Admiral Richery’s recapture of the Censeur – 7 October 1795

On 24 September, the Censeur 74, Captain John Gore, which had been captured from the French at the Battle of Genoa six months previously, departed Gibraltar Bay with an easterly wind in the company of the Fortitude 74, Commodore Thomas Taylor, Bedford 74, Captain Augustus Montgomery, Argo 44, Captain Richard Rundle Burges, Juno 32, Captain Lord Amelius Beauclerk, Lutine 32, Acting Captain William Haggit, and fireship Tisiphone, Commander Joseph Turner. This force was escorting a Levantine convoy variously reported to consist of sixty-three to sixty-nine ships bound for England, although that night, once it had passed through the Straits of Gibraltar, the Juno and Argo parted company with thirty-two of the convoy.

With few resources available at Gibraltar to make good the damage that she had sustained during the Battle of Genoa, the Censeur’s stump of a mainmast had temporarily been fished with a frigate’s mainmast. Similarly, she had been allocated a hotchpotch of a crew, with five men from every ship in the Mediterranean Fleet being supplemented by forty men from the Argo and Juno, together with seven extra lieutenants, every one of them an invalid, and all the sick from the fleet. There were no marines on board.

Although the French were aware of the forming of the Levantine convoy, their intelligence had indicated a much later sailing date, and it was not until the end of September that Vice-Admiral Pierre Martin despatched a squadron from Toulon to intercept it. Commanded by the active and enterprising Commodore Honoré Ganteaume, this force consisted of the Mont Blanc 74, Junon 40, Justice 40, Artémise 36, Sérieuse 36, Badine 28, and Hasard 16. Unsurprisingly, Ganteaume failed to find the convoy, as by this time it was well out into the Atlantic under Commodore Taylor’s escort, but he would go on to enjoy a profitable cruise in the Aegean Sea, during which he released two frigates and a corvette that had been blockaded in Smyrna by the Aigle 38, Captain Samuel Hood, and the Cyclops 28, Captain William Hotham.

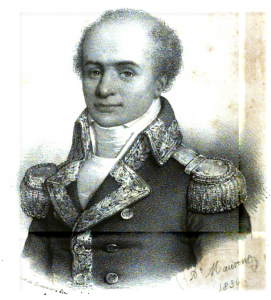

On 6 October, being about one hundred and fifty miles to the north-west of Cape St. Vincent, the Censeur, which despite her deficiencies was a fast-sailing ship, was detached by Commodore Taylor to chase off a French frigate that had been dogging the convoy for several days. Despite being recalled, she was still some way to leeward of her consorts when daylight the next morning revealed six sail of the line and three frigates in the north-east, standing towards the convoy with all sail set on a favourable north-westerly wind. These ships would prove to be another French squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral Joseph de Richery, an officer from Provence who had been discredited and expelled during the days of The Terror but had since been reinstated to the Republican Navy.

Richery’s squadron had left Toulon on 14 September, a fortnight prior to Ganteaume’s departure, with orders to land troops on Saint-Domingue, harry the British shipping off Jamaica, and then cruise off Newfoundland before sailing for Brest to reinforce the reduced fleet there. The force consisted of the Victoire 80, Jupiter 74, Du Barras 74, Berwick, 74, Duquesne 74 and Révolution 74, plus the frigates Embuscade 32, Félicité 32, and Friponne 32. Upon learning of Richery’s sailing, the commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral William Hotham, dispatched Rear-Admiral Robert Man in pursuit with the Windsor Castle 98, Cumberland 74, Audacious 74, Defence 74, Saturn 74, Terrible 74, and frigates Blonde 32, and Castor 32. However, as this detachment was made some three weeks after Richery had left Toulon, the French admiral’s mission was never really in any jeopardy, and it was to his immense good fortune that he had now fallen in, by chance, with the rich Levantine convoy.

Upon sighting Richery’s squadron, Commodore Taylor gave the signal for the convoy to scatter, although his subsequent dispatch would suggest that many failed to do so promptly. Shortly after ten a.m. he signalled his desire to form a line of battle on a south-easterly course with his flagship, the Bedford, and the Censeur, the latter of which was still trying to regain company. Meanwhile, the French frigates headed for the convoy, and within the hour were able to force their way in amongst it, whereupon several vessels immediately struck.

At 1 p.m., just after the British line had finally managed to form, the Censeur’s fore-topmast went by the board, thereby severely retarding her sailing ability. Commodore Taylor consulted with his own officers and Captain Montgomery of the Bedford, and it was concluded that the remainder of the outnumbered British squadron had no alternative but to retreat with all sail set. In order to provide what support they could to the abandoned Censeur, both Taylor and Montgomery ordered stern sections of their own ships cut away so as to allow guns to be hauled aft and trained on their pursuers. The commodore also instructed the Lutine to take the Censeur in tow, but this would prove to be impossible due to the intensity of the enemy ships of the line’s fire as they began to close in, and when she came under fire herself, which she gamely returned, the frigate had to set sail in order that she would be spared the Censeur’s inevitable fate of capture.

