Sir Roger Curtis

1746-1816. He was born on 4 June 1746 at Downton, Wiltshire, the only son of a wealthy tradesman and farmer, Roger Curtis, and of his wife Christabella Blachford.

In 1762 Curtis entered the Navy upon the Royal Sovereign 100, Captain Robert Hathorn, the flagship of Vice-Admiral Francis Holburne, and following the end of the Seven Years War he found a berth aboard the Assistance 50, Captain James Smith, sailing for the coast of West Africa. He then moved to the Medway guard-ship Augusta 64, Captain Matthew Whitwell, and thereafter spent three years aboard the frigate Gibraltar 20, Captains Richard Braithwaite, Lucius O’Brien and William Long, serving off Newfoundland and later in home waters. During 1769 he moved into the Venus 36, Captain Hon. Samuel Barrington, and transferred with that officer a year later to the home-based guardship Albion 74.

On 19 January 1771 Curtis was commissioned lieutenant and he returned to Newfoundland aboard the sloop Otter 14, Captain John Morris. Here, as well as gaining a thorough understanding of the Labrador coastline, its fisheries and the local inhabitants, he had the good fortune to become a favourite of the commander-in-chief, Commodore Molyneux Shuldham. This relationship bore fruit when the promoted Rear-Admiral Shuldham was appointed the commander-in-chief of the North American station in 1775, and Curtis joined the flagship Chatham 50, Captain John Raynor, when she began fitting out at Portsmouth at the end of July prior to sailing across the Atlantic in December.

Sir Roger Curtis

On 30 April 1776 Curtis became the acting-commander of the sloop Senegal 14, and he was commended by the new commander-in-chief, Vice-Admiral Lord Howe, for taking charge of a number of army transports, including that of General Sir William Howe, and attending to their safe conveyance to New York in spite of having previously been issued with orders to seek out and destroy a number of enemy privateers. Awarded a commander’s commission with seniority from 11 July, he assisted in the superintendence of the boats landing the army on Staten Island during the New York campaign of July – October.

On 30 April 1777 Curtis was posted captain of Lord Howe’s flagship, the Eagle 64, serving in the Philadelphia Campaign from August to November, the defence of New York in July 1778 and operations off Rhode Island in August. He returned to England with Howe on 25 October and left the Eagle shortly afterwards. During 1779 he held the brief command of the Terrible 74, deputising for Captain Richard Bickerton in the Channel, but having refused an East Indian posting with the Eagle he was otherwise beached.

In the autumn of 1780 he joined the frigate Brilliant 28 and sailed from Portsmouth for Gibraltar at the beginning of November. Upon reaching the Mediterranean his command was chased into Minorca by two Spanish frigates and a xebec, and here Curtis allowed the Brilliant, Porcupine 24, Captain Sir Charles Knowles, and the Minorca 18, Captain Hugh Lawson, to be blockaded by three French frigates for some five weeks. He was later charged by his first lieutenant, Colin Campbell, with failing to attack the enemy, which that officer claimed had a combined firepower less than that available to Curtis. The charge was almost certainly brought about by a personal enmity, even though subsequent investigations suggested that that the French were indeed inferior in firepower.

By April 1781 Curtis had assembled a convoy of store ships larger than that which Admiral Sir George Rodney had delivered to Gibraltar the year before, and once he had slipped it into the Rock on the 27th he remained in command of the naval forces to lead its glorious defence against the Spanish siege. On 7 August he personally commanded two gun boats and the boats of the squadron which put out to cover the arrival into the Rock of the sloop Helena 14, Captain Francis Roberts, fighting off fourteen Spanish gunboats from Algeciras to do so, and on 27 November he served as a volunteer in a successful assault by the troops and two brigades of seamen on the Spanish advanced works.

Allied forces lay siege to Gibraltar 1782

Curtis earned great praise for his command of the gunboats in action with the enemy’s battering ships during the Grand Assault on 13 September 1782, and in particular for his humanity in rescuing four hundred Spaniards from their blazing hulks, during which operation his pinnace was caught in an explosion and his coxswain killed. In September he commissioned the captured Spanish San Miguel 74, and on 18 October Admiral Lord Howe arrived to relieve Gibraltar. After going aboard the Victory 100 to greet his old commander, Curtis was unable to get back ashore and was obliged to return with the fleet to England, accepting the appointment of captain of the Victory on 6 December in place of Captain Henry Duncan who had returned home with despatches.

