Sir George Cockburn

1772-1853. Born on 22 April 1772 in London of Scottish descent, he was the second son of Sir James Cockburn, Bt. of Langton, Berwickshire, the Tory M.P. for Peebles who later suffered financial ruin, and of Augusta Ayscough, a daughter of the Dean of Bristol. He was the younger brother of Major-General Sir James Cockburn, the governor of Curaçoa following its capture on 1 January 1807, and later of Bermuda. He was also the elder brother of the Rev. William Cockburn, the Dean of York, who married the sister of Prime Minister Robert Peel, and of Alexander Cockburn, a diplomat. A cousin was Admiral John Ayscough.

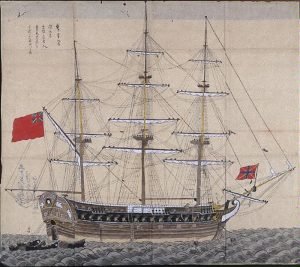

Whilst being educated under various tutors at Marylebone, Margate, and Roy’s Navigational School in Old Burlington Street, London, Cockburn was entered as a captain’s servant to the books of the frigate Resource 28, Captain Bartholomew Samuel Rowley, in 1781, and then of the yacht William and Mary. He first went to sea in 1786, joining the sloop Termagant 22, Captain Rowley Bulteel, which was employed in the preventative service in the North Sea. He afterwards saw service in the East Indies under the guidance of Captain Robert Moorsom of the Ariel 14, which sailed with the Cornwallis Expedition in February 1789, and after returning to England with Moorsom aboard the East Indiaman Princess Royal in May 1791 he joined the frigate Hebe 38, Captain Alexander Hood, serving in the Channel. At the time that this vessel was paid off in March 1792, he was holding the rating of master’s mate.

On 14 June 1792 he was placed aboard the Romney 50, Captain William Domett, the flagship of Rear-Admiral Samuel Granston Goodall in the Mediterranean, and remaining on that station, he was shortly afterwards appointed the acting-lieutenant of the frigate Pearl 32, Captain George Courtney, which returned to Spithead in August 1792.

On 27 January 1793, with the French Revolutionary War about to commence, Cockburn was given a commission as the second lieutenant of the Orestes 18, Commander Lord Augustus Fitzroy, which at the time was stationed in the Downs. After returning to England with that vessel from the Mediterranean in April, he was appointed on the 28th to the position of ninth lieutenant on Vice-Admiral William Hotham’s flagship Britannia 100, Captain John Holloway, sailing back to the Mediterranean on 11 May. Here he joined Admiral Lord Hood’s flagship Victory 100, Captain John Knight, as her tenth lieutenant on 2 July.

With the occupation of Toulon from August to December presenting many opportunities for advancement, he had already risen to become the Victory’s first lieutenant when he was promoted commander of the sloop Speedy 14 on 12 October. With this vessel, he exhibited great skill and tenacity during the particularly severe winter gales off Genoa, remaining on his station whilst all the other ships of the squadron were forced to retire into port. As a consequence, he was rewarded with the acting captaincy of the frigate Inconstant 36 for Captain Augustus Montgomery on 20 January 1794, although this was a position he was only required to fill for a month.

On 20 February 1794 Cockburn was posted to the twelve-pounder Meleager 32, which served off Corsica and Toulon during the rest of the year and acted as the repeating frigate at both the Battle of Genoa on 13/14 March 1795 and the Battle of the Hyères Islands on 13 July. He was thereafter employed in the Gulf of Genoa under the orders of Commodore Horatio Nelson in support of the Austrian army, being present when the squadron took eleven French prizes out of a munitions convoy in the Bay of Alassio on 26 August, and earning praise for an attack on shipping under the batteries of Larma on 31 May 1796, which netted him six prizes. All was not well within the squadron however, for Captain Charles Sawyer had been engaging in homosexual activities with members of the crew of the frigate Blanche 32, resulting in her first lieutenant, Archibald Cowan, alerting Cockburn who referred the matter to Nelson. The matter was largely hushed-up and Sawyer was removed from the command of the Blanche in June. Meanwhile, on 30 June the Meleager arrived with Nelson at Leghorn after that port had recently fallen to the French, and Cockburn was ordered to assist in the protection of a rapidly assembled out-going convoy.

