Sir John Talbot (1768-1851)

An Irish aristocrat, and a talented and respected captain, Talbot’s long and varied career saw devoted loyalty from his men on one ship when mutiny raged through the fleet, but conversely a mutiny on his next command. His employment culminated in the successful (if bloody) capture of a French ship of equal force and a knighthood.

The Talbots were an ancient and prominent aristocratic family based in Malahide, just north of Dublin. John was the fourth son (and tenth of fourteen children) of Richard Talbot of Castle Malahide and Margaret O’Reilly, who became the Baroness Talbot of Malahide in 1831. His brothers included Richard, 2nd Baron Talbot of Malahide and Hon. Thomas Talbot, who emigrated to Canada where he became an important land-owner and politician. One of his sisters married Sir William Young M.P. and another married Lieutenant-General Sir George Airey. He was also related by marriage to Admiral Sir Charles Ogle and to Admiral Hon. Duncombe Pleydell Bouverie.

Young John was educated at Manchester Grammar School, which explains why he was the comparatively advanced age of fifteen when he entered the Navy in March 1784. His first ship was the frigate Boreas 28, Captain Horatio Nelson, going out to the Leeward Islands for peacetime duty. Talbot was one of several dozen prospective officers aboard the ship during its three years in the West Indies. Initially he was rated as captain’s servant, progressing to midshipman and then master’s mate under Nelson’s tutelage. The Boreas returned to Britain in the summer of 1787 and was paid off in December. In May 1788 Talbot joined the Portsmouth-based guardship Barfleur 98, occasionally flying the flags of Vice-Admiral Lord Hood and later Vice-Admiral Robert Roddam, and during the Spanish Armament in the summer of 1790 he saw service aboard the Victory 100, Captain John Knight, which once again flew Hood’s flag. On 3 November 1790, aged 21, he was amongst scores of officers commissioned lieutenant at the conclusion of the Spanish Armament. The following year the newly- promoted Talbot was appointed to the Triton 28, Captain George Murray, surveying the Belt (the Danish passage to the Baltic), before going out to Quebec, Halifax, and Jamaica.

In April 1793, following the outbreak of the French Revolutionary War, Talbot joined the Windsor Castle 98, Captain Sir Thomas Byard, the flagship of Vice-Admiral Phillips Cosby, seeing service in the Mediterranean and at the occupation of Toulon in the autumn. Moving with Byard in August 1794 to the Alcide 74 on the same station, he left that ship in December after she had come home to Portsmouth and been paid off. In early 1795 he was appointed the first lieutenant of the Astrea 32, Captain Lord Henry Paulet, serving in Rear-Admiral John Colpoys’ squadron in the Channel. On 10 April she captured the French frigate Gloire 36 after an hour’s engagement, a most impressive feat in view of the enemy’s considerably greater firepower. After taking the prize into Portsmouth, Talbot was rewarded for his part in the engagement by being promoted commander on 17 April.

Taking command of the sloop Helena 14, Talbot saw service for much of 1795 in the Channel with Commodore Sir John Warren’s squadron, and on 16 March 1796 he distinguished himself when he led four cutters into the port of Ostend under fire from the batteries to cut out a ship carrying a valuable cargo of claret.

Posted captain on 27 August 1796 at the age of 28, he was appointed to the small frigate Eurydice 24, which was undergoing a thorough repair at Sheerness. One of his first duties was to take a convoy of troopships around to Spithead from the Nore. On 15 December he captured the Dunkirk privateer Sphinx, after that vessel had approached the Eurydice in the mistaken belief that she was a merchant vessel. His ship continued to cruise off the Downs: in February 1797 she took the Dunkirk lugger privateer Flibustier after a three-and-a-half-hour chase, and in March seized the tiny privateer Voltigeur off the Flemish banks.

Though her ship’s company had petitioned the Admiralty to remove her ‘tyrannical’ first lieutenant the year before, when the Spithead mutiny broke out on 16 April, Eurydice (a ‘happy ship’) remained loyal. In fact, the crew wrote to their captain to express their feelings of ‘love and esteem’, describing him as ‘a Gentleman so Worthy and Deserving of the Confidence of our Family of which you are the Father’.