Upon reaching London Curtis was knighted for his defence of Gibraltar, and as well as having his memoirs published he was feted by society for his gallantry and humanity, awarded the thanks of Parliament, given a 500-guinea pension, and honoured with the role of ambassador to Morocco and the Barbary States. At the request of the beleaguered governor he was then sent straight back to Gibraltar, sailing in January with the rank of commodore aboard the Thetis 38, Captain John Blankett, and arriving at the Rock on 10 March. In April he visited Tangiers aboard the Brilliant to deliver gifts to the Court of Morocco, by July he was at Leghorn, and with the war having ended he arrived back at Portsmouth in December.

During the peace Curtis commanded the guard-ship Ganges 74 at Portsmouth from May 1784 until paid off December 1787, being attached to Commodore Hon. John Leveson-Gower’s squadron of Observation in the summer of the latter year, although in the event this force did not put to sea. At some point in 1787 he was also sent on a secret mission to Sweden where he discussed their superior gunboat designs with a view to constructing improved vessels for the defence of Gibraltar in any coming war. In October 1788 he and Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian tested a prototype gun-boat at Portsmouth of the type used by the Spanish in the Siege of Gibraltar, and he then undertook a two-month mission to Stockholm in the early summer of 1789 to ensure the constancy of supplies in the event of war, returning to London from Holland on 10 June.

In May 1790 Curtis was presented to the King by Admiral Lord Howe on being appointed his flag captain aboard the Queen Charlotte 100 during the Spanish Armament, and by October he had assumed the role of captain of the fleet with Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian replacing him as the flag-captain. This temporary elevation to the seniority of a rear-admiral was met with remonstrations from many officers of that rank, and a memorial was gathered by them for presentation to the King. Shortly afterwards, on 11 December, Curtis was appointed to the Brunswick 74 which he ensured to man with a choice crew, even going to the extreme lengths of posting himself on the London Road near his estate of Gatcombe in Portsmouth and offering food and grog to anyone of promise. The Brunswick remained in commission during the Russian Armament of 1791 until she was paid off at the end of August, and she was then immediately recomissioned under Curtis’ command as a Portsmouth guardship, where in 1792 he sat on the court-martial of the Bounty mutineers.

He remained with the Brunswick into 1793 before joining Howe once more as captain of the Channel fleet at the outbreak of war in February, serving aboard the Queen Charlotte 100, and participating in the disappointing cruise of July-August, following which he set out for the Admiralty in London to explain the fleet’s early return. He was also present in the October-December cruise, at the end of which he travelled to London with Howe. Earlier, in April of the same year, he had been appointed a colonel of marines.

As a result of Lord Howe’s near collapse during the final stages of the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794, Curtis was responsible for many of the decisions pertaining to the re-forming of the fleet rather than the chase of the French, and for years afterwards he attracted criticism for his caution on the day. Given the honour of delivering the victorious admiral’s despatches to the Admiralty, he arrived at Plymouth on 9 June having come having come home aboard the Phaeton 38, Captain William Bentinck, and in hastening straight for London he imparted as little information as he could get away with, although his evident happiness conveyed a momentous victory. He arrived at the Admiralty on the following evening having had the post boys drive the horses so hard that his post-chaise had twice overturned, resulting in both of his arms being placed in slings. There was much disquiet over his role in the compilation of the despatches which notoriously praised some officers to the detriment to others, but the King was overjoyed with the victory and he celebrated by throwing a gold chain around Curtis’ neck after greeting him at Spithead, and declaring that it should remain in his family forever as a mark of esteem from the Royal family.

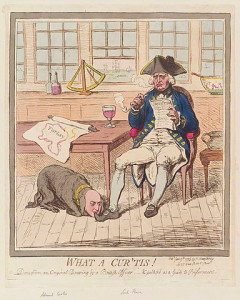

The famous cartoonist James Gilray’s take on the relationship between Lord Howe and Curtis

On 4 July 1794 Curtis was promoted rear-admiral, raising his flag aboard the Queen Charlotte days later during the absence of Lord Howe, and in August he was created a baronet, by which time he had reverted to the role of captain of the fleet to the recuperated Howe. In the early spring of 1795 he flew his flag once more aboard the poorly disciplined and mutinous Queen Charlotte when the commander-in-chief was again indisposed, and in May he represented the sickly Howe as the prosecutor of Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy, conversant with that officer’s conduct at the Battle of the Glorious First of June. Consequently, he was not aboard the Queen Charlotte when she fought at the Battle of Groix on 23 June.

Returning to duty, Curtis shifted his flag in early August 1795 from the Queen Charlotte to the Canada 74, Captain George Bowen, and he received aboard members of the French Royal family including the Comte d’Artois that month at Spithead. In September he removed to the Powerful 74, Captain William O’Brien Drury, and on 18 October at Portsmouth to the Invincible 74, Captain William Cayley.