In August 1796 he joined the eighteen-pounder frigate Minerve 38, which had been taken from the French the year before, and in which he was initially employed blockading Leghorn. In December he received Commodore Horatio Nelson’s broad pennant, and as might be expected, glory followed almost instantaneously with his defeat on 20 December off Cartagena of the Spanish frigate Santa Sabina 40, commanded by Captain Don Jacobo Stuart, although unfortunately the prize had to be abandoned when further Spanish ships appeared on the scene. A French privateer, the Monica 6, was captured three days later when the Minerve was in passage to evacuate the British personnel from Elba, and after the governor, Sir Gilbert Elliot, had been embarked at Porto Ferrajo, the Minerve had to escape from another two Spanish ships of the line off Cape Spartel on 11 February 1797. That night she sailed through the Spanish fleet in her rush to warn Admiral Sir John Jervis of the enemy’s approach, and the Minerve was thus present at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent on 14 February. Following the engagement, she formed part of a detached squadron that was sent to tackle the damaged Santisima Trinidad 130, but Cockburn’s senior officer, Captain Velterus Berkeley, controversially called off the chase when the Minerve was close enough to rake the giant Spanish vessel.

Further service followed off Cadiz and the Canary Islands, where in company with Captain Benjamin Hallowell of the Lively 32, Cockburn discovered a treasure galleon at Tenerife which led to Rear-Admiral Nelson’s disastrous attack on Santa Cruz in July 1797. Meanwhile, on 29 May the Minerve’s boats and those of the Lively commanded by Lieutenant Thomas Masterman Hardy cut the brig Mutine 14 out from Santa Cruz. On 1 September the Minerve captured the French letter-of-marque Marseillais 24 under the batteries on Gran Canaria, from where she departed with this valuable prize for Gibraltar. Whilst refitting at the Rock on 5 November, Cockburn led a small party of gunboats in the defence of a becalmed merchant convoy that had been attacked by Spanish gunboats coming out from Algeciras, and after briefly returning to the Canary Islands, he rejoined the commander-in-chief, Admiral the Earl of St. Vincent, at Lisbon in February 1798.

In March 1798 the Minerve was sent to England with a convoy, from which she was detached in early April with the trade for Bristol, Liverpool, and Chester. Dropping down to Portsmouth, she underwent a refit which lasted until November, and so after being presented to the King by Admiral Lord Hood at a levee on 16 May, Cockburn was able to spend time ashore with his family.

On 27 December 1798, the Minerve returned to duty in the Mediterranean with Cockburn at the helm. She participated at the siege of Malta and was engaged off the Riviera in operations against the coastal traffic and batteries until May 1799, when she joined Rear-Admiral Lord Nelson’s squadron off Sicily during operations to counter the threat of the Brest Fleet, which had broken out on 25 April. On 2 June she was off the south-east of Sardinia in company with the Emerald 36, Captain Thomas Waller, when they captured the French privateer Caroline 16. Being detached to reconnoitre Toulon, the Minerve joined Vice-Admiral Lord Keith’s fleet and was present at the capture of Rear-Admiral Jean-Baptiste-Emmanuel Perrée’s frigate squadron on 19 June. Once the threat of the Brest fleet had rescinded, she returned to the waters off Genoa in support of the Austrian army.

Throughout 1800 the Minerve appears to have been serving off Portugal, where in reporting to Vice-Admiral Lord Keith, the new commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean fleet, Cockburn had other ships under his command. A series of captures followed, including the Nantes privateer brig Furet 14 on 2 March, the French privateer Vengeance 15 on 15 May when in company with the hired vessel Netley, Lieutenant Francis Bond, and the Bordeaux privateer Mouche 20 in the early autumn.

At the end of January 1801, the Minerve limped into the Tagus having endured a singularly unsuccessful cruise and foul weather which had seen her men reduced to a single pint of water a day. She sailed to join Lord Keith off Cadiz on 10 February with intelligence that Rear-Admiral Honoré Ganteaume’s fleet was at sea after its breakout from Brest on 7 January, and she captured one of Ganteaume’s support ships in March after it had sailed out from Toulon. Remaining in the Mediterranean, Cockburn magnificently enhanced his reputation with the re-capture of the Success 32 and the destruction of the French frigate Bravoure 40 off Leghorn on 2 September.