At the end of May 1797 after the end of the Spithead mutiny, the Eurydice sailed for Quebec with a convoy in company with the frigate Thames 32, Captain William Lukin. She returned with an eastbound bound convoy reaching Lisbon in early November. After the Eurydice had arrived in English waters in January 1798 with the Lisbon convoy, Talbot earned praise for not having lost a single ship from his flock. His ship participated in the defence of the island of St. Marcou (occupied by British troops as a base for light vessels) off Cape La Hogue when it came under attack by French forces during April. In early May the Eurydice entered Portsmouth for a refit, and for the majority of August and September she was off the Isles de Brehat on the north coast of Brittany, where Talbot led a small squadron which blockaded a French convoy of 23 vessels laden with naval stores that had been bound to Brest under the escort of three small men-of-war. Continuing in the Channel, the Eurydice chased a privateer lugger away from Jersey in the last week of October, allowing the vessel to be driven ashore on Cape La Hogue by the Arethusa 38, Captain Thomas Woolley.

The Eurydice’s movements over the next few months are unclear, although in November 1798 a correspondent from Great Yarmouth reported that she had gone aground on the Happisburgh Sands off the Norfolk Coast with the waves breaking over her, and that she had cut away two of her masts. At the time the wind was hurtling in from the northeast and it would not have been possible for the North Sea Fleet to provide her with any assistance. It is certain however that by the first week of January 1799, she was in service, and that month she sailed from Portsmouth with a small squadron to blockade Le Havre.

In April 1799 the Eurydice was again detailed to escort the Quebec convoy, sailing in company with the Topaze 32, Captain Stephen Church, and returning with the homeward bound convoy in mid-September. During the latter passage she detained a Danish West Indiaman as a prize in the entrance to the Channel, but this vessel was unfortunately wrecked when coming through the Needles off the Isle of Wight. In early November, Talbot’s frigate escorted a convoy from Portsmouth around to the Downs, and in company with the sloop Snake 18, Commander John Mason Lewis, she captured the Calais privateer Hirondelle 14 near Beachey Head a few days later.

Despite reports that he was to move in January 1800 to command a larger frigate (the Ambuscade), Talbot continued in the smaller Eurydice in home waters throughout the year. The ship cruised out of Plymouth and Falmouth in the spring, sailed for Ireland in June and then entered Sheerness in the following month, presumably to be refitted. She departed St. Helens on 6 August with troop transports as part of a secret expedition to assist French Royalist uprisings on the Atlantic coast, and then operated out of Plymouth.

On 1 January 1801 Talbot was appointed to the frigate Glenmore 36, serving on the Irish station. In June he retook four West Indiamen, part of the homecoming Leeward Islands convoy, which had been captured by the fast-sailing French privateer Braave 36. Despite the prospect of prize money resulting from these successes, some of the Glenmore’s crew were dissatisfied enough with their circumstances to mutiny, refusing to obey orders. Surprisingly in view of the attitude of the Eurydice’s crew, Talbot was accused of treating the Glenmores more harshly than her previous, popular captain (‘a paternal officer’) George Duff. Five ringleaders who were accused of taking an oath ‘not to proceed to sea while the ship was commanded by Captain Talbot’ were brought to court-martial at Portsmouth at the end of September. Three of the men were acquitted but two were sentenced to hang, an indication of the Royal Navy’s severe reaction to any hint of mutiny in the aftermath of the events of 1797. While there is no doubt that Talbot had ordered more floggings than his predecessor, he may have felt that discipline under Duff had been too lax.

Thereafter the Glenmore resumed her routine convoy duty on the Irish station, with few occurrences of note. Following the end of the French Revolutionary War in the spring of 1802 she arrived at Plymouth on 9 June, but despite reports that the frigate would be broken up as she was ‘old and crazy’, she remained in commission, though serving as a troopship. Talbot handed over command to Captain John Maitland in July.

He was not immediately re-employed when hostilities with France reopened in May 1803, probably because he was out of the country at the time. In early September he arrived at Falmouth from the Leeward Islands aboard the packet Prince Ernest, suggesting that he might well have been visiting a plantation on the island of Montserrat that he was to inherit some years later.

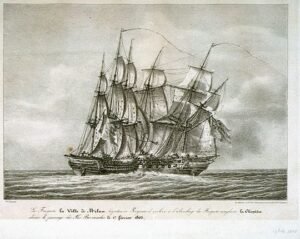

The action between the Ville de Milan and the Cleopatra. Talbot’s Leander took both ships with one warning shot.

On 20 October 1804 (when the Napoleonic War had been raging for almost eighteen months), Talbot returned to employment. He was appointed to command the Leander 50 on the North American Station, taking passage to Halifax in early November aboard the Cleopatra 32 Captain Sir Robert Laurie. In a surprising twist, three months later on 23 February 1805, Talbot and the Leander recaptured the Cleopatra, which had been taken a week earlier by the French frigate Ville de Milan 40. The French warship also submitted to the Leander – both enemy vessels had been extensively damaged in the earlier action, and unable to defend themselves, surrendered to Talbot after a single warning shot.

