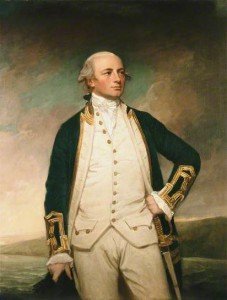

William Peere Williams-Freeman

1742-1832. He was born on 6 January 1742 in the Episcopal Palace at Peterborough, the son of the Rev. Dr Frederick Williams, prebendary of Peterborough, and the grandson of William Peere Williams, a politician and law reporter of repute. His mother, Mary Clavering, was the daughter of the Bishop of Peterborough, and he became the uncle of Admiral Christopher Nesham.

After attending schools at Stamford and Eton, Williams was educated at the Royal Naval Academy in Portsmouth from 1757 whilst his name was included on the books of the Royal Sovereign 100. He first went to sea in August 1759 aboard the Magnanime 74, Captain Lord Howe, in which he was present at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in November. Remaining with Howe until the peace of 1763, he served briefly in the Princess Amelia 80 during the summer of 1762 when that officer became flag captain to Rear-Admiral Prince Edward, the Duke of York.

In August 1763 he joined the Romney 50, Captain Lord Colville, in which he served on the Halifax station, and upon being promoted lieutenant on 18 September 1764, he moved to the Rainbow 44, Captain Walter Stirling, which was employed in North American waters and returned to England in October 1766.

Williams was promoted commander of the bomb-ketch Thunder on 26 May 1768, although it is not clear that he ever took her to sea, and he was posted captain on 10 January 1771, of the Renown 30 for purposes of rank only, being one of fourteen officers, including his namesake William Williams, who were advanced at this time.

William Peere Williams

After being appointed to the frigate Active 28 in March 1771, he recommissioned her at Sheerness and sailed for the West Indies in September to join Rear-Admiral Robert Man’s squadron. In September 1772 a house in which he and his wife were living was destroyed when a hurricane tore through the islands, and the storm also drove the Active from her moorings in the harbour at Antigua, rendering her mast-less. Having then been taken ill in the Caribbean, Williams obtained a transfer to the Newfoundland station in 1773, but here the harsh climate took such a toll on his fragile health that on 11 October he exchanged into the Lively 20, Captain George Talbot, and returned with that vessel to England to be paid off by the commissioner at Portsmouth on 6 December.

By March 1777 Williams was fit enough to serve again, and he was appointed to the swift-sailing frigate Venus 36 at Portsmouth, which put out of the harbour for Spithead on 2 August. After a long wait for final orders, she set sail for New York on 29 August carrying two hundred thousand guineas for the Army, and with a convoy of victuallers and storeships. Unfortunately, she was then detained for almost three weeks in the Cowes Roads by a change in the wind which prevented her passing through the Needles, and she was obliged to return to St. Helens. The delay in her departure was described as a great disappointment to the Government.

Having eventually reached North America, the Venus was present at the defence of New York in July 1778 and in the action with the French fleet during the relief of Rhode Island in August. Williams exchanged on 18 September with Captain James Ferguson into the Brune 32, and his new command departed New York for England on 18 October with the peace commissioners and a convoy of sixty vessels, whilst the Venus sailed south with Commodore William Hotham’s squadron to reinforce the Leeward Islands. The Brune eventually arrived at Portsmouth on 21 December after what was described as a tedious voyage for a ship that was as worn-out as her predominately Scottish crew, and shortly afterwards she sailed for the Thames to be paid off.