Giving passage to the sickly and grief-stricken Rear-Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, who had recently learned of the death of his son in Egypt, the Minerve returned to Portsmouth on 1 December 1801 from Gibraltar in fourteen days, and whilst at the Hampshire port in early January 1802 a Hermione mutineer was arrested after being recognised in one of the frigate’s boats. The Minerve then sailed from Portsmouth to Deptford on 5 February to be paid off, and with peace being declared with France, Cockburn remained on the beach for the next seventeen months.

On 12 July 1803 he was appointed to the 18-pounder frigate Phaeton 38, initially serving off Le Havre before he was ordered to undertake the duties of second in command in the East Indies. Prior to taking up this post, he was required to deliver the new British ambassador to the United States, Anthony Merry, together with his wife, to North America, from where he was to convey specie to Madras, this money being compensation for loyalist losses in the American War of Independence. Setting sail from Portsmouth on 26 September, the Phaeton landed the ambassador at Norfolk and on 10 November anchored at New York to undertake quarantine. Here, some of the crew deserted the ship by the simple ruse of getting one man to jump overboard and then manning a boat to rescue him. During this incident the gunner, who had also taken to the boat, was knocked down and gagged, and when the boat reached Long Island he was cast adrift. Cockburn characteristically demanded permission from the local authorities to seek out his men on American soil, in which task he was successful.

Having left the Chesapeake on 28 January 1804, the Phaeton reached Madras on 26 May before sailing up to Bengal, where she arrived on 2 June. Initially despatched with two sail of the line and a 44-gun vessel to seek out Rear-Admiral Charles Alexandre Durand Linois’ raiding squadron in Batavian waters, by early August the Phaeton was at Bencoolen, the modern-day Bengkulu on the south-west coast of Sumatra. After returning to Madras, she was dispatched to blockade the Isle de France, where she took several prizes as well as engaging the land batteries. On one occasion she responded to the fire of heated shot from a fort on Point Cannoniére, and in so doing struck the furnace itself, sending the heated shot fizzing around the fort and setting it alight. Whilst this bombardment was in process, her boats captured and burned the vessel which she had earlier chased ashore under the battery.

Towards the end of January 1805, the Phaeton arrived at Bombay with the Tremendous 74, Captain John Osborne, and the Lancaster 64, Captain William Fothergill, having recently captured a Dutch East Indiaman from Batavia. After returning to the Bay of Bengal, Cockburn transferred to the recently purchased frigate Howe 38 on 5 June in order to give passage home to the governor-general of India, the Marquess Wellesley. Departing the Hoogley on 25 August, the Howe reached St. Helena on 14 November and anchored in home waters on 7 January 1806. She then departed Portsmouth for the Downs with a convoy two weeks later to be paid off in February.

After a period of recuperation ashore, Cockburn assumed the command of the Captain 74 in July 1806, although her initial voyage out to St. Helens on the 13th caused some astonishment amongst the assembled shipping when she ran onto a shoal known as the ‘Buoy of the Horse’, necessitating a good deal of effort to remove her. For some weeks she remained at St. Helens with the Ganges 74, Captain Peter Halkett, awaiting troops from Margate to transport out to the Mediterranean. What was termed ‘The Secret Expedition’ consisting of forty sail eventually departed on 19 August for Plymouth, off which port it appeared four days later. With the winds proving contrary, the expedition remained in Plymouth Sound, and whilst awaiting clearance to sail the Captain and Ganges were ordered to put out on 29 August with a squadron under the orders of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Louis to participate in the search for Rear-Admiral Willaumez’s squadron, which unbeknownst to the British had already been dispersed in a hurricane on 18 August. The squadron did have some success with the capture of the French frigate Presidente 44 on 27 September, and on 14 October the Captain and Ganges arrived back at Plymouth from Belleisle.

Rejoining ‘The Secret Expedition’, which was in fact a troop force bound for the Cape under the orders of Brigadier-General Robert Crauford, the Captain and Ganges arrived at Falmouth from Plymouth on 24 October 1806, from where the mission eventually left on 12 November to arrive at Porto Praya in the Cape Verde Islands on 14 December. No longer required as an escort, the Captain and Ganges departed the islands on 11 January 1807 to reach Portsmouth on 11 February. Fifteen days later, the two vessels left St. Helens with a convoy of twenty-two ships including a dozen East Indiamen, and having seen them to a safe latitude they joined Commodore Sir Samuel Hood’s squadron, which was cruising between the Cape Verde Islands and Madeira. After returning to Falmouth with Hood on 11 June, the Captain and Ganges sailed two days later for Plymouth where Cockburn left his ship at the end of the month.

