Sir Samuel Hood

1762-1814. He was born on 27 November 1762, the third son of Samuel Hood of Kingsland, Dorset, and of his wife Anne Bere of Westbury, Wiltshire. He was the younger brother of Captain Alexander Hood and a cousin of Admirals Viscount Hood and Viscount Bridport.

In 1776 Hood entered the navy aboard the Courageux 74, commanded by his father’s first cousin Samuel, and after moving into the Robust 74, commanded by his father’s other naval cousin, Alexander, he fought at the Battle of Ushant on 27 July 1778. For the succeeding two years he served in the Channel aboard the sloop Lively 20, Captain Robert Biggs, before sailing in December 1779 to the Leeward Islands with the promoted Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood aboard the Barfleur 90, Captain John Inglefield.

After being commissioned lieutenant on 11 October 1780 he was present at the Battles of Martinique on 29 April 1781, Chesapeake Bay on 5 September and St Kitts on 25/26 January 1782. He was promoted on 31 January to command the hospital ship Renard at Antigua, but continuing aboard the Barfleur as a volunteer, he fought at the Battle of the Saintes on 12 April and remained aboard her until he returned with the Renard to England at the peace in 1783.

efield.

For the next two years Hood lived in France, and on returning to active service in May 1785 he was ordered to commission the newly acquired sloop, Weasel 14, which he took out to Halifax in July. During May 1788 he was the junior member of the court-martial that erroneously passed a sentence of dismissal from his ship, rather than dismissal from the navy, on Captain Isaac Coffin of the Thisbe 28 for keeping false musters, although he became an immediate beneficiary of the verdict when on 24 May he was posted captain of that frigate. After returning to England in the autumn of 1789 the Thisbe was paid off in December.

Hood next commissioned the frigate Juno 32 in the spring of 1790, with which he sailed for Jamaica in June. On 3 February 1791 he saved the lives of three seamen from a wreck when he took to his barge in a hurricane to bring them off from their raft, for which act of bravery and humanity he was awarded a hundred guineas towards the purchase of a sword by the Jamaican House of Assembly. Returning to England in the summer of 1791 he spent a year stationed off Weymouth in attendance to the King, an ‘honour’ which saw him incur debts of £700 for the provision of entertainment to His Majesty and the royal hangers-on. When not hosting the King, he rarely ventured into port, preferring to battle the elements at sea and being engaged in anti-smuggling operations.

Five days after the formal commencement of hostilities with France on 2 February 1793 the Juno joined a squadron that was despatched under the orders of Commodore John Colpoys to protect the Channel Islands, and she returned to Portsmouth on the 18th having captured the enemy privateer Entreprenant. Undertaking further duty in the Channel, she made the further captures of the privateers Palme on 2 March, and Laborieux in April, the latter when she was in company with the Aimable 32, Captain Sir Harry Burrard.

In May 1793 the Juno sailed to the Mediterranean, and after a brief visit to Malta and being present at the occupation of Toulon Hood took her into the latter port on 11 January 1794 only to discover that it had recently been occupied by the French republicans following the withdrawal of Vice-Admiral Lord Hood and the royalists. The situation appeared even more hopeless when she went aground, but by using his audacious seamanship and quick wits he was able to extricate his frigate under fire and escape to the open sea. In early February, during the opening stages of the Corsican Campaign, the Juno served under Commodore Robert Linzee in the attack on the Martello Tower in the bay of that name in Corsica, and again Hood’s consummate professional skills prevented his command from suffering any serious damage.

After transferring to the Aigle 36 in the spring of 1794 Hood was given command of a frigate squadron in 1795 that was engaged in the protection of the Morean commerce, for which duty he was rewarded by the British merchants. In company with the Cyclops 28, Captain William Hotham, he blockaded two French frigates and a corvette in the port of Smyrna in December until being chased away by Commodore Honoré Ganteaume’s force of one sail of the line and five frigates.