Left to his own devices, Captain Gore put the Censeur before the wind, but by 1.50 his command had been overhauled by the Du Barras and a half-hour’s determined action ensued, during which the Censeur’s broadsides were supplemented by the sternchasers of both the Fortitude and the Bedford. It would later be claimed by one of Gore’s biographers, James Ralfe, that the French ship was beaten off with nearly a hundred and fifty casualties, although given the Censeur’s inferiority this casualty rate appears somewhat unlikely. Similarly, Ralfe would claim that when a French frigate had the effrontery to engage the Censeur, she too was served in much the same manner, receiving three broadsides which caused a great deal of damage and forced her to drop astern. Another unsubstantiated claim stated that one of the French sail of the line managed to get up with the Fortitude and Bedford and engage them before apparently losing her main and mizzen masts, but again this report seems unlikely.

The Censeur’s bold resistance eventually persuaded Richery to abandon the pursuit of the other British men-of-war, and after hauling his wind he concentrated on sweeping up the remainder of the convoy and forcing the surrender of the ex-French vessel. Two ships of the line were posted on either quarter of Gore’s command and another raked her from astern, yet the Censeur put up a stout defence, in the course of which her remaining topmasts went by the board and she suffered much damage to her rigging. With his stock of powder limited, Gore determined to go down fighting, and putting his helm a-starboard he attempted to drive his ship, which was now apparently on fire in several places, across the hawse of the Formidable 84, which according to Ralfe had been firing red-hot shot. In this attempt Gore failed, and having no other option left to him he eventually surrendered at 2.30.

In addition to the Censeur, it has been reported by most eminent historians that all but one of the convoy of thirty-one merchantmen were taken; however, it would seem that a small number did in fact make good their escape. The first survivor to reach home was the fast-sailing Justina, which arrived at Portsmouth on 15 October with news of the French attack and the loss of the Censeur and several merchantmen. Such was the gravity of her tidings that a messenger was sent post haste to recall to London the first lord of the Admiralty, Earl Spencer, from his estate at Althorp in Northamptonshire. A second survivor, the Constantine, reached Torbay shortly afterwards to confirm the Censeur’s capture, whilst on the 17th, Taylor’s men-of-war and two merchantmen arrived at Portsmouth and Captain Burges of the Argo brought his convoy of thirty-two ships into the Solent. The next morning at 1 a.m., Commodore Taylor reached the Admiralty from Spithead in person, having received leave to go to town by Admiral Sir Peter Parker, the commander-in-chief at Portsmouth. As the news of the disaster continued to break, commercial losses were estimated to be in the region of three million pounds, but there was at least some relief that Burges’ convoy had got through, not least amongst the silk weavers in Spitalfields who would have been thrown out of employment had their raw materials not been received.

Together with his prizes Richery had already entered Cadiz on 13 October, but in line with the laws of neutrality he was required to transfer all but three of his ships up the coast to Rota. The French admiral appears to have been mightily impressed by Gore’s tenacious defence and the latter’s immediate exchange was arranged with the captain of the Modeste 36, whose frigate had been captured at Genoa on 5 October 1793 by the Bedford, Captain Robert Man, resulting in a long confinement for the French officer at Gibraltar. One of the captured merchantmen, the Golden Lion, was also released by Richery to facilitate the voyage home on parole of the Censeur’s officers and invalids, who were to be exchanged with a similar number of French prisoners, and Richery then allowed the remainder of the crew to proceed to Gibraltar under the same conditions on board a transport commanded by the Censeur’s second lieutenant, Robert Clephane. According to James Ralfe, the men would eventually seize command of the ship from Clephane, and after sailing for England would drive her ashore on Hartland Point on the north-western coast of Devon before deserting. Following his own arrival at Portsmouth aboard a cartel at the beginning of December, Gore was tried and acquitted by court martial for the loss of the Censeur, receiving high praise from the president of the court, Rear-Admiral Sir Roger Curtis, for the manner of his defence.

One consequence of the Censeur’s resistance was that it temporarily prevented Richery’s mission to Newfoundland, and after he was blockaded in Cadiz by Rear-Admiral Man it would be another ten months before the French admiral got away for Newfoundland. This occurred when he put to sea with the Spanish fleet following the Treaty of San Ildenfonso and Man’s recall by the new commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, Admiral Sir John Jervis.

Meanwhile following his successful cruise in the eastern Mediterranean, Commodore Ganteaume had begun retiring towards France under the pursuit of a British squadron led by the redoubtable Captain Thomas Troubridge, and consisting of that officer’s Culloden 74, the Diadem 64, Inconstant 36, Flora 36, and Lowestoft 32. Over the Christmas period the British closed in, and to evade capture Ganteaume detached the smaller Badine to lull the British away towards Cape Matapan on the Greek Archipelago. The Badine eventually sailed into the Gulf of Coron where she remained under the blockade of the Lowestoft, Captain Robert Plampin, whilst the rest of the French squadron finally reached Toulon on 5 February 1796.