For the next nine months he ran with the social set ashore, joining many luminaries including the Prince of Wales at Cheltenham in August 1807, and visiting Bath in early 1808. On 10 March he was appointed to the newly commissioned Aboukir 74 which had recently been launched at Chatham, but as her fitting out had not been completed he instead joined the Pompée 74 two weeks later. His new command arrived at Portsmouth from Chatham via the Downs on 16 May, and she then proceeded around to Plymouth with a convoy, reaching the Devonshire port on the 19th. Three days later she went out to join the division of the Channel Fleet engaged in the blockade of Rochefort. On 10 August she returned to Plymouth from the Rochefort station and on the 27th she left once more for the Channel Fleet.

In September 1808 the Pompée was despatched with the Neptune 98, Captain Sir Thomas Williams, to join the British campaign in the West Indies, and in reaching Barbados on 22 October after a forty-two-day passage, she brought in with her the French brig-corvette Pilade 16, which she had captured two days earlier after an eighteen-hour chase. Cockburn was sent to command the blockade of Martinique, and from January 1809 he flew a commodore’s broad pennant aboard the Pompée with Edward Brenton as his captain. He was particularly active in leading the naval brigades ashore at the reduction of the French island on 24 February. earning praise for his delivery of the mortars and howitzers to the batteries, and following this successful undertaking, for which he received the thanks of both Houses of Parliament, he was awarded the honorary position of captain of the port of St. Pierre. Both he and Brenton removed to the Belleisle 74 in early March with orders to evacuate the French garrison to Europe. Upon arriving at Quiberon Bay on 27 April, Cockburn attempted to negotiate an exchange of prisoners, but his efforts proving fruitless, he instead landed the governor and his suite before taking all the other men to Portsmouth as prisoners of war. After his arrival home on 15 May, he struck his broad pennant to be presented to the King at a levee at the end of the month, and the Queen shortly afterwards.

Cockburn remained ashore but a short time, for he returned to the Belleisle as her captain when the Walcheren Expedition was dispatched from Spithead on 25 July, the presence of several officers his senior initially preventing him from re-hoisting a broad pennant. Once off Flushing, he commanded the gunboats with great success, and he was soon ordered to raise his broad pennant aboard the sloop Plover, Commander Philip Browne. On 15 August the French garrison at Flushing sought terms, and Cockburn was sent ashore to negotiate the capitulation. Thereafter, he proceeded up the Scheldt with his flotilla, but with a termination of the disastrous expedition being decided upon, the Plover was the last out of the river during the evacuation of the British forces. Cockburn rejoined the Belleisle and returned to Portsmouth on 14 September with the sick from the expedition, and his command was paid off in October. Going up to London once more, he attended a sumptuous dinner with other officers hosted by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Mulgrave, and he was summoned to attend Parliament at the behest of the Whig politician, Lord Porchester, to give evidence before a committee investigating the expedition.

In January 1810 Cockburn was appointed to the Implacable 74, which as the Duguay-Trouin had been captured at the Battle of Trafalgar, and after attending Court and then the First Lord of the Admiralty, he hoisted a broad pennant and sailed from Plymouth at the beginning of March on a secret expedition in company with the Imperieuse38, Captain Thomas Garth, and two smaller vessels. On 7 March, he landed two agents at Quiberon Bay with the intention of arranging the flight of King Ferdinand of Spain from the fortress at Valençay, but the mission failed when the French police were alerted, and the agents were cornered. The squadron was still of the Villaine River in early May before returning to Portsmouth, and by the end of the month Cockburn was back in London where he was introduced once more to the King.

