Admiral Richery attacks Newfoundland and Labrador – August / September 1796

With a Spanish alliance nearing agreement, the French Republic was keen to invoke their southern neighbour’s assistance in springing a squadron of seven sail of the line under the command of Rear-Admiral Joseph de Richery, which for some months had been blockaded in Cadiz by a British squadron of seven sail of the line commanded by the sickly Rear-Admiral Robert Man.

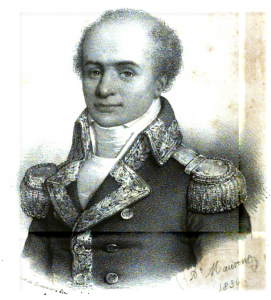

Approaching his thirty-ninth birthday and having been born to a modest noble family, Richery had seen service in the American Revolutionary War, including in the East Indies under the command of the esteemed Rear-Admiral Pierre Andre de Suffren, and he had commanded a ship in the Far East and off Australia for a great deal of the ensuing peace. Returning to France, he had been promoted captain of the Bretagne 100 on the resumption of hostilities with Britain in 1793, and although briefly sidelined from the Navy following the mutinies at Brest in 1794, he had soon been re-instated and promoted to flag rank. Commanding a division of six sail of the line and three frigates operating out of Toulon, he had intercepted the Levantine convoy in October 1795, capturing thirty vessels along with an escort ship, the British prize Censeur 74, and he had carried these into Cadiz where he had since been blockaded by Rear-Admiral Man.

The British Admiralty was aware that in addition to Richery’s squadron, there were twenty Spanish sail of the line at Cadiz, and accordingly they had warned Man not to risk attacking the French if, as seemed increasingly likely, they put out to sea with the Spanish fleet. On 13 July orders were given to Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, bound for Gibraltar from Spithead with a huge convoy destined for all parts of the globe, that he should supersede Man off Cadiz once he joined company. Secret orders issued to Parker two days later, but not to be opened until he was off Cape Finisterre, further instructed him that in the event of Richery having already sailed with a Spanish fleet, he should consider whether their destination was the West Indies, and by his own judgement make for Barbados with Man’s squadron to monitor the enemy’s activities.

On 26 July, with the departure of Richery and the Spanish fleet apparently imminent, Man sailed away from the blockade of Cadiz to reinforce the bulk of the Mediterranean Fleet off Corsica on the orders of his commander-in-chief, Admiral Sir John Jervis. His departure allowed Richery’s squadron of seven sail of the line, which now included the recaptured Censeur, and three frigates to leave port on 4 August with the Spanish fleet commanded by Admiral Don Juan de Langara, a division of which parted company two days later off Cape St. Vincent and returned to port, leaving ten sail of the line under Rear-Admiral Jose de Solano y Bote to escort the French three hundred miles out into the Atlantic.

On 11 August, with news yet to be received of Richery departure from Cadiz, Vice-Admiral Parker with his flag aboard the Queen 98, Captain Man Dobson, departed St. Helens with his convoy of one hundred and seventy sail escorted by four sail of the line, four frigates, a sloop and two smaller vessels. Eight days later he reached Cape Finisterre where he opened his orders, and where the convoy split into its various destinations under the escort of the individual men of war. On the 23rd he at last received intelligence of the Franco/Spanish departure from Cadiz, and sending orders for Man, who he believed was at Gibraltar, to return to England with two sail of the line and despatch the remaining five to Barbados, he sailed for the latter island. In the event his dispositions would be to no avail – Richery had gone elsewhere.

The first news to reach England of Richery’s foray from Cadiz came via the Paris newspapers, which had reported his departure on 20 August. As his destination was unknown in London, there was much speculation that the Spanish might simply be escorting him to Toulon, or to a French Atlantic port. Rumours that an engagement had taken place between Richery and Mann were soon discounted with the knowledge that the latter had left the station before the allied armada’s departure, and then the frigate Stag 32, Captain Joseph Sydney Yorke, returned to Portsmouth from Parker’s convoy to report that the French had almost certainly sailed for Saint-Domingue. Speculation also mounted over the destination of Solano’s ten sail of the line, with reports that it could be America or Santo Domingo.