In April 1796 he joined the Zealous 74 in the Mediterranean fleet, replacing the late Captain Lord Hervey who had been unable to maintain an acceptable discipline. Having gone aground near Tangiers the Zealous was unfortunately under refit in Lisbon at the time of the Battle of Cape St. Vincent on 14 February 1797, but from 21-25 July she was present in Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson’s unsuccessful assault on Santa Cruz, Tenerife, and Hood skilfully conducted negotiations on the instruction of Captain Thomas Troubridge which relieved the squadron from the consequences of its failure.

During 1798 the Zealous was initially employed in the Bay of Biscay and off Rochefort until she joined the elite force sent into the Mediterranean under the command of Rear-Admiral Nelson. Racing into action at the Battle of the Nile on 1 August, she was just beaten to the honour of leading the fleet by the Goliath 74, Captain Thomas Foley, but she put her first opponent, the Guerrierè 74, out of action within twelve minutes and whilst taking possession of that vessel immediately began engaging other opponents. The next day Hood attempted to chase those French ships which had been largely unscathed from the battle but was recalled. He later received the thanks of Parliament and a sword from the City of London for his services in the action, during which the Zealous lost one man killed and seven wounded.

After the majority of Nelson’s victorious fleet had left Egyptian waters, Hood initially remained behind to command the blockade of Commodore Ganteaume’s squadron consisting of two small sail of the line and eight frigates at Alexandria and Rosetta. He rejoined Nelson at Palermo in February 1799 and in the following month captured the French brig Courier 16. On 10 April he rescued a Neapolitan force from Salerno and hoisted the Royal Neapolitan standard there, and in respect of this service, and for also acting as the governor of the Castel Nuovo at Naples, he was rewarded by the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Following the breakout of the Brest fleet on 25 April 1799 the Zealous was ordered to join Nelson off Sicily, and she was subsequently with Rear-Admiral John Duckworth’s squadron at Minorca where she enjoyed some success in the capture of the enemy’s merchant shipping. She then returned home to be paid off at Chatham in early 1800, and Hood went ashore to settle his late brother’s affairs, Alexander having been killed when commanding the Mars 74 in the defeat of the Hercule 74 on 21 April 1798.

Hood next commissioned the brand new Courageux 74 in April 1800, serving in the Channel fleet and being attached to Rear-Admiral Sir John Warren’s expedition to Ferrol during August. The following January he joined the Venerable 74, again serving in the Channel fleet, and in March he sailed from Portsmouth with an East India convoy in company with the Superb 74, Captain Richard Keats, and Cambrian 40, Captain Hon. Arthur Legge. Remaining with these two vessels off the Iberian Peninsula, Hood’s ship captured two richly laden Spanish vessels, although a further lucrative convoy that had been expected did not materialise. The Superb and Venerable then joined Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez’ squadron which fought at the Battle of Algeciras between 6-12 July 1801 and Hood’s ship suffered badly in the final action, losing her fore and main masts, and then going aground and losing her remaining mast. He was ordered to abandon ship by Saumarez some dozen miles off Cadiz but instead managed to save his vessel and the Venerable was towed into Gibraltar, having sustained the substantial casualties of twenty-six men killed and one hundred and twelve wounded.

Once the Venerable was paid off at the peace in 1802 Hood briefly visited his father’s cousin Alexander, the ennobled Admiral Lord Bridport, before sailing out to Trinidad to serve as the joint commissioner, and he was therefore on hand when the terminally ill commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands, Rear-Admiral John Totty, left for home in June. Hood was appointed to act as commander-in-chief in Totty’s stead, raising his broad pennant initially on the Blenheim 74, Captain Henry Matson.

