Sir David Milne

1763-1845. He was born on 25 May 1763 at Musselburgh near Edinburgh, the son of David Milne, a silk merchant, and of his wife, Susan Vernor.

After an education in Edinburgh, Milne entered the Navy in May 1779 aboard the Canada 74, Captain Hugh Dalrymple, following whose death the ship was commanded by Captain Sir George Collier. Serving with this vessel, he was present at Vice-Admiral George Darby’s relief of Gibraltar on 12 April 1781 and the capture of the Spanish frigate Santa Leocadia 44 on 1 May. During August the Canada went out to North America under the command of Captain Hon. William Cornwallis with Rear-Admiral Hon. Robert Digby’s reinforcement, and on 25/26 January 1782 she fought at the Battle of St Kitts. Three months later, on 12 April, she fought at the Battle of the Saintes, and she was subsequently attached to Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves’ prize convoy which was devastated by the Central Atlantic Hurricane on 16 September. After eventually reaching England, Milne joined the Elizabeth 74, Captain Robert Kingsmill, which vessel was paid off on 29 March 1783, having previously departed for the East Indies but then returned home due to damage incurred during a storm in the Bay of Biscay.

Following the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783 Milne joined the East India Company, reportedly serving aboard a ship called the General Elliot. It is possible that he rejoined the navy as an able seaman in July 1790 aboard the Eurydice 24, Captain George Lumsdaine, seeing service in the Mediterranean prior to being paid off in December 1791, and his employment over the next two years is also unclear, with some accounts declaring that he spent six weeks aboard a vessel called the Aurora, which could equally have been a merchant vessel or the naval 28-gun frigate, and others that he returned from the East Indies aboard a Company ship in early 1793 to seek re-employment in the Navy.

With the rank of masters’ mate, Milne was accepted onto the Boyne 98, Captain George Grey, the flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir John Jervis, whose expeditionary force to the Leeward Islands began congregating in the autumn of 1793. Rejecting a lieutenancy aboard a storeship to remain with the Boyne, Milne was with the Jervis expedition when it arrived at Barbados on 6 January 1794, and a week later he was promoted lieutenant of the Blanche 38, Captain Christopher Parker, who was succeeded shortly afterwards by Captain Robert Faulknor. Under this brilliant officer he participated in many remarkable actions against the enemy, the highlight of which was the capture of Guadeloupe in the middle of April, when Faulknor led the uphill assault on Fort Fleur d’Épée. Milne also earned personal glory, not least for cutting a vessel out under heavy fire from Mahout Bay, Guadeloupe, and for his cutting-out of an eight-gun schooner on the island of Deseada.

On 4/5 January 1795, Captain Faulknor lost his life in the action that saw the Blanche capture the French frigate Pique 38. Come the conclusion of the engagement, all the Blanche’s boats had been destroyed, leaving Milne to take possession of the defeated vessel by swimming across with ten men and, somewhat curiously, a Newfoundland dog. He was charged by the first lieutenant, Frederick Watkins, with taking news of the victory to the commander-in-chief, Vice-Admiral Benjamin Caldwell, who according to initial reports immediately promoted both Watkins and Milne to the rank of commander. Other sources claim that Milne was at first slighted by having a junior lieutenant imposed above him on the Blanche, on which Captain Charles Sawyer had replaced the late Captain Faulknor, and that it was only after further service with that vessel that he received news at Martinique of his promotion by the Admiralty to the rank of commander on 26 April.

Milne did not immediately join his intended command, the sloop Inspector 14, which at the time was at Tortola in the Virgin Islands, as he was required to act in command of the frigate Quebec 32 following Captain Josias Rogers’ death at Grenada on 24 April 1795. He then transferred to the frigate Alarm 32 when her captain, James Carpenter, exchanged into the Quebec, and whilst commanding the latter vessel he sunk the French corvette Liberté 20 off San Domingo on 30 May, managing to save about one hundred of her crew of one hundred and thirty men from drowning. Eventually joining the Inspector at Tortola, he cruised in protection of the trade before sailing for Martinique. When the Inspector was ordered to England with a convoy, Admiral Sir John Laforey, the new commander-in-chief, prevailed upon Milne to undertake the duties of the superintendent of transports at Martinique, and at the first opportunity he posted him captain to the frigate Matilda 28 on 2 October; however, Milne continued to perform the superintendent’s duty with exemplary professionalism whilst his first lieutenant commanded the Matilda at sea.