Meanwhile, in adhering to previous orders to destroy the British settlements in Newfoundland, which he had been forced to defer after capturing the Levantine convoy and taking it into Cadiz, Richery had continued his passage across the North Atlantic. On 28 August he arrived off Newfoundland, where all bar one of the Vice-Admiral Sir James Wallace’s meagre force consisting of the Romney 50 and four frigates were on detached duties protecting the North American waters against French privateers. The single exception, the frigate Venus 32, Captain Thomas Graves, was at the capital St. Johns, and when news was received of the French appearance off the island, her men were quickly sent ashore to man the batteries and she was placed across the entrance to the harbour as a block ship. Upon approaching St. Johns in rough weather on 2 September, Richery decided not to attempt an attack on the defences under the prevailing conditions, but instead he headed south towards Petty Harbour, which was destroyed, and then on to Bay Bulls, where a far easier target presented itself.

There followed over the next few weeks a destructive orgy that decimated the British fishing installations and fleet. At Bay Bulls, the battery protecting the settlement was dismantled, the cannons spiked, and the buildings razed to the ground. On 5 September, the able Commodore Zacharie Jacques Théodore Allemand was detached with the Duquesne 74, Censeur 74, and frigate Friponne 32, to attack Labrador, whilst bad weather kept Richery at Bay Bulls until the 8th. Sailing out of the bay under the watchful eye of a naval lieutenant on a nearby hill, he decided that the storm damage to his ships meant that he would have to abort plans to attack the settlement at Placentia, as per his previous instructions, so instead he bent a course for the former French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off Newfoundland’s southern coast. Here he was able to land without opposition and destroy all the buildings, fishing installations, boats, and community buildings.

In the meantime, Commodore Allemand had been delayed by the murky weather that was typical of the region, and it was not until 22 September that he arrived off the settlement of Chateau on the Labrador coast at the entrance to the strait of Belle Isle, by which time many of the fishing vessels had already departed for Europe. Here the fort responded to his summons with a strong cannonade, and when the French did land on the next day, the inhabitants burnt their own settlement. Allemand then made for the rendezvous with Richery near Belle Isle, where he remained until 7 October before setting off for home with his three ships.

Back in Britian, it was not until the latter part of September that Richery’s appearance off Newfoundland was confirmed with the arrival from those waters of the frigate Andromeda 32, Captain William Taylor. Over the next few weeks reports of Richery’s depredations proliferated, many of them false, including an account which was widely believed in France that St. Johns had been captured and a thousand prisoners had been transported to Saint-Domingue. Only when reinforcements from Bermuda under the commander-in-chief of the North American station, Vice-Admiral Hon. George Murray, reached Newfoundland on 27 September were accurate reports of Richery’s raid sent back to England, and these confirmed that whilst many prisoners had been dispatched on a cartel to Halifax, Nova Scotia, some three hundred had been taken back to France, and that up to a hundred fishing boats had been destroyed.

In the hope of intercepting Richery on his voyage home, a division of the Channel Fleet under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Roger Curtis was dispatched to the Bay of Biscay. For a short while he paraded off Rochefort, but having sailed for England on 3 November, he missed Richery’s arrival at that port two day later after the French admiral had previously been chased away from Lorient by a division of the Channel Fleet. Ten days later, on 15 November, Allemand safely entered Lorient with the three ships under his command.

Vice-Admiral Parker’s escort:

| Queen 98 | Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker |

| Captain Man Dobson | |

| Brunswick 74 | Rear-Admiral Richard Rodney Bligh |

| Captain Herbert Browell | |

| Valiant 74 | Captain Eliab Harvey |

| Polyphemus 64 | Captain George Lumsdaine |

| Oiseau 36 | Captain George Stephens |

| Caroline 36 | Captain William Luke |

| Druid 32 | Captain Edward Codrington |

| Stag 32 | Captain Joseph Yorke |

| Raven 18 | Commander John Giffard |

Rear-Admiral de Richery’s Squadron:

1 x 80 guns: Victoire:

6 x 74 guns: Barras, Berwick, Censeur, Duquesne, Jupiter, Révolution;

3 x frigates: Embuscade 36, Félicité 36, Friponne 32;