At Deptford in April 1780, Williams commissioned the impressive and heavily armed new frigate Flora 36, which was fitted with carronades in an experiment that was undertaken to see whether the short-range weapons should be established on all other ships of her rate. In July it was reported that she was to go out to the Lisbon station, and on 5 August she arrived at Portsmouth from the Downs. Just five days later, on 10 August, and a bare three months after her launch, she captured the French frigate Nymphe 32 off Ushant, with her excellent first lieutenant, Edward Thornbrough, leading the boarding party. Putting into Falmouth before eventually reaching Portsmouth, the Flora and her prize were ordered to be fitted out for immediate service, and by 22 September Williams’ command was out of dock. Unfortunately, within a month she was back at Portsmouth having sprung her foremast, but she then put out to join the Grand Fleet, and when she returned to Portsmouth on 1 January 1781, it was having taken several prizes despite being chased into Cork by two frigates from the Comte d’Estaing’s squadron.

On 20 January 1781 the Flora sailed from Portsmouth for the North Sea, but she had to put back to Spithead through rough weather which had caused her to lose an anchor and cable. On 23 March she arrived at Cove in Ireland, and she afterwards served in Vice-Admiral George Darby’s relief of Gibraltar on 12 April.

Next being despatched with thirteen supply ships to Minorca, and being in company with the Crescent 28, Captain Hon. Thomas Pakenham, the Flora fell in with a Spanish squadron near Gibraltar on 23 May. Faced with overwhelming odds the British frigates fled, and with Williams providing valuable support to his slower consort they lost their pursuers overnight and got into Gibraltar on the 29th. Having appraised the governor of the Spanish presence, the Flora and Crescent were then sent out in search of two Dutch frigates and brought them to action the next day. After a ferocious two-and-a-half-hour engagement, later recounted as the bloodiest in the previous twenty-five years, Williams forced the surrender of the Castor 36, sustaining forty-one casualties in the process, and he then re-took the Crescent which had struck her colours to the other Dutchman, the Briel 36. Unfortunately, after driving the Breil off and getting all three ships into some state of repair, Williams had the mortification to lose the Castor and Crescent to the French frigates Friponne 32 and Gloire 32 on 19 June. Some historians would later claim that he could have achieved a better outcome against the French if he had employed his powerful frigate to the best of her ability. Returning alone to England, the Flora reached Portsmouth on 27 June and shortly afterwards was taken into dock.

On 7 September 1781 the Flora left dock at Portsmouth and a week later sailed for Plymouth. After spending a short time with the Channel Fleet, she reached Cork on 22 October, from where she departed six days later on a cruise; however, in the middle of the following month Williams resigned the command to Captain Samuel Marshall.

Williams did not see any further employment, possibly because his political leanings were unfavourable to the Pitt administration. Instead, he profited on land through his rich connections which saw him inherit the estate of Yew House, Hoddesdon, in Hertfordshire in 1784, and which supplemented his ownership of Remenham Manor near Henley-on-Thames. In November 1821 he assumed the additional name of Freeman upon inheriting the estate of Fawley Court near Henley-on-Thames.

In the meantime, he had been promoted rear-admiral on 12 April 1794, vice-admiral on 1 June 1795 and admiral on 1 January 1801, whilst he also served as a justice of the peace in Oxfordshire. He became admiral of the fleet on 28 June 1830 at the instigation of the newly crowned King William IV after the monarch had learned of the death of Williams’ son, and it was his old subordinate, Admiral Sir Edward Thornbrough, who delivered the Lord High Admiral’s baton in a Morocco Case to him.

Williams died at Hoddesdon on 10 February 1832, at which time he was the oldest officer in the Navy. He was interred in the family vault at St. Augustine’s Church, Broxbourne.

He married the wealthy Henrietta Wills at Brixworth, Northamptonshire, on 20 June 1771 and had four children, none of whom survived him. A son, Frederick, died at Edinburgh University aged 18 in 1798, and a further son, William, died in July 1830. His wife died on 3 September 1819 at Hoddesdon. He was succeeded in his estates by two grandsons who had yet to reach their majority.

Williams’ years of unemployment were compensated by the inherited wealth that enabled him to live in great comfort, and to bestow great hospitality and benevolence on his friends and family. He appears to have been in far better health after his enforced retirement than he was before it.