In January 1796 Milne was appointed by the Admiralty to the captured Pique 36, which he joined at Barbados. On 9 March he took the French privateer Lacédémonian 14 off that island, and he assisted Captain Thomas Parr in the capture of the Dutch possessions of Demerara and Essequibo on 23 April, and Berbice on 2 May. Shortly afterwards, and in company with two other men-of-war, the Pique shared in the capture of ten Dutch merchantmen off Surinam which were laden with sugar, the prizes being taken to Martinique. Meanwhile, on his own authority and at the request of the settlement’s governor, he escorted the trade from Demerara to St. Kitts, and having found that the European convoys had departed from the latter island, and in lieu of any orders from the new commander-in-chief in the Leeward Islands, Rear-Admiral Henry Harvey, he decided to take his charges all the way back to England rather than risk remaining in the exposed anchorage during the hurricane months. When the Pique arrived at Spithead on 10 October it was without her mizzen mast and foretopmast which had been lost in the voyage home, although this had not prevented her from taking a couple of prizes in the chops of the Channel.

After seeking and gaining Admiralty approval for his conduct, Milne spent some time ashore until the Pique came out of Portsmouth dock at the end of January 1797 and sailed to join the Channel Fleet. She was present at the Spithead mutiny on 16 April, and when her men rebelled once more in the Channel, Milne chased one of the ringleaders and hauled him on deck before seizing another from within the main body of men on the forecastle and dragging him onto the quarterdeck. On the next day he tried to remove the two prisoners into the Atlas 90 prior to trying them by a court-martial, but Captain Matthew Squire refused to take them out of a concern for the reliability of his own men, and after receiving their contrite apologies Milne pardoned the mutineers.

Continuing in the Channel Fleet with frequent returns to Torbay and Plymouth, on 7 September 1797 the Pique came in from Brest with a Prussian prize, and in January 1798 she arrived at the Devonshire port having lost her mainmast. Whilst at Spithead during February, the frigate’s officers and men made a voluntary contribution from their pay to the defence of the country, prior to sailing to reconnoitre Brest. In early May the Pique departed Portsmouth on a cruise, and on 29 June, whilst in the company of the frigates Jason 38, Captain Charles Stirling, and Mermaid 32, Captain James Newman, she came upon the French frigate Seine 40, near the Penmarks. In the fierce engagement that resulted, the Pique, Jason, and Seine, all found themselves ashore before the Mermaid came up and forced the Frenchman’s surrender. Such was the distressed state of the Pique that nothing could be done but set her ablaze, and subsequently Milne and his crew returned to England aboard the Seine. The prize was quickly bought into the Navy, and once he had been exonerated by a court martial for the loss of the Pique, the command of the Seine was given to Milne.

Whilst the Seine was being refitted Milne visited his family in Scotland, and following her commissioning in November 1798, she sailed out of Portsmouth Harbour on 28 December with most of her crew made up of men from the Pique. At the end of January 1799 she sailed to blockade Le Havre, prior to returning to Portsmouth at the end of the month, and in the third week of February she arrived at the Hampshire port with a Batavian East Indiaman under Danish colours which she had captured in the Channel. She continued to operate out of Portsmouth for the rest of the spring and summer, until she departed on 19 October with a convoy and the annual storeship for West Africa, where she patrolled the coast for the next five months before escorting the trade to Barbados.

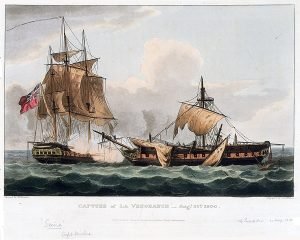

Whilst cruising in the Mona Passage on 20 August 1800, the Seine fell in with the French frigate Vengeance 48, which was under orders to avoid combat and initially tried to make good her escape. An engagement with the Seine which was to prove one of the most ferocious of the war eventually began at midnight, with the two adversaries twice breaking off the action to effect repairs, and the Vengeance only submitting when she had been dismasted and was on the verge of sinking. Milne’s ship suffered casualties of thirteen men killed, including his brother George, who was the second lieutenant, and twenty-nine wounded.

The Seine spent the remainder of the French Revolutionary War in the Gulf of Mexico, in blockade of the Mississippi, or cruising out of Jamaica, during which time, on 19 December 1800, she captured a Spanish brig with 48,000 dollars in her hold. She ultimately returned to Portsmouth on 12 March 1802 with many invalids from Jamaica after a passage of seven weeks in the company of the Apollo 36, Captain Peter Halkett, and she was paid off at Chatham in the following month. Shortly afterwards, Milne travelled to London where he kissed the King’s hand on being presented at a levee.

