to induce the eight per cent heel that was required to attempt the repairs more guns on the middle deck and a large quantity of shot were hauled across from the starboard to the larboard side of the deck.

At the time the ship was anchored with her head pointing towards Cowes on the Isle of Wight, and with the tide on the flood. The sea was calm and there was little concern as to the effect the heel would have on the lower larboard gunports. The officer of the watch changed, the men went to breakfast, as did Captain Waghorn with Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt, and at 8.45 the 50-ton lighter Lark came alongside to begin unloading casks of rum through the open gunports.

As the flood tide neared its height it began to induce a choppier sea which brought about an order from the first lieutenant, George Saunders, to secure two of the gun-ports to prevent spray from coming aboard. Fatefully however the ports were merely lowered, not secured, yet as the rum began to come aboard there remained little cause for concern below decks; indeed, some of the men were taking the opportunity to chase the mice which had rushed up from the depths of the ship and were thrashing about in the puddles caused by the spray.

Shortly after 9.00 a.m. the carpenter appeared on deck to request that the officer of the watch order the larboard guns to be hauled in so that the heel could be reduced. In a state of confusion he attended the wrong lieutenant, later reported to be Monins Hollingbury although this may not have been the case. In any event the officer, being aware that the artificers replacing the cistern pipe were still calling for more heel to the ship, and suspecting that Williams was exhibiting his usual attitude to petty difficulties, told the carpenter to go about his business. Nearby, and having left Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt writing at his desk, Captain Waghorn was walking the deck with the actual officer of the watch, Acting-Lieutenant Philip Durham, in total ignorance of the troubles that were unfolding down in the hold.

The officer’s rebuttal of the carpenter arguably consigned the Royal George to its fate, for below the heavy rum casks had carelessly been stacked too near to the gunports, and the sills were gradually slipping below the level of the water as the tide reached its height. Imperceptibly, then more identifiably, the sea began to pour in. Alone amongst all the officers only Mr Williams seemed to recognise the jeopardy that the arranged heel had placed the ship in, and in no time he was back on the quarterdeck crying out that the ship was unable to take the strain. Again, the officer dismissed his entreaties, telling the carpenter that if he knew how best to manage the ship then he should take command. But by now others were becoming aware that something was amiss, not least the seaman on the gangways and in the waist who were party to the exchange between Williams and the officer, and who bristled at the lieutenant’s intransigence.

Confirmation came almost immediately from the artificers working on the cistern pipe who suddenly cried out ‘avast, avast heeling, she is quite high enough! The ship is out of the water!’ The carpenter and the first lieutenant hurried off the deck at the same time as the sailing master, Richard Searle, clambered aboard and rushed up to Captain Waghorn, shouting out that the ship was taking in copious amounts of water. Acting-Lieutenant Durham called for the drummer to beat to quarters so that the men could be summoned to run out the starboard guns and run the larboard lower decks guns in. Whether the boy ever reached his drum is doubtful, but the men who had already been party to the carpenter’s outburst fully understood the perilous situation of the ship, and they were already rushing through the hatches to try and move the guns.

But it was already too late. The water was pouring into all the exposed gunports, and objects on the higher side of the deck were toppling towards the lower side. When the men reached the guns they found that the increasing heel of the ship prevented any from being moved. Suddenly the whole ship shuddered and the masts began to tilt sideways towards the sea. Captain Waghorn desperately tried to get into the admiral’s cabin, but the doors were jammed by the extent of the heel.

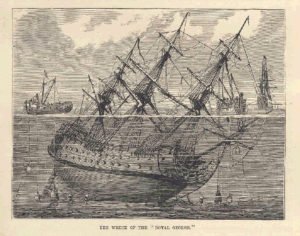

The Royal George began to topple over further and further, crushing the rum-lighter alongside which only momentarily held the great ship at bay, and falling onto her larboard beam with her masts lying flat across the water. She remained in this position for some minutes, enabling hundreds of people to scramble up on to the starboard hull which still remained above the water. But then with a resounding and deathly explosion of air which was thrust out by the water that was swamping her she sunk below the surface, rebounded off the seabed, and settled almost upright with her fore, main and mizzen topmasts pointing skywards, and the tips of her bowsprit and stern flagstaff also visible.

