Sir William Sidney Smith and the Brest Fleet’s Winter Cruise – January 1795

On Christmas Eve 1794, after several false starts, the Brest fleet of thirty-five sail of the line, thirteen frigates and sixteen smaller men of war under the command of Vice-Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret-Joyeuse, supported by Rear-Admirals François Joseph Bouvet, Pierre Jean Vanstabel and Joseph Marie Nielly, put to sea. Villaret-Joyeuse’s orders were to escort a squadron of six sail of the line, three frigates and a corvette under the command of Rear-Admiral Jean François Renaudin, south to the Bay of Biscay from where it could proceed to reinforce the Toulon fleet and thereby ease the demand for supplies at Brest. A similar sized squadron was also intended to be detached to Guadeloupe, allowing the remainder of the fleet to embark on a winter cruise against the British merchant shipping.

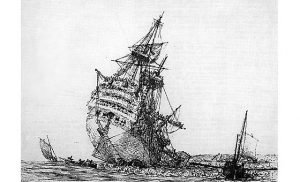

Many of the French officers regarded the decision to take to the winter seas as perilous in the extreme, as the ships were not only in poor repair with mutinous crews, but were also low on stores. Nevertheless, the despotic Committee of Public Safety gave the orders in France and to refuse them was not an option. Sure enough, the ships had not even worked out of the Goulet before the Républicain 110 went ashore on rocks in the centre of the passage, and despite jettisoning her guns she remained stuck fast. The next day her crew were taken off, although by then the incident had cost the lives of ten men. By 29 December the whole fleet had come to anchor off Camaret-sur-Mer, and it set sail again on New Year’s Eve, however the winter gales forced the Nestor 74 to turn back for Brest after she had lost a mast, and in the early days of January a fog saw several vessels under the command of Rear-Admiral Vanstabel separate from the main body of the fleet.

As early as 23 December reports had been reaching Plymouth that the Brest fleet was out, whilst intelligence received via the Netherlands claimed that thirty-five ships had been victualled for a month’s cruise and had probably embarked troops. An American ship that departed Lorient for Falmouth reported of advices being received at the former port to the effect that the Brest fleet was at sea with a supposed destination of the Mediterranean, and this information was relayed to the Admiralty on Christmas Day.

On 2 January three frigates under the command of Commodore Sir John Borlase Warren departed Falmouth to gather intelligence of the French movements, these vessels being his own pennant ship Flora 36, the Arethusa 38, Captain Sir Edward Pellew, and the Diamond 38, Captain Sir William Sidney Smith. The next day they were off Brest, and having taken on board a pilot, Smith disguised his frigate as a French man of war, and with his officers dressed in what passed for Republican attire he sailed inshore to reconnoitre.

At 2 p.m. the Diamond discovered three men-of-war working up towards her, one of which came to anchor an hour later about two thirds of the way between Ushant and Brest. At 5 o’clock, with the wind in the east, Smith anchored between Point St-Mathieu and the Pointe-du-Raz in order to gain the tide, his position being only two miles away from the enemy vessel, which would later be identified as the Nestor. Six hours later he got underway again and passed within half a mile of the anchored man-of-war. At 2 a.m. on the morning of the 4th, the Diamond passed the stranded Républicain in the Goulet, and then shortly afterwards a frigate anchored in the Basse Buzée. By now Smith’s command was at the entrance to Brest water and she proceeded on her course under easy sail across the harbour mouth, often within musket-shot of the enemy. Come daylight, fifteen smaller vessels were observed in the Camaret Roads, but having looked into Brest harbour nothing else was to be seen bar a vessel on the stocks and a sloop that was working out to sea.

Having completed his reconnaissance, Smith bore up for Point St-Mathieu at 7.40, and in response to a signal from the Chateâu de Bertheaume he ran up French colours. Shortly afterwards the sloop hove-to and made a signal, and when this went unanswered by the Diamond she hauled her wind and headed back into Brest. Anxious not to arouse any further suspicion, Smith eased his frigate alongside the Nestor, which with jury-top-masts aloft and with her main-deck guns apparently jettisoned, was pumping out her water. Explaining in his impeccable French that his frigate was part of a squadron that had been serving off Norway, Smith offered his assistance, and although this was declined, the Nestor’s captain did provide him with the valuable information that his ship had become detached from the fleet in the gale three days previously. Chivalrously declining to take advantage of the opportunity to rake the stranded enemy, and passing the crack frigate Virginie 40, Captain Jacques Bergeret, which displayed no interest in him, Smith sailed calmly out to sea and at 10.30 rejoined the Arethusa. Two days later the three British frigates arrived back at Falmouth from where Warren dispatched his first lieutenant, Thomas Eyles, to the Admiralty in London to confirm the reports that the French were at sea.

