Unicorn, Santa Margarita, Dryad v Tribune, Tamise, Proserpine – June 1796

On 19 May the British frigates Unicorn 32, Captain Thomas Williams, and Santa Margarita 36, Captain Thomas Byam Martin, together with the sloop Hazard under the command of a Lieutenant Parker, departed their base at Cork on a cruise. Learning the next day that there was a French privateer lurking off the south-west coast of Ireland, Captain Williams dispatched the Hazard to patrol between Cape Clear and the Shannon whilst he remained with the two frigates off the Cape. However, news received several days later that the Hazard had retaken two prizes and chased the privateer off allowed the two frigates to proceed on their cruise.

On the evening of 7 June, the frigates took possession of a valuable Swedish ship transporting Dutch property from Surinam, and the Unicorn’s third lieutenant, John Cook Carpenter, was instructed to take her into port. At dawn the next day, sailing some fifty miles to the west of the Scilly Isles, the Santa Margarita discovered three strange sails a couple of miles away on her lee bow, and having signalled their presence to the Unicorn, the two British frigates gave chase. At 9 a.m., whilst still exhibiting an intention of escaping their pursuers, the strangers formed themselves into a bow and quarter line, although it was evident that the largest vessel was under a reduced sail in order to maintain station with her consorts.

Once he was able to ascertain the strength of the squadron from his advanced position ahead of the Unicorn, Captain Martin was ordered to come within hail of Captain Williams, and it was resolved that the former would attack the smaller frigate, which Martin had identified as the ex-British Thames, whilst Williams would take the Unicorn into battle with the larger vessel. Their prey would prove to be a raiding squadron under the command of the American -born Commodore Jean Moultson of the Tribune 32, an officer of sixteen years seniority in the French Navy. In company were the Tamise 32, Captain Jean Baptiste Alexis Fradin, and a corvette, the Légère 18, Lieutenant Jean Martin Michel Carpentier. Another frigate, the Proserpine 40, Captain Etienne Pévrieu, had lost contact in heavy fog with the squadron shortly after it had come out of Brest on 6 June.

The Unicorn had been launched in July 1994 and carried twenty-six 18-pounder cannons on her upper gun deck in addition to six 6-pounder cannons and six 32-pounder carronades on her quarterdeck and forecastle, giving her a broadside weight of metal of three hundred and forty-eight pounds. She had a crew at the time of two hundred and forty men, and her 34-year-old commander, Thomas Williams, the son of a naval captain who had died from his wounds in the American Revolutionary War, had been one of those officers posted captain at the end of the Spanish Armament in 1790.

The Unicorn’s consort, the Santa Margarita, had been captured by the Romney 50, Captain Roddam Home, from the Spanish in November 1779, just nine months after being commissioned. She carried twenty-six 12-pounder cannons on her upper gun deck, ten 6-pounder cannons on her quarterdeck and forecastle, and four 32-pounder carronades on her quarterdeck, giving her a broadside weight of metal of two hundred and fifty pounds. Her crew numbered two hundred and thirty-seven men and her commander, 22-year-old Thomas Byam Martin, a son of the late and influential comptroller of the navy, Sir Henry Martin, was a post captain of two and a half years seniority.

On the French side, the fast-sailing Tribune had been in service for two and a half years and had adopted her revolutionary name instead of the original ‘Charente Inférieure’ in 1794. She reportedly had an armament of twenty-six 12-pounder cannons on her gun deck and sixteen 6-pounder and 42-pound carronades on her quarterdeck, with a contemporary historian calculating her broadside weight of metal to be only two hundred and sixty pounds. Her crew numbered three hundred and thirty-seven men. The Tamise had originally been commissioned into the British Navy in 1758 and a year later, whilst under the command of Captain Stephen Colby, had captured the French frigate Arèthuse 32. She had later seen service in the American Revolutionary War before being paid off in 1781. After being recommissioned in 1793, she had been captured by Captain Zacharie Jacques Théodore Allemand’s squadron on 4 October and renamed ‘Tamise’. With a crew of three hundred and six men, she probably carried twenty-six 12-pounder cannons on her gun deck, six 6-pounder cannons on her quarterdeck and forecastle, and six 36-pound carronades, giving her a broadside weight of metal of approximately two hundred and eighty-two pounds.

By 11.30 the Santa Margarita was in range of the enemy, but with the French closing up in mutual support, Captain Martin wisely decided to await his superior officer before engaging. At 1 p.m. the French vessels hoisted their colours, and with the Unicorn coming up on the Santa Margarita’s weather beam a running fight ensued. Over the next two hours the two French frigates, with the Tribune evidently retarded by the slower Tamise, attempted to disable their pursuers by yawing and firing broadsides, and in making good practice they were able to slow the British approach, despite the fire of the latter’s bow chasers. By now, the dull-sailing Légère had already hauled out of the line to windward with the apparent intention of assisting either of her consorts as was deemed appropriate. Shortly afterwards she brought to, and ignoring her consorts to the surprise of the British, she took the opportunity to board a sloop that had been passing by on the opposite tack.

At 4.15 p.m. the straggling Tamise threw her helm a-larboard to avoid the Unicorn’s fire and attempted to give the ever-encroaching Santa Margarita a raking broadside. Martin skilfully avoided the manoeuvre, ran his frigate alongside at pistol-shot range, and over the next twenty minutes bombarded the Frenchman into submission. During this action the British frigate suffered casualties of two men killed and three wounded against the French losses of thirty-two men killed and nineteen wounded, many of whom would become fatalities.