Upon the renewal of hostilities with France in 1803 island after island fell to Hood during a campaign that lasted from June to September, including St. Lucia on 21 June, Tobago ten days later, Demerara, and Essequibo and Berbice by September. Besides Martinique France was left with scarcely a foothold in the West Indies, and he even commissioned the Diamond Rock as a sloop of war on 7 January 1804, arming it with five heavy guns before capturing Surinam with Major-General Sir Charles Green on 5 May. During this period his broad pennant flew aboard the Centaur 74, Captain Bendall Littlehales, and later Acting-Captain Murray Maxwell, Captain Conway Shipley, and from 1804-5 Captain Charles Richardson. For his services he was nominated a K.B. in 1803, and as well as receiving countless awards from the local merchants for driving away the enemy privateers he was appointed a colonel of marines in 1805.

In March 1805, having been invested with the Order of the Bath at Antigua by the governor, Hood returned with the Centaur to Europe upon his replacement by Rear-Admiral Alexander Cochrane, and at the instigation of the new first lord of the Admiralty, Lord Barham. On 9 January 1806 he participated in the funeral of Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson, and then rejoining the Centaur he was attached to Vice-Admiral Sir John Warren’s force that was sent in pursuit of the French squadrons under Leissègues and Willaumez, a chase which eventually ended with the latter’s disbursement in the storm of 18 August.

In the meantime, Hood had been placed in command of the blockade of Rochefort with six sail of the line, and on 25 September 1806 his force intercepted a squadron of five French frigates and two brig-corvettes. Although four of the frigates were captured Hood was one of twenty-eight men wounded in addition to nine killed when he received a musket ball in the wrist. The wound necessitated the amputation of his arm, for which he was later awarded a pension of 500 guineas. During his subsequent convalescence he fought the Westminster election and was returned with Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the two of them being paraded with the Centaur’s seamen and effigies of Fox and Nelson from Covent Garden to St James’ Street. Resuming active duty on the Centaur with a commodore’s broad pennant, and with William Henry Webley acting as his flag-captain, he later cruised off the Canary Islands and Madeira.

During 1807 he served under Admiral Lord Gambier in the Copenhagen expedition which resulted in that city’s surrender on 7 September, and in line with seniority he was promoted rear-admiral on 2 October. With his flag still aboard the Centaur, Captain Webley, his squadron of four sail of the line and four frigates then brought a successful conclusion to the operations that had commenced with the evacuation of the Portuguese Royal family in November, by capturing Madeira on 26 December.

r.

In 1808, as second -in-command to Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez in the Baltic, Hood became involved in the Russo-Swedish War, and he was detached with the Implacable 74, Captain Thomas Byam Martin, to assist Britain’s ally, Sweden. The Centaur’s destruction of the Russian ship Sewolod 74 on 26 August under the noses of nine Russian sail of the line at a loss of one hundred and eighty men killed and wounded to his enemy and three killed and twenty-seven wounded to his own command was later deemed to be one of the greatest single-ship actions of the war; indeed the Swedish captain of the fleet was reported to have shed tears at its sheer brilliance, whilst Captain Martin, whose Implacable had originally forced the Sewolod to surrender before the Russian fleet rescued her, termed it ‘the most determined, well-arranged, glorious act that our naval history can boast of.’ Hood was duly rewarded by the King of Sweden with the Grand Cross of the Swedish Order of the Sword.

On 16 January 1809, with his flag aboard the Barfleur 98 commanded by his kinsman, Captain Samuel Hood Linzee, Hood was second-in-command of the navy in the Corunna Roads, and under his superintendence Major-General Sir John Moore’s army was safely re-embarked. The appreciation of his efforts was amply demonstrated by the House of Commons who applauded Hood to such acclaim when he rose to accept their thanks that he was unable to speak. In March he suffered a further wound when he was badly burned by a bedpan, but although he was unable to sit down for three weeks, he was no doubt somewhat mollified by being created a baronet on 13 April.

Upon resuming his service Hood returned to the Mediterranean where as second-in-command he led a division of the fleet with his flag aboard the Centaur, Captain Webley, briefly commanding the main body of the fleet at sea in early 1810 before a replacement for Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood arrived on that station, and shifting at the end of the year to the Hibernia 110 with Captain Webley. He returned home in July 1811 as a passenger aboard the Tigre 74, Captain Benjamin Hallowell, as he had been appointed commander-in-chief at Jamaica, but a few days after his arrival news was received of the death of Vice-Admiral William O’Brien Drury in the East Indies and he was instead appointed to command that station.