In January 1796 Curtis briefly had his flag aboard the Prince George 90, Captain James Bowen, before transferring back to the Queen Charlotte. He was a member of the court-martial that sat on 7 April to consider charges against Vice-Admiral Hon William Cornwallis regarding his refusal to shift his flag into a frigate in order to take up his posting in the Leeward Islands. In May he arrived at Portsmouth from London to put to sea from Spithead on the 20th with his flag aboard the Formidable 90, Acting-Captain George Murray, and in command of one of the three divisions of the Channel fleet consisting of four other sail of the line and two frigates he sailed to Cape Finisterre before returning to Portsmouth in June. He then put to sea again with his squadron in August to look out for the homeward-bound Jamaica fleet.

On 20 October he raised his flag aboard the Prince 98, Captain Thomas Larcom, who would remain with him on that ship for three years, and after cruising at sea and then returning to Torbay he was sent to intercept Rear-Admiral Josef de Richery’s squadron on its return from the raids on the Newfoundland fisheries, which had commenced in August. For a short while he paraded off Rochefort, but having sailed for England on 3 November he missed the arrival of de Richery at that port two day later. This misfortune was compounded when following the French breakout and expedition to Ireland in December he was criticised along with his contemporaries, Admiral Lord Bridport and Vice-Admiral John Colpoys, for failing to bring the enemy to battle.

In early April 1797 Curtis put to sea from Portsmouth with nine sail of the line to cruise off the west coast of Ireland and Brest whilst Bridport stayed in home waters with the remainder of the Channel fleet, but by the time he got back to Torbay the great mutiny had erupted on 16 April. His division joined the rebellion and carried their ships into Spithead where the men turned their officers ashore. Curtis was briefly imprisoned aboard his flagship and only released when his old mentor, Admiral Lord Howe, toured the mutinous ships with the chief delegates.

Once his division of six sail of the line returned to duty, Curtis was ordered to join Admiral Adam Duncan’s blockade off the Texel in the first week of June as the mutinies on the North Sea station and at the Nore were still depriving that officer of all but two of his sail of the line. He returned to Portsmouth in early August, but on 13 October sailed once more with several sail of the line from Portsmouth to rejoin Duncan. By this time however the Battle of Camperdown had been won against the Dutch two days previously and thus his reinforcement was no longer required.

By the end of October 1797 Curtis’ squadron was back at St. Helens, preparatory to sailing for Plymouth to rejoin Admiral Lord Bridport and the Channel Fleet, and after cruising off Brest and Ireland in November it anchored in the safe haven of Torbay at the end of the month. On 4 December the division put to sea once more but had to put into Spithead within days after incurring storm damage, and this allowed Curtis to travel up to London to attend the Service of Thanksgiving at St. Paul’s where the captured colours of the fleets of France, Spain and the Netherlands were celebrated.

Curtis returned to Portsmouth on Boxing Day 1797, and on the following 15 January, with his flag still flying on the Prince, he dropped down to St. Helens prior to going out with a small squadron under the orders of Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Thompson, although adverse winds prevented their putting down the Channel. In March he was ordered to take command of a squadron of half a dozen sail of the line and remain at anchor in Plymouth Sound to protect the town against a threatened invasion, and on 9 April this force sailed for Ireland to arrive off Cork four days with instructions to guard the Western Approaches.

At the beginning of June 1798 Curtis’ squadron, now numbering eight sail of the line, reinforced Admiral Lord St. Vincent off Cadiz following the dispatch of Rear-Admiral Lord Nelson into the Mediterranean to monitor the movement of the Toulon fleet, a detachment that would eventually culminate with his victory at the Battle of the Nile on 1 August. One of Curtis first acts as a subordinate to St. Vincent was to preside over the court martial on 12 June of Captain Lord Henry Paulet, who was sentenced to be dismissed the service for striking a lieutenant aboard his command, the Thalia 36. Curtis remained with the squadron of fifteen or so sail of the line off Cadiz for the rest of the year whilst Nelson roamed the Mediterranean, and in November he took command when St. Vincent retired to Gibraltar for a few weeks on the advice of his physician. Curtis himself eventually left Gibraltar on 4 January 1799, and with his flag still aboard the Prince returned to Portsmouth with a small convoy, whereupon he travelled up to London to be presented to the King.

After being promoted vice-admiral on 14 February 1799 Curtis was appointed commander-in-chief at the Cape in the following month in succession to the late Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Cloberry Christian and his temporary replacement, Captain George Losack. Prior to sailing he presided over the court martial on 14 May aboard the Gladiator 44 in Portsmouth Harbour that sentenced Captain Lord Augustus Fitzroy of the sloop Sphinx to be dismissed his ship for not bringing home the East India trade from St. Helena. There was a further delay in August when Curtis was ordered to shift his flag from the Lancaster 64, Captain Thomas Larcom, to the Juste 80, Captain Sir Henry Trollope, whilst all the stores destined for the Cape aboard the former vessel were removed and both ships were ordered around to Torbay.