Although offered a peace time command by the new first lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of St. Vincent, Milne declined on the grounds of his reduced health, and after heading north to Scotland, he attended a grand dinner in Edinburgh given by Henry Dundas during July. Upon the resumption of hostilities with France in 1803 Milne, who somewhat surprisingly had not yet been honoured for any of his frigate captures, was re-appointed to the command of the Seine, and he commissioned her at Chatham in May. Before he could put to sea, he was the defendant in a court case in which Admiral Sir Hyde Parker claimed a share of the prize money that Milne had earned in his capture of the two prizes when returning to England from St. Kitts in October 1796, the premise being that Parker had just arrived on the Leeward Islands station as the new commander-in-chief, and was thus entitled to a share of the money. Milne won the case when the judge, Lord Ellenborough, ruled that as Parker had not given the orders for Milne to return home, he had no grounds on which to make a claim.

In June 1803 the Seine completed her refit at Chatham, and when she was finally ready for sea at the end of the month she was placed under orders of Rear-Admiral Edward Thornbrough in the North Sea. Unhappily, due to pilot error, she drove aground in perfect conditions off the Texel on 21 July and was set on fire to prevent her being stripped by the enemy. After being honourably acquitted at the subsequent court martial at Sheerness on 4 August, which amongst other penalties sentenced the pilots to two years solitary confinement, Milne was unable to gain further employment, perhaps because he had tried to defend the pilots and had made some injudicious comments to the court. With his prospects also bleak following the departure of Lord St. Vincent from the Admiralty, he began investigating how local populations might be utilised to defend the coast, thereby developing the Sea Fencibles.

Retiring to Inveresk in Scotland, Milne married in April 1804 and began raising a family. On 25 July he officiated at a sailing race off Leith involving a contingent of Scottish notables and naval officers, and in the following month he was appointed to command the Sea Fencibles in the Firth of Forth. He returned to court in January 1805 to face Admiral Sir Henry Harvey when that officer made a similar claim to Sir Hyde Parker, in essence that he had been the commander-in-chief in the Leeward Islands at the time that Milne had sailed home from St. Kitts with the convoy in October 1796, and that it was he who was owed the admiral’s share of the prizemoney for the two captures which the Pique had made in the Channel. Again, Milne won the case when it was proved that Harvey had not given the orders for the Pique to return to England.

He remained in command of the Forth Sea Fencibles until appointed to the Impetueux 74 in August 1811 by the new first lord of the Admiralty, Charles Yorke. On 12 September this vessel arrived in the Downs with a squadron from the Baltic, and she then spent time off Flushing before reaching Portsmouth on 18 October. In December she joined the blockade of Cherbourg, and later that month she intercepted five French officers who had broken their parole, stolen a wherry at Portsmouth, and rowed across the Channel.

On 1 March 1812, the Impetueux sailed out with the East India convoy from which she was detached to Lisbon, and by 5 June she was off Madeira in the company of the Niobe 38, Captain James Katon, in an ultimately fruitless search for two French frigates which were said to have captured up to forty British vessels. During the same month, Vice-Admiral George Martin left Portsmouth with Captain Charles Inglis to commandeer the Impetueux as his flagship in in the Tagus, and so Milne vacated the command.

In August 1812 it was announced that Milne would join the new Dublin 74, which was to be commissioned at Sheerness; however, in September he was instead appointed to the Venerable 74 on the north coast of Spain in place of Captain Sir Home Riggs Popham. By making alterations to her stowage, he soon transformed this vessel from one of the slowest ships in the fleet to the fastest. She returned to Portsmouth on 30 December, and in January 1813 at Spithead Milne and a Royal Artillery officer conducted an experiment in the use of a lighter 24-pound cannon. A spell off Cherbourg followed with several returns to Portsmouth, and on 29 July the Venerable sailed from the latter port with specie and reinforcements for the Army in Spain. She was back at Portsmouth by 8 November following a fruitless cruise in the Atlantic in the company of the Horatio 38, Captain Lord George Stuart, which had seen the two vessels sail as far west as the Newfoundland Banks during the previous month.

Having joined the Bulwark 74 in December 1813, Milne sailed with a convoy for Bermuda in February 1814, and he finished off his service in the war with a stint off Boston where, much to his personal regret, he thoroughly halted the local trade with his many captures, although he ensured not to harass any fishing vessels. He left his command on hearing news of his promotion to rear-admiral on 4 June, and he returned home in November from Halifax aboard the frigate Loire 38, Captain Thomas Brown, to learn shortly afterwards of the death of his wife at Bordeaux.

Milne was appointed to the command of the Halifax station in May 1816, and prior to his intended sailing with his flag aboard the Leander 50, Captain Edward Chetham, he attended a levee with the Prince Regent at the beginning of July. Shortly afterwards, he was asked to delay his posting and instead second Admiral Sir Edward Pellew in the expedition against Algiers which aimed to put an end to Christian slavery. Hoisting his flag aboard the Impregnable 98, Captain Edward Brace, he played a prominent part in the Bombardment of Algiers on 27 August when his flagship overshot her allotted position and received over two hundred and thirty-three shot, thereby incurring casualties of fifty men killed and one hundred and sixty wounded. Milne himself escaped severe injury, although he did suffer some lameness after a round shot passed between his legs. He was ordered home with despatches aboard the Leander to arrive at Plymouth on 21 September, prior to reaching the Admiralty three days later. He was created a K.C.B. on 20 September in the honours that were handed out for the successful expedition, and he received further awards from the Netherlands and Naples, together with a gold snuffbox from Pellew, a sword, and the freedom of the City of London.