On 1 August 1811 he was promoted vice-admiral, and taking passage with his family and Captain Webley aboard the Owen Glendower 36, Captain Bryan Hodgson, he departed Portsmouth at the end of September, only to put back into Lymington within days because of bad weather. After seeking shelter at Falmouth a week later, he eventually departed home waters at the end of October. The voyage out to the East Indies was such a difficult one that concerns were expressed for the Owen Glendower’ survival, yet she eventually arrived at Madras in 1812 where Hood took the Illustrious 74 from Commodore William Broughton as his flagship, much to the annoyance of that officer. He moved with Captain Webley to the Minden 74 once she was brought out from Portsmouth by Captain Alexander Skene at the beginning of 1813, and after Webley returned home, she was later commanded by Captains Joseph Prior in 1813, and thereafter Captain George Henderson.

In January 1814 Hood flew his flag aboard the Theban 36, Captain Samuel Leslie, whilst sailing from Calcutta to Trincomale. By now he had expressed a wish to resign and return home overland to England, and indeed Rear-Admiral Sir George Burlton had been appointed to succeed him, but before the exchange could take place he died at Madras on 24 December 1814 after a three-day fever following a visit to Tippoo Sahib’s former palace at Seraingpatam. He was buried with a small ceremony, and when his widow arrived home in early June 1815 aboard the Malacca 36, Captain Henderson, with news of his death it was to find that Hood had been created a G.C.B. in January.

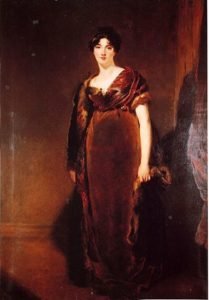

Admiral Hood’s wife, Mary Frederica Elizabeth MackenzieCC BY-SA 3.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php curid=7998416

On 6 November 1804 he married Hon. Mary Frederica Elizabeth Mackenzie, the eldest daughter and heiress of Lord Seaforth, the governor of Barbados, but as they had no issue his baronetcy passed to his nephew Alexander, the son of Captain Alexander Hood. His widow later married James Alexander Stewart, the politician and colonial administrator who was a son of Vice-Admiral Hon. Keith Stewart. Hood was the uncle of Captain Edward Woollcombe, and his address was given as 37 Lower Wimpole Street, London.

An acquaintance of Nelson and an extremely talented officer who was deeply attached to his trade, Hood was an expert in navigation, astronomy, geography, shipbuilding, and mechanics, was fluent in French and Spanish, and studied the customs and languages of every country he visited. Lord St. Vincent held him in the highest esteem, the more so that Hood shouted down Captain Lord Cochrane in the House of Commons during July 1807 when that fiery officer was attacking the earl.

Possessed of a strong constitution unlike his brother, he was a very tall, inelegant, and awkward man, as exemplified in one of his earliest commands, the Weasel, where he was obliged to stand with his head through the skylight so that his hair could be attended to. Tellingly, Lady Cavendish said of him ‘he has a foolish manner and does not look like a hero,’ for despite his rustic, gentle, cheerful, temperate, and naturally charming disposition, coupled with a pleasant voice and expression, he was greatly admired and in action was calm and precise. Even the French had a soft spot for him, as a result of Hood’s typical gallantry in returning the wounded from the Curieux to Martinique after the engagement in February 1804. He did not enjoy society and could be seen as reserved, for his whole being was dedicated to pursuing excellence in his trade.

He was the M.P. for Westminster from 1806-7 in the Grenville interest but was withdrawn from the seat in his absence by his friends and elected as the member for Honiton, which seat he held until 1812 in the interest of the retired secretary to the Admiralty, Sir Evan Nepean. His political persuasion was never clear, the Whigs being unsure of him, and he certainly supported the government against Lord Cochrane’s accusations of naval abuse.