After a brief visit to the Scheldt, where he found that reports of a French fleet at Flushing proved to be incorrect, the Implacable sailed from Plymouth to Portsmouth on 7 July 1810 to be paid, and a fortnight later, flying the flag of Rear-Admiral Sir Richard Keats, she departed for Cadiz. On 22 August Cockburn was detached on a mission up the coast to land a Spanish Army under Colonel Luis Roberto de Lacy off the Huelva River, preparatory to a surprise attack on the French at Moguer. His return to Cadiz was of a brief duration, for on 6 September he was detached to accompany two 120-gun Spanish ships, the Prince of Asturias and Santa Ana, to Havana, and thereafter to collect $2,000,000 from Vera Cruz for the Cortes. By early November the three vessels were off Puerto Rico, with reports that the Implacable had sent fifty-three of her own men to assist the Spaniards in working their ships. Reaching Vera Cruz on 23 November, Cockburn not only lost fifteen men to sickness but was also unable to obtain the treasure that had been expected, taking a substitute cargo aboard instead and returning from this mission to Cadiz on 10 February 1811. Within a month he was detached with the armed boats of the fleet to support a Spanish and British assault on the French rear, and he arrived in time to assist in the securing of prisoners following the Battle of Barossa on 5 March.

On 21 April 1811, Cockburn was sent home aboard the Druid 32, armed en-flute, by Keats and the British ambassador to Spain who was then based at Cadiz, Sir Henry Wellesley, in order to canvas the government’s opinion on mediation between Spain and her rebellious South American colonies, a move which it was thought would be beneficial to the Spanish war effort against France. Arriving at Portsmouth on 1 May, he headed straight up to London. Here he remained whilst the machines of government and diplomacy sought to form a commission that would include Cockburn, and that would attempt to reconcile Spain and her colonies. At the end of May, he was introduced to the Prince Regent at a levee by the foreign secretary, Marquess Wellesley, and he was appointed a colonel of marines on 1 August. He attended a dinner with Wellesley and Spanish notables at Apsley House towards the end of the month, and finally, on 26 November, he was ordered to raise a commodore’s broad pennant aboard the Grampus 50. Hopes that the three-man commission would soon depart proved precipitate however, and the delay continued into 1812, in March of which year he both attended a levee and enjoyed the birth of his first child, a daughter. Eventually, on 9 April, he hoisted his broad pennant at Portsmouth aboard the Grampus, Captain William Hanwell, following the replacement of Wellesley as foreign secretary by Viscount Castlereagh. Sailing the next day from Portsmouth with his two fellow commissioners, he reached Cadiz on 21 April and began discussions with Sir Henry Wellesley and the Spanish government. It soon became evident that the Cortes was intractable in its refusal to deal with all the respective parties in South America and after Cockburn had sent the brig Magnet 16 back to England for fresh instructions in June, he then returned to Portsmouth from Cadiz aboard the Grampus on 4 August, whereupon he went up to London for a long conference with Lord Castlereagh. Thus, did one of His Majesty’s most active officers waste sixteen months of his career.

On 12 August 1812 Cockburn was promoted rear-admiral, with initial reports suggesting that he would hoist his flag off the Schelde aboard the Marlborough 74, Captain Charles Bayne Hodgson Ross. Instead, after hosting the First lord of the Admiralty, Lord Melville, together with Lady Melville and their daughter, to a dinner aboard his new flagship, he dropped down to St. Helens on 18 September and three days later sailed with a convoy for Cadiz, where he was to assume the command. Pausing briefly in Torbay, the convoy was off the Scilly Isles on 4 October when the Marlborough enforced the capture of a French privateer, the Leonore 10. By the time they arrived off Cadiz on 18 October, the French had long raised their siege of the city, thereby relieving Britain from her obligation to the Spanish.

No longer required off Cadiz, Cockburn was ordered to join the war against the Americans in November as the second-in-command to Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, and he sailed from the Spanish coast to reach Bermuda in the middle of January 1813. He was still there at the beginning of March with two other 74’s, and after a brief visit to Halifax, he headed for the Chesapeake to commence what would prove to be a legendary campaign. Commanding a force that initially included four sail of the line and six frigates plus other smaller vessels, he was soon delivering mayhem and confusion to the American installations in the James, Elk, Susquehanna, and Sassafras rivers. Enthusiastically perpetrating daily attacks against the enemy, and displaying infinitely more zeal for the task than his commander-in-chief, his squadron took thirty-five vessels between 18 February and 22 March alone, and the prizes rolling into Bermuda saw fortunes being made. His tactics proved most controversial however, as illustrated by reports which soon emerged that the Americans were offering a reward of 1,500 dollars for his head, and 1,000 dollars for that of his superior, Warren. The commander-in-chief in turn reportedly condemned Cockburn’s destruction of small towns at the head of the Chesapeake, although Cockburn declared that his orders had been necessary, as his boats had regularly been fired upon from the American houses.