Milne spent Christmas 1816 in Edinburgh, and during the following month he put his house at Inveresk up for let in order to take on his delayed command of the North American station. After being lauded at various functions in London during January, he hoisted his flag aboard the Leander 50 with Captain Chetham at the beginning of February, but contrary winds delayed his departure until the middle of March, and it was not until 24 April that he arrived at Bermuda. During July he was at Halifax before visiting New Brunswick, but upon returning to Nova Scotia his health saw a decline, and it was with some relief that he departed for Bermuda, as was the custom, that winter. Throughout the early months of 1818 it was reported that he was expected to resign his post on account of his poor health, but the warmer climate of Bermuda restored him, and he resumed his duties at Halifax that summer. Issues with illegal American fishing vessels apart, his tenure was a quiet one, and he returned to Portsmouth aboard the Leander on 10 July 1819 after a three-week voyage from Bermuda. Days later it was reported that he had taken a hotel in Jermyn Street with his two teenage sons, and in September he married his second wife.

Entering a long period of unemployment at sea, Milne sought a career in politics, and he was selected to stand in the Tory interest as the M.P. for Berwick in February 1820. The campaign proved to be a controversial one, with Milne accused of instigating a delay of the poll to enable the late arrival of his London supporters on a steamer, and although he was duly voted in, his election was voided on 3 July. He nevertheless expended £5,000 over the next three years in seeking to become the M.P for Berwick, yet he was unable to secure selection. He was promoted vice-admiral on 27 May 1825, and whilst spending most of his time in Scotland, he was a frequent visitor to Suffolk Place in London and to the royal palaces. In April 1835 he faced a rowdy meeting of electors at Leith where he was bidding to sit in the Conservative interest, and after being taken to task over his opposition to the reform bill and his apparent support for the subjugation of the Irish Catholics, the assembly resolved that he was not a fit and proper person to sit for Parliament.

On 15 July 1839 Milne and his second wife took to the Jury Court of Edinburgh to claim damages against an author who had published a work including defamatory accusations over Lady Milne’s parentage and legitimacy. Documents and statements indicated that neither were in question and the Milnes were accordingly awarded damaged of one thousand guineas.

Milne was nominated a G.C.B. on 4 July 1840, and he was promoted admiral on 23 November 1841. On 27 April 1842 he raised his flag aboard the Caledonia 120 commanded by his son, Captain Alexander Milne, as the commander-in-chief at Plymouth, where he mostly resided ashore. Amongst other notables and royalty, he hosted Archduke Frederick of Austria in September 1842, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in September 1843, and the King of Saxony in July 1844. Although it was reported in March 1843 that he had been dangerously ill he soon recovered, and on 13 November he transferred to the Albion 90, Captain Nicholas Lockyer, before rejoining the Caledonia in February 1844 and attending a levee in London during the following month.

By the beginning of April 1845 he was once more in poor health, and shortly after relinquishing his command he died on the way home to Scotland on 5 May aboard the packet steamer Clarence, being buried in the Inveresk kirk yard.

Milne was married twice; firstly, on 16 April 1804, to Grace, the daughter of Sir Alexander Purves, who died at Bordeaux on 4 October 1814, and secondly on 8 September 1819 at Paxton House, near Berwick, to Agnes Stephen, the daughter of a planter from Grenada. She died on 27 January 1862. He had two surviving sons from his first marriage; the elder, David Milne-Home, born in January 1805, became a famed meteorologist and advocate, the younger, Sir Alexander Milne, born in November 1806, was flag-captain to his father aboard the Caledonia from 1842-5, sat on the board of Admiralty whilst still a captain, and eventually became the admiral of the fleet. Another son died in infancy. He bought Inveresk Gate in Inveresk in 1799, and during 1821 purchased the Berwickshire estate of Milne Graden. He also had a residence at 10 York Place in Edinburgh, and he saw some service as a local magistrate.

Milne was considered to be of a pleasant, gentlemanly disposition, and was a thorough-going seaman with an eye for detail. He was an expert in preserving the health of his men in dangerous tropical climates, although one historian, C. Northcote Parkinson, described him as ‘stupid’. Whilst serving off Cherbourg in 1813, he had his wife, two children and a maidservant aboard, much to the disgust of his fellow captains.