The Leander continued on the American station through to the end of 1805 when Talbot exchanged with Captain Henry Whitby into the Centaur 74. The Centaur had received orders to sail home, and Whitby, who had recently married the daughter of Captain John Inglefield, the naval commissioner at Halifax, unsurprisingly wished to remain on that station. Upon leaving the Leander, her officers presented Talbot with a beautiful hundred-guinea sword by way of a parting gift. The Centaur’s arrival at Plymouth on 15 January 1806 was greeted by a massive thunderstorm which shivered her three topmasts rendering them useless; as a result she was taken into the dock for repairs.

Within weeks of his return home, Talbot was appointed to another vessel on a distant station – the Thunderer 74. He travelled out to the Mediterranean to supersede Lieutenant John Stockham, who had temporarily commanded her at the Battle of Trafalgar. (Her captain, William Lechmere, had been recalled to England as a witness at Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Calder’s court-martial.) Initially sent up the Mediterranean from Gibraltar to join Rear-Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith’s squadron on the Neapolitan coast, in September the Thunderer returned to Gibraltar before sailing to join Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood with the bulk of the fleet off Cadiz.

On 1 November 1806 the Thunderer departed the fleet off Cadiz to join Vice-Admiral Sir John Duckworth’s mission to the Dardanelles. The objective was to dissuade Turkey from allying with France by sending a squadron through the narrow Dardanelles Strait to overawe the Turks at their capital, Constantinople. The intended show of strength proved a failure, as the squadron reached the Turkish capital, but then retreated back through the Narrows, receiving significant damage on the way out. The Thunderer distinguished herself in Rear-Admiral Smith’s attack on the Turkish squadron off Point Pesquies (Nara Burnu) during the passage up to Constantinople, though she suffered casualties of two men killed and fourteen wounded on the return journey. By May she was back at Gibraltar before heading up the Mediterranean, and in the autumn and winter of 1807 she was stationed off Palermo under the orders of Vice-Admiral Edward Thornbrough for the protection of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. She continued under this officer in 1808 during operations which followed the breakout of the Brest squadron on 7 February.

On 9 August 1808 the Thunderer arrived at Gibraltar from Palermo with a Neapolitan royal party and the Duke of Orleans, a senior member of the deposed French royal family. He remained aboard for the journey to Portsmouth at the end of the month. Though the ship was originally to be paid off, reports of a Russian threat to the allied Swedish fleet in the Baltic, resulted in orders for the Thunderer (along with other ships of the line at Portsmouth) to reinforce the North Sea Fleet after it had sent ships into the Baltic. Reaching Yarmouth on 19 September, a fortnight later Talbot assumed the command of the squadron blockading the Texel, a naval base on the Dutch coast. This proved to be but a brief assignment, for on 5 November the Thunderer arrived at Sheerness prior to proceeding to Chatham to be paid off three weeks later. While on leave in London, Talbot attended Queen Charlotte’s levee in January 1809.

Following almost a year on the beach, our man was appointed to the Victorious 74 in October 1809, sailing for the Mediterranean at the end of the following month to join Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood at the blockade of Toulon. During the autumn of 1810 his command was employed in the defence of Sicily against the forces of Marshal Joachim Murat (the King of the Naples), patrolling the Straits of Messina under the orders of Rear-Admiral Sir George Martin. A few months later Talbot was assigned to blockade Corfu (occupied by the French), commanding a squadron including the Leonidas 32, Captain Anselm Griffith, and Imogene 16, Captain William Stephens. On 30 January 1811 his squadron succeeded in driving the Italian schooner Leoben 10 ashore on the coast of Albania, whereupon her crew destroyed her. The Victorious continued to serve in this theatre of operations; at the end of the year she carried the Austrian Archduke Francis to Cagliari, Sardinia, where he was to marry Princess Mary Beatrice of Savoy.

In the early part of 1812, the Victorious was stationed off Venice in company with the Weazel 18, Commander John William Andrew, keeping watch on the French ship of the line Rivoli 74, which was commissioning in the port. On 21 February the Rivoli put to sea, accompanied by three brigs and two gunboats. After a twelve-hour chase, in the darkness of the early morning of the 22nd, the Weasel caught up with the French brigs and soon destroyed one. A few minutes later the Victorious brought the Rivoli under fire, and the two ships hammered one another broadside to broadside in an engagement that lasted five hours. Finally, the French ship surrendered, having lost four hundred men killed and wounded out of a crew of eight hundred and ten. Early in the engagement Talbot received a severe splinter wound to the head, but his first lieutenant, Thomas Ladd Peake, stepped in to command the ship during the rest of the fight. The casualties on the British ship were severe: twenty-seven killed and ninety-nine wounded (including the captain). Single-ship actions between ships-of-the-line were far rarer than those between frigates, and Talbot’s unusual success was rewarded with the highly coveted Naval Gold Medal from the Board of Admiralty, while his first lieutenant, Thomas Ladd Peake, was very appropriately promoted to commander.