After a brief visit to Halifax, and having moved his flag with Captain Ross to the Sceptre 74, Cockburn took his campaign to the coast of North Carolina in early July, his smaller squadron landing troops under Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Sydney Beckwith and taking possession of Portsmouth and Ocracoke Island. Towards the end of the month the British, and in particular a company of French prisoners who had volunteered to fight the Americans, began harassing the population ashore, and although the miscreants were re-embarked, Cockburn’s offer to pay for livestock and supplies was rejected. Evacuating Ocracoke on the 16th, he sailed to rejoin Warren in the Chesapeake, and after his command had proceeded in advance of the squadron on the night of 4 August, he landed troops and a detachment of marines and sailors to take possession of Kent Island. Once they arrived, Beckwith’s troops were able to recuperate on the island until the 22nd, on which date they were re-embarked and carried down to Lynnhaven Bay. Thereafter, Warren and Beckwith sailed for Halifax, and Cockburn shaped his course for Bermuda to arrive at that island on 27 September.

After wintering at Bermuda, Cockburn returned to the American coast in the early days of January 1814, but the old and worn-out Sceptre prove to be ill-equipped for the seasonal gales, and it was only with difficulty and much pumping that she arrived with the rest of the squadron off New London in Connecticut. Fearing an attack, the American frigates harboured there cut their cables and retreated up the Thames River where they were soon frozen in, and as relations with the inhabitants of the town had previously been cordial, Cockburn decided to withdraw. Shifting with Captain Ross into the Albion 74, he left a small squadron to blockade New York with orders not to agree any challenges of a ship-to-ship combat, several of which had already been made, and he returned with the rest of his force to the Chesapeake.

In accordance with instructions from the new commander-in-chief, Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, Cockburn occupied Tangier Island to serve both as a base for the British forces, and as a refuge for runaway slaves whose flight would not only weaken the American economy, but who could also be invited to enlist in the Army. After officiating over the erection of storehouses and fortifications, Cockburn took his particular brand of warfare to the Potomac and Patuxent with two sail of the line and six frigates under his command. Divesting the land thereabouts of all military stores and posts, as well as landing marines and seamen to acquire stock, as at the mouth of St. Clements Bay in the Potomac on 23 July, he stipulated that he would not destroy property unless it was used to attack his forces, and would not take action against civilians unless they were in arms.

Calculating that it would be possible to capture the American capital, Washington, without incurring too great a risk, Cockburn co-operated with his friend, Major-General Robert Ross, and advanced further up the Patuxent, forcing Commodore Joshua Barney to destroy his flotilla above Pig Point on 22 August 1814. Ignoring Admiral Cochrane’s suggestion that they should withdraw, Ross and Cockburn’s combined force of troops and marines reached Bladensburg on the 24th and surprisingly routed a superior American army. During this engagement Commodore Barney was badly wounded in the thigh, and he would later praise both Cockburn and Ross for their kindness and respect towards him during his incapacitation. The victory led to the sack of Washington on 24 August, where Cockburn and Ross destroyed property including what is now known as the White House, the Capitol, and other public buildings at a cost estimated between £750,000 and £3,000,000. In particular, Cockburn delighted in attacking the offices of the National Intelligencer newspaper which had condemned him for his unrelenting attacks, including one false report that he had been seen on a grey horse sanctioning by his very presence a number of atrocities perpetrated against the Americans. Cockburn was later to claim that he would have burned the building to the ground, but for the entreaties of two women whose own properties would likely have been destroyed in the fire.

Despite Admiral Cochrane’s frustration at Cockburn’s failure to match his own expectations with regard to intelligence gathering, the junior admiral’s reputation soared following the attack on Washington, yet he was soon to suffer a major reverse. Ever determined to give the Americans a thumping, he attempted a raid on Baltimore with Ross, but the latter was fatally wounded alongside him in a skirmish on 12 September, and after re-boarding the Severn 44, Captain Joseph Nourse, in the Patapsco River, Cockburn re-embarked upon the Albion and departed for Bermuda.