Once the newspapers received confirmation that the French were out an optimism that they would soon be brought to account by the Channel Fleet began to circulate. Yet this hope was soon revealed to be false, for at this stage of the war the British preferment was to winter her home fleet in port, and it would take the best part of two weeks for the ships to mobilise. Admiral Lord Howe was summoned from Bath where he had been residing for some weeks in poor health, and having returned to his flagship at Spithead he received orders from the Admiralty on 21 January to put to sea once reinforcements from Plymouth or elsewhere had brought the Channel Fleet up to number at least thirty-one sail of the line. In London the delay was the subject of much disquiet, and on 26 January Admiral Lord Hood, who was home on sick leave from the Mediterranean command, wrote to his brother and Howe’s second-in-command, Admiral Lord Bridport, expressing his apprehension that the Channel Fleet would still be off St. Helens after the French had returned to port. Such a calamity, he felt sure, would lead to ‘impeachment’. It therefore must have been of great disappointment to Hood and the more combative members of the establishment when Howe did eventually get away from Portsmouth on the 29th, for having been further delayed by adverse winds he merely made for Torbay with the intention of offering protection to the outgoing East and West India convoys.

The cautious British response may have allowed Villaret-Joyeuse’s ships to avoid a battle, but they were unable to elude the winter weather. On 28 January Rear-Admiral Vanstabel and his division of eight ships was forced to return to Brest due to the on-going fog, but they were the fortunate ones, for once a gale hit the remainder of the fleet it was dispersed in tatters. The Neuf Thermidor 80, Scipion 80 and Superbe 74 were all abandoned and left to founder with a great loss of life on the former vessel which had fought as the Jacobin at the Battle of the Glorious First of June, the Neptune 74 was beached at Péros near Morlaix with the loss of fifty men and could not be re-floated, the Téméraire 74 sought shelter in St. Malo, the Fougueux 74 made it into a harbour on the Isle of Groix, and the Convention 74 crawled into Lorient. The remaining vessels eventually returned to Brest during the first two days of February. On the credit side, his cruise did net Villaret-Joyeuse some hundred British merchantmen in captures, in addition to the Daphne 20, Captain William Cracraft, who as her senior lieutenant had so boldly fought the Brunswick 74 at the Battle of the Glorious First of June following the fatal wounding of Captain John Harvey.

Meanwhile Lord Howe’s fleet of forty-two sail of the line, including a squadron of five Portuguese ships, had been detained by the gales in Torbay, during which storms nine sail of the line had parted from their moorings. When he did eventually get to sea on 14 February he escorted the East and West India convoys to a safe latitude, and then learning that the French were back in Brest he returned to Spithead where on the 28th he turned the command over to Bridport and went ashore again for the benefit of his health. Taking advantage of the British open blockade, the French quickly refitted Rear-Admiral Renaudin’s ships, and on 22 February the Jemmappes 74, Jupiter 74, Mont Blanc 74, Révolution 74, Tyrannicide 74, and Aquilon 74 sailed from Brest with three frigates and some smaller vessels to eventually reach Toulon on 4 April.

I think the Guadeloupe part of the fleet has arrived on January 5 or 6 in Pointe-à-Pitre. A register of Bataillon des Antilles which are a part of this squadron – they should have come to Brest to be equipped here. They have arrived in the beging of January 5 or 6, 1795 on Guadeloupe, cf. LACOUR 1857: 400-401, and Reading Mercury 23.02.1795, and SHD Vincennes Bataillon des Antilles as a part of it GR 43 YC 31 (17/11/1794), 200 black soldiers with Magloire Pélage and Louis Delgrès, who play a role in May 1802. To arrive in January , they must have sailed off in Brest in November. Until now, I did not find any “intelligence” in English newspaper or Brest newspaper.

Hi Sandra – thanks for getting in touch. I’m sure that you are correct – Admiral Caldwell stated that two or three frigates arrived at Guadeloupe on 6 January 1795 with a convoy, so it begs the question as to whether Villaret-Joyeuse had orders to detach further reinforcements to Guadeloupe when he left Brest on 24 December 1794, or whether the information that he had to detach such a force is simply erroneous. I’ll try and do some more investigating…..