Eventually receiving sailing orders at the end of August and giving passage to the new governor of the Cape Colony, Sir George Yonge, the Lancaster with a large convoy and several men-of-war was off Cape Finisterre by 19 September and reached the Cape in December. Curtis shifted his flag into the Jupiter 50, Captain Losack, in November 1800, then briefly to the Adamant 50, Captain William Hotham, in 1801, and with the Hon. Duncombe Pleydell Bouverie serving some time as his flag-lieutenant. During his time in command he created a precedent by refitting one of his capital ships, the Jupiter 50, at the Cape, rather than sending her to India. On a personal level there was sadness when his elder son and namesake died at the Hotwells, Bristol in July 1802 of an unknown disorder, two months after returning from the Cape, whilst Curtis’s own health was so fragile that by the beginning of 1803 there was an expectation that he would return home. This became a formality on 21 February when the colony was returned to Dutch control after the Concorde 36, Captain John Wood, had arrived with orders for the British evacuation of the colony.

On 27 May 1803 Curtis, whose health was by now happily restored, returned to Portsmouth aboard the Diomede 50, to which he and Captain Larcom had exchanged, and with a small squadron from the Cape in company, having put into Lisbon in passage. Upon reaching the Channel he learned that war had broken out once more with France, a fact that the squadron immediately celebrated by capturing a rich French East Indiaman off the Isle of Wight bound from the Isle de France to Flushing. Shortly afterwards he struck his flag and travelled up to London to attend the Admiralty.

Despite suggestions that he would imminently be found employment Curtis remained inactive for the next eighteen months. On 23 April 1804 he was advanced to the rank of admiral, and in January of the following year was appointed to a commission charged with revising the civil affairs of the navy with, amongst others, Vice-Admiral James Gambier. He remained with the board until the end of 1808, and during this period the two senior naval officers made several blunders including the ‘restoration’ of the rank of admiral of the red to the navy, a rank that had never existed. In the meantime, Curtis had officiated at Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson’s funeral on 9 January 1806.

On 28 January 1809 he hoisted his flag aboard the Royal William 84, Captain Hon. Courtenay Boyle, as the commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, with Captain John Irwin assuming the command of the flagship from April, and Captain Robert Hall as his flag-captain from April 1810. Following the Basque Roads fiasco of 11 April 1809 Curtis was president of the court martials on Rear-Admiral Eliab Harvey from 22 May aboard the Gladiator 44 in Portsmouth Harbour, and on Admiral Lord Gambier from 25 July, also aboard the Gladiator. As Gambier was not only a lifelong friend but of a similar cautious disposition Curtis was bound to side with him, and the court martial proved to be a whitewash of the admiral’s conduct. On 28 April 1812 Curtis struck his flag upon being superseded at Portsmouth.

In 1815 Curtis was created a G.C.B., and he died at his residence of Gatcombe House, Portsea on 14 November 1816.

On 12 December 1778 Curtis married Sarah Brady, an heiress of Gatcombe House, which residence he acquired with her. They had a daughter, Jane, and two sons, one of whom, Roger, died as a post captain in 1801 and the other, Sir Lucius Curtis, succeeded him as the second baronet and died as admiral of the fleet in 1869.

A favourite of both Admiral Earl Howe and Admiral Hon. Samuel Barrington, a protégé in the early part of his career of the Duke of Cumberland, and a friend of Gambier, Curtis was also admired by Admiral the Earl of St. Vincent and was friendly with the discredited Captain Anthony Molloy. He was unpopular within the fleet however, and many attributed some of Lord Howe’s unfortunate errors to him. The normally reticent Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood described him as ‘an artful sneaking creature, whose frowning, insinuating manners creep into the confidence of whoever he attacks, and whose rapacity would grasp all honours and profits that come within his view.’ Collingwood, it should be recorded, bore a grudge because Curtis appeared to indicate that everything worthy at the Battle of the Glorious First of June had been achieved by the Queen Charlotte.

He was undoubtedly pompous and arrogant, but was also shrewd and courteous where necessary, and even fancied himself attractive to the market girls with whom he frequently bantered. Many had great difficulty in reconciling the bold defender of Gibraltar with the pernickety, cautious fleet manager in Curtis. He could unjustifiably react negatively to his fellow officers and was jealous of Lord Howe’s favourites, such as Captain Robert Barlow. When commanding the Brilliant he was reported to be popular with his officers and crew, and whilst commander-in-chief at the Cape he was praised for his attention to the sick.