In early November 1814 it was reported that the Albion was preparing for sea, and Cockburn sailed on the 19th for the Chesapeake to collect the remnants of his force, although it was not until 19 December that his squadron was re-assembled, allowing him to sail south along the American coast. On 16 January 1815 he took possession of Cumberland Island with the intention of fitting it out as a base to act against the southern states, but despite expectations that he would attack Savannah, he was unable to exact no more than a little plunder in attacking St. Mary’s on the border between Florida and Georgia before a flag of truce arrived on 25 February, announcing that Britain and America had agreed a peace. Departing Amelia Island on 18 March, he left Bermuda on 8 April aboard the Albion and arrived at Spithead on 4 May, having learned in the interim that he had been created a K.C.B. on 2 January.

Cockburn’s arrival home coincided with Napoleon’s Hundred Days, and whilst he spent a brief period ashore, Captain Ross began fitting out the Northumberland 74 for his flag. On 16 May he joined the official party at the funeral of Captain Sir Peter Parker at St. Margaret’s Church in Westminster, and remaining in London, on 29 June he was invested with the K.C.B. by the Prince Regent at Carlton House. Following Napoleon’s surrender on 15 July, Cockburn left London on 1 August to raise his flag aboard the Northumberland 74, with instructions to convey the defeated Emperor to his place of exile on St. Helena, and to remain there as the governor and commander-in-chief of the Cape. The party sailed from Plymouth on 8 August and arrived off the southern Atlantic island on 15 October. Despite reports that he and Bonaparte enjoyed excellent terms, Cockburn was regarded as somewhat of a harsh gaoler, and with his usual gusto he set about fortifying the island against any possible rescue of the tyrant. He remained at St. Helena until 19 June 1816 when Lieutenant-General Sir Hudson Lowe and Rear-Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm replaced him in his two offices, and by 1 August he was back in England to strike his flag.

Although the country was no longer at war, Cockburn was to prove as active on land as he had ever been on sea. In October 1816 he took ship to the Continent to visit Paris where he enjoyed a private audience with King Louis XVIII and provided minutes of his discussion with Napoleon. On 18 November he was back at Dover, from where he rushed up to London to report. He was nominated a G.C.B on 20 February 1818, was appointed a junior lord of the Admiralty on 2 April under the first lord, Viscount Melville, and was invested by the Prince Regent as a Knight Companion of the Bath at Carlton House on the 17th. In June he entered the House of Commons as a Tory M.P. in the government interest for Portsmouth after Vice-Admiral John Markham, one of his two Whig opponents, had dropped out of the contest.

A frequent speaker in parliament and a visitor to the various naval establishments, he was promoted vice-admiral on 12 August 1819, and in the following month he supervised the embarkation of two regiments at Portsmouth, which were to sail north and restore order following a series of riots, one of which had led to the Peterloo Massacre. A general election in April 1820 saw him lose his Portsmouth seat to Admiral Markham in a lively encounter, but as he was still required to speak for the Navy in the House of Commons, he was elected instead as the M.P. for the safe seat of Weobley, which was owned by Lord Bath. Even so, he raised a petition of complaint against his loss at Portsmouth, and although this was rejected, his complaint was officially considered neither ‘frivolous nor vexatious’. On 29 September he attended the newly crowned King George IV at a loyal address given by the Corporations of Portsea and Gosport, and during the performance of the National Anthem it was reported that he walked arm in arm with the monarch on the quarterdeck of the royal yacht.

Cockburn became a Fellow of the Royal Society on 21 December 1820, and he was created a major-general of marines on 5 April 1821. Throughout the rest of the decade, he continued his work at the Admiralty whilst making frequent visits to the various naval bases, undertaking his parliamentary duties, attending all manner of social engagements in London, and being presented at Court. As a reward for his long service, he was appointed a privy councillor on 30 April 1827. In the following month King George IV installed his brother, the Duke of Clarence, as the Lord High Admiral, and the Admiralty Board was disbanded; however, despite mutual misgivings, Cockburn was given a position on Clarence’s Admiralty Council. At the beginning of June 1828, he relinquished his Weobley parliamentary seat, and he was immediately returned unopposed to Parliament as the M.P. for Plymouth.