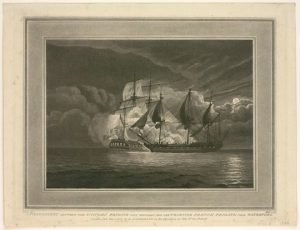

Meanwhile, the Unicorn had been attempting to get to grips with the Tribune, which in turn was endeavouring to make good her escape. Over the next ten hours the two ships raced northwards towards the St. George’s Channel, passed Tuskar Rock off the south-east coast of County Wexford, and stood up the Irish Sea. During this pursuit the Unicorn suffered damaged aloft and to her maintop-sail, but with the wind abating on the onset of darkness, and having covered some two hundred and ten miles, she finally succeeded in taking her enemy’s wind and laying alongside her at 10.30. The Unicorn’s crew gave three cheers and a thirty-five-minute cannonade followed, with the French frigate losing her fore, main, and mizzen topmasts. Even so, the Tribune refused to accept defeat, and under the cover of the smoke she attempted to drop below the Unicorn’s quarter and cross her stern to effect a raking broadside and gain the weather-gauge. Instantly Williams threw his sails aback, his frigate gathered sternway across the Tribune’s bow, and the Unicorn regained her former station from where her fire enabled her to enforce the French surrender. Although she had been well handled, the French frigate had failed to inflict a single casualty aboard the Unicorn, whilst suffering thirty-seven men dead and fifteen wounded herself, including Commodore Moulston.

Whilst these two actions had been in progress, the Proserpine had been searching for her consorts, but at 1 a.m. on 13 June, some thirty-five miles to the south-east of Cape Clear, Captain Pévrieu’s frigate fell in with another of the Irish station’s cruisers, the Dryad 36, Captain Lord Amelius Beauclerk. Initially, the Proserpine stood towards the British frigate from the southward with the wind at north north-west and the British frigate on the starboard tack, but upon realising that the other vessel was not one of Commodore Moulston’s squadron she hauled her wind and tacked away.

The Dryad had been launched just a year previously and had an armament of twenty-six 18-pounder cannons on her upper gun deck, together with ten 9-pounder cannons and eight 32-pounder carronades on her quarterdeck and forecastle, giving her a broadside weight of metal of four hundred and seven pounds Her crew numbered two hundred and fifty-one men, and her commander, Lord Beauclerk, was the somewhat eccentric 25-year-old son of the Duke of St. Albans and a post captain of nearly three years seniority.

The Proserpine had been launched ten years previously and she reportedly carried twenty-six 18-pounder cannons on her upper gun deck in addition to ten eight-pounder cannons and four 32-pound carronades on her quarterdeck and forecastle, giving her a broadside weight of metal equivalent to three hundred and seventy-three British pounds. Her crew numbered three hundred and forty-eight men.

Once their identities had been confirmed, a long chase developed with both frigates hoisting their colours shortly after 8 a.m. and the Proserpine causing some damage aloft to her pursuer through the proficient use of her stern-chasers. However, by 9 a.m. the Dryad was able to run alongside her opponent and begin hammering shot into her larboard hull, resulting in the French frigate hauling down her colours within forty-five minutes of coming to close action. Neither vessel lost a spar in the engagement, although the Dryad suffered more damage to her rigging and sails than the Proserpine because of her enemy’s usual practice of firing high to attempt the disabling of her opponent. During the action the Proserpine suffered casualties of thirty men dead and forty-five wounded as opposed to two men dead and seven wounded on the British side.

As for the Légère, she made good her escape for the present, but she was finally run down on 22 June by the frigates Apollo 38, Captain John Manley, and the Doris 36, Captain Hon. Charles Jones.

Captain Williams’ letter to his superior, Vice-Admiral Robert Kingsmill, dated 10 June from a position some twenty miles to the north-west of Holyhead, praised his officers as was the custom, but also paid tribute to the purser, Mr Collier, who in the absence of Lieutenant Carpenter had taken on that officer’s responsibilities. Four days later the Unicorn and her prize arrived at Cork. Meanwhile, Captain Martin, who had taken his prize into Cork on 12 June, acknowledged the assistance of a volunteer, Commander Joseph Bullen, in his dispatch dated the day before at sea, as that officer had been of valuable assistance with the main deck guns. As the senior captain, Williams was later knighted for his victory, whilst Lieutenants George Harrison of the Santa Margarita, Thomas Palmer of the Unicorn, and Edward Durnford King of the Dryad were promoted for their part in the captures.

There was a sad postscript to the capture of the Tribune when two years later, on 16 November 1797, she sank with the loss of all but seven of her crew off Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her erstwhile consort, the Thames, re-entered the British Navy in December 1796 and in the following summer sailed for Jamaica. After returning to European waters, she took a couple of French corvettes and also participated in the second stage of the Battle of Algeciras in 1801 before being broken up two years later. The Proserpine was added to the Navy as the Amelia and commissioned in August 1797, seeing a great many actions until she was broken up in 1816, and the Légère was added to the fleet under her own name before going out to Jamaica in 1798 and ending her career three years later.

With regard to the victorious British frigates, the Unicorn remained in service until the end of the Napoleonic War in 1814, and the Santa Margarita’s was sold by the Navy in 1836, although her career had effectively ended in 1807 when her last post captain had left her. The Dryad remained in service until the end of the Napoleonic War and then survived in various guises until finally being broken up in 1860. All three frigates were prolific in their captures of enemy privateers during the French wars without ever enjoying the opportunities of glory that had presented themselves in June 1796.

A Purser acting as a fighting officer was unusual. Not trained for such.