Spithead resounded to the ships of the fleet firing signal guns, and boats rushed to the scene, being aided by the incoming tide and the north-westerly breeze. At first the swirling maelstrom of turbulent water thrown up by the massive ship’s sinking prevented them from getting close enough to begin any rescue, but as the sea settled they began picking up the people in the water whilst for the moment leaving those who had climbed the rigging and were regarded as safe.

As soon as he had realised that the ship was going down, Captain Waghorn had seized a young lad named Pierce and thrown him over the rail into the sea where a seaman kept him afloat until they were able to swim back to the settled ship and perch on the maintop. Waghorn himself could not swim, yet he was saved by one of his own men who helped him cling on to the mizzen top-sail yardarm until rescued. Lieutenant Durham managed to grab hold of a hammock in the water, but he then had to fight off a marine who was dragging him under before managing to float on a spar to the signal halliards. Here a seaman helped him up to the masthead where he sat for an hour until he was picked up with the carpenter and put to bed aboard the Victory. Sadly, one-hour later, and despite the efforts of two women to revive him beside the galley fire, Williams died. Acting-Lieutenant William Richardson launched himself into the water from the poop, but not before he had removed his precious lieutenant’s coat and bundled it under his arm. A tiny midshipman called John Crispo jumped off the quarterdeck and managed to swim to a nearby vessel, whilst another youth was propelled up through a hatchway by the force of the water, and although struck by a falling cannon that broke three of his fingers he survived to be picked up by a boat. A child who knew his name only as Jack lost both his parents but survived by clinging on to a sheep that had somehow come to the surface. The boy would later be adopted by the owner of a wherry who pulled him out of the water, and he would be suitably christened John Lamb .

Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt’s body was never recovered, but that of the first lieutenant, George Saunders was found a few days later under the stern of an East Indiaman, the Montague. For days afterwards bodies rose to the surface and were towed ashore by the watermen. In all only two hundred and fifty-five people survived the sinking, of whom just eleven were women and one a child. Estimates as to the number of dead ranged from nine hundred to perhaps as many as twelve hundred, including Captain Waghorn’s son William, a midshipman, and one of his messmates who had set off for the shore in a boat shortly before the disaster but had then come back aboard the Royal George to collect his dirk. Fortunately, the boat and its occupants survived.

The court martial into the loss of the ship opened aboard the Warspite in Portsmouth Harbour on 9 September. It was presided over by Vice-Admiral Hon Samuel Barrington, who was joined by Rear-Admirals John Evans, Mark Milbanke, Alexander Hood, Sir Richard Hughes, Commodores William Hotham and John Leveson-Gower, and Captains John Allen, John Moutray, John Dalrymple, Jonathan Faulknor, Sir John Jervis and Adam Duncan. The verdict, which cleared the officers of the Royal George of any blame for her loss, was unpalatable to some, and there was a hint of political expediency in order to avoid any imputation of blame on the Navy Board and the Admiralty. Rather than condemn the failure to correct the heel in line with the carpenter’s urgent requests, the tragedy was attributed to the breaking away of a large section of the ship’s frame which was caused by decaying timbers that had been unable to withstand the heeling of the ship.

Various artefacts were salvaged from the wreck of the Royal George, but despite the plans of officers such as Captain Sir Hyde Parker, and a lacklustre attempt to raise her using the Royal William and Diligente, it appears that in ignoring her threat to the busy lanes of shipping the Navy Board preferred her to remain where she was. Her masts remained visible for many more years at low tide and the last of them was only destroyed in 1794 when a frigate ran it over in the dead of night. She was eventually broken up under water and cleared away in a major diving operation during the 1840’s.

The sinking of the Royal George and the loss of so many lives including the highly-valued Kempenfelt had a huge impact on the country, not only at the time but for many decades afterwards, and the public interest was not unlike that which resulted from the loss of the Titanic more than a century later. A poem by William Cowper commemorated the sinking, and in particular it celebrated the lost rear-admiral whose stock at the time was so high that come the naval mutinies of 1797 the spirit of Kempenfelt was invoked to inspire dialogue between the disaffected seamen and the naval establishment.