Action of Monte Cristi – 20-22 March 1780

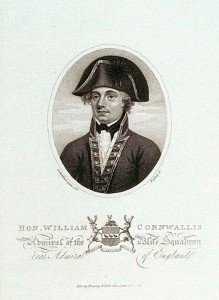

Operating out of the Jamaican station where his badly damaged ship had fled following the Battle of Grenada the previous July, Captain Hon. William Cornwallis of the Lion 64 was cruising in the Windward Passage to the north of Monte Cristi, Haiti, in company with the Bristol 50, Acting-Captain Hon. Thomas Pakenham for the sickly Captain Toby Caulfield, and Janus 44, Captain Bonovier Glover, when on the morning of 20 March his ships fell in with a superior French squadron. This force, consisting of the Annibal 74, Diad me74, Refl chi 64, Amphion 50, and Amphitrite 32, was under the flag of Rear-Admiral Jean Toussaint Guillaume La Motte-Picquet, and was escorting a convoy from Martinique to Cap Fran ois. Prudently despatching his charges to safety, the much-respected French admiral soon piled on sail to the north-west in pursuit of Cornwallis.

In order to meet the enemy threat Cornwallis formed his three ships in line ahead, but he was soon overreached by the French flagship Annibal 74 when she came in range at about 5 p.m. A general action did not ensue however, for despite his superiority La Motte-Picquet showed no further inclination to close with the British that evening. Instead a long-range cannonade continued through to the early hours of the following morning.

Come daylight a calming wind had drawn the Janus well away away from her consorts to leeward, so that that she became engaged with La Motte-Picquet s flagship, losing both her mizzen-top and fore-topgallant masts, but in turn inflicting more than superficial damage to the Annibal by using her manoeuvrability to hang off the Frenchman s quarter and stern. At some time in the morning Captain Glover, whose recent career had been plagued by a court martial called upon him by his officers, and who carried the stigma of not having exerted himself so well as was expected , died in his cot below of natural causes. The command devolved upon his first lieutenant, George Hopewell Stephens, an event which at the time was unknown to Cornwallis.

Wishing to support the Janus, whose situation was becoming precarious with the approach of two of the Annibal s consorts, the boats of the Lion and Bristol were hove overboard and employed in towing the two heavier ships to the support of the frigate. After a three hour long-range engagement, one in which the Lion had to replenish the Bristol s stock of powder, the French hauled off to make good on their repairs, showing no interest in putting any of their ships at risk, but rather looking to the protection of their damaged flagship.

Having effected repairs to his own squadron and somewhat unfairly castigated Lieutenant Stephens for not allowing Captain Glover the opportunity to restore his reputation by dying on deck, Cornwallis was rewarded for his obstinacy at dawn the next morning when the Ruby 64, Captain John Cowling, and two frigates, the Pomona 28, Captain Edmund Nugent, and Niger 32, Captain John Brown, came in sight. Their appearance was a hammer blow to La Motte-Picquet, who with a fresh breeze coming on from the east north-east had envisaged resuming the engagement with the inferior British squadron within the hour. At 6.30 a.m. the French admiral decided to abide by standing instructions to keep his ships in being, and he retreated before what he now considered might be a superior force. Signalling his squadron to make for Cap Fran ois and rejoin the convoy, La Motte-Picquet crowded on sail, and after a five hour chase Cornwallis threw over the pursuit, his squadron having sustained just twelve casualties in the three-day action.

The disabled Janus returned to Jamaica on 25 March and apprised the commander-in-chief, Vice-Admiral Sir Peter Parker of the events. Captain Horatio Nelson of the Hinchingbroke 28 was appointed to replace the late Captain Glover in command of the Janus, being recalled from the naval command of an expedition that had been sent to capture the Spanish forts guarding the River San Juan s approach to Lake Nicaragua. This recall could not have been more opportune, for of the eighteen hundred men who were sent on this task only four hundred survived a fever, including just ten of the Hinchingbroke s two hundred-strong crew. After a brief service on the Janus it was plain that the fever-ridden Nelson was also too ill to continue in command, and he was invalided back to England aboard the Lion under the care of his friend, Cornwallis.

As for Lieutenant Stephens, who was considered to be a decent and worthy officer, Cornwallis would never forgive him for what he considered to be his dereliction of care towards the honour of his good friend Captain Glover. Over twenty years later, as Admiral Hon. William Cornwallis, commander-in-chief of the Channel Fleet, it took him less than two hours to again unfairly castigate the promoted Captain Stephens when that officer joined his fleet in command of the Brunswick 74.