At the beginning of July 1812, the Victorious arrived at Plymouth with her (much admired) prize, and she began refitting at Chatham. This process was protracted, and only in November did she arrive at Portsmouth to be fitted out for foreign service. Sailing for the West Indies with a convoy from Spithead in November, she was subsequently employed in Rear-Admiral George Cockburn’s campaign in the Chesapeake in March-August 1813. Returning north, on 12 November, she survived a hurricane at Halifax that damaged about ninety other vessels, driving a number on shore.

In the early part of 1814, the Victorious blockaded the U.S. frigates United States 44, Macedonian 38 and the sloop Hornet 20 in New London, Connecticut. During this duty she ran aground on Fisher’s Island and was only re-floated with great difficulty thirty-seven hours later. Talbot and his ship were then ordered on a most unusual mission, to protect the whaling fleet in the Davis Strait, which was believed to be the target of American cruisers. Victorious was by far the biggest ship ever to penetrate this far north (she reached 67° N), and the whalers she met were surprised at her presence in light of the inaccuracy of the charts of the area. Talbot seems to have ignored (or perhaps felt his orders precluded) the advice of these experienced mariners and continued sailing in conditions of poor visibility. On 8 July, the Victorious hit a rock near Disko Island high up in the Labrador Sea on the western coast of Greenland. The collision holed her and knocked off the false keel, but by fothering (wrapping) a sail over the hole the crew reduced the leak. As the ship limped back to England, escorted by her consort, the Horatio 38, Captain William Henry Dillon, the crew had to man the pumps continuously to expel water from the leak. Upon arriving at Spithead on 10 August in what was described as ‘a perilous state’ she was immediately paid off.

Though the American War was not yet over and the Hundred Days was still to come, Captain Talbot did not see any further service. He had been created a colonel of marines (a rewarding sinecure warded to a few senior captains) in June 1814, but a more important honour came six months later when he was nominated a K.C.B. (Knight Commander of the Bath) on 2 January 1815. Most of the RN officers receiving this honour were admirals; only 19 post-captains were included in the lists of knights. In line with seniority, he became a rear-admiral on 12 August 1819, in recognition of which promotion he attended a royal levee during the following year.

On 17 October 1815, at the advanced age of 47, he married the Hon. Juliana Arundell, the third daughter of the ninth Earl Arundell of Wardour, from a long-established Catholic family. They had eight children, of whom one died in infancy, but the others for the most part lived long lives. Juliana died on 9 December 1843, by which time the children were either grown adults or away in school. Apparently, Talbot converted to Catholicism late in life (his mother had remained a Catholic when his father converted to Protestantism), although when he married and his children were baptised the ceremonies took place in the Anglican church.

In 1812 Talbot inherited the Delvin Plantation with its 112 slaves in Montserrat from his maternal great-uncle, John Nugent of Westmeath, the lieutenant-governor of Tortola. He spent time in the Leeward Islands during 1821 (presumably to inspect his inheritance), returning home in the packet Manchester during August of that year. The plantation still retained 102 slaves in 1831; following the abolition of slavery he received compensation of about £1600 in 1836 from the Government for the loss of his ‘property’.

After the end of the wars, Talbot enjoyed a socially active retirement in Dorset, living at his home (Rhode House) just outside of Lyme Regis, and managing his 1,500 acre estate. The Talbot family prosperity is indicated by the fact that in the 1841 census the admiral and two of his children are shown as attended by nine servants and an agricultural labourer. He was promoted vice-admiral on 22 July 1830, attending a levee for the new King, William IV to commemorate the step shortly afterwards. He became a full admiral on 23 November 1841, which saw him attend the inevitable royal levee (this time with Queen Victoria) in March 1842. Despite strong suggestions that he might be appointed commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, or given the same role at Plymouth, he remained on the beach. However, he was further honoured by being awarded the G.C.B. (Knight Grand Cross of the Bath) on 23 November 1842, and he was one of 67 surviving shipmates who in 1847 claimed the Naval General Service Medal for the capture of the Rivoli.

Admiral Sir John Talbot died at his residence, Rhode House, Lyme Regis on 7 July 1851 in his 82nd year. He was a genial man, and much admired by his men, as illustrated by the crew of the Eurydice referring to him as their ‘tender shepherd’.