On 10 July 1828, Cockburn’s testy relationship with Clarence came to a head when he rebuked the Lord High Admiral in writing for raising his flag aboard the Royal Sovereign 100 at Portsmouth, and for issuing commissions without the Admiralty Council’s consent. Clarence demanded that both the Duke of Wellington as prime minister, and his brother, the King, dismiss Cockburn in favour of Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Paget, and he even took the liberty of summoning that officer from Ireland. Negotiations over the next week saw Wellington remind Clarence that he had exceeded his authority, and Cockburn apologise to Clarence for not raising his concerns informally. Yet with Cockburn’s fellow commissioners taking his side, and with the King advising his brother that he had erred, Clarence’s position became increasingly untenable. Determined to continue the dispute, Clarence denigrated Cockburn, whom he appears to have held in utter contempt, for ‘never having the ships he commanded in proper fighting order’ and he dispatched Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Owen to seek a retraction. Cockburn reiterated that he regretted having displeased Clarence, but that he could not renounce his concerns. Clarence was left with little choice but to resign on 14 August, and with the Board of Admiralty being re-established under Lord Melville, Cockburn became the first naval lord, this being a position he retained until the fall of the Duke of Wellington’s government in November 1830 and the installation of a Whig administration.

Cockburn maintained his presence in Parliament with the Opposition, and at the end of April 1831 he arrived at Plymouth to fight the general election in the Tory interest. A bitter contest ensued with two Whig naval officers, Admiral Sir Thomas Byam Martin and Captain Hon. George Elliott, with accusations that members of the one hundred and ninety-two electors would only vote for Cockburn in return for personal favours. Evidently the mob did not wish him well either, for his effigy was burned on Plymouth Hoe, mud and stones were flung at his party, and troops were called to escort him away from a riot at the Hustings. Even so, he came second in the contest to Martin and was duly returned to Parliament.

Harbouring expectations that he would be defeated in Plymouth at the next General Election in December 1832, Cockburn decided to resume his naval career, and with the surprising blessing of the Whig government and his old enemy, the Duke of Clarence, who was by now installed as King William IV, he was appointed the commander in chief in North America and the West Indies on 6 December 1832 in place of the late Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Griffith Colpoys. Departing London in the last days of January 1833 after an audience with the King, he hoisted his flag at Plymouth on the 28th aboard the Vernon 50, Captain Sir George Westphal, and set sail with his family two days later. This departure proved to be a false dawn however, for foul weather flooded the cabins and sent the Vernon scuttling back to Torbay. A further departure in February resulted in her returning two days later, but she eventually reached Jamaica on 11th April via Bermuda.

Once ensconced in his new role, Cockburn undertook a great deal of travelling between his various bases, as illustrated by the fact that in the spring of 1834 he visited Belize, Barbados, and Bermuda alone. On 15 July he shifted his flag to the President 52, Captain James Scott, and he was at Halifax by October.

Upon his brother’s brother-in-law, Robert Peel, assuming the role of prime minister from the Duke of Wellington back in England, Cockburn was reappointed to the Board of Admiralty under the first lord, Earl Grey, on 22 December 1834, and pending his expected return home, Vice-Admiral Sir John Beresford managed his affairs. However, Cockburn was still at Bermuda in March 1835, and when Peel’s government fell to be replaced by the Whigs in April, he was removed from the board. At the same time, in his absence he failed to be re-elected for the Plymouth constituency, being defeated by two Whig politicians. Remaining in command of the North American and West Indies station, during the autumn he undertook a visit of the Leeward Islands, and he was eventually replaced at Bermuda by Vice-Admiral Sir Peter Halkett on 2 May 1836, whereupon he returned to Portsmouth aboard the President on 6 June.

He was advanced to the rank of admiral on 10 January 1837, but his wish to return to Parliament saw him defeated at Plymouth once more in the general election of August 1837, as he was in the same election at Portsmouth. Although still prominent in the highest echelons of the state, more frequent visits were made to his residence at High Beech, Essex, intermixed with trips to London and the chairmanship or presidency of various societies.

In 1840 it was reported that Cockburn had turned down the Mediterranean command, as he could not reconcile the political and diplomatic aspect of the role with his opposition to the Whig government. July saw him presented with a silver plate exceeding one thousand guineas in value by almost one hundred officers of both the Navy and the Army, who considered it their good fortune to have served under him, yet in August his staunch regard for fairness and propriety saw him provide evidence at Bow Street against a cabriolet driver who had attempted to overcharge him after collecting him from Charing Cross and driving him around London. Unable to pay the fine, the driver was committed to the House of Correction for fourteen days.

Still seeking a return to Parliament, Cockburn was presented as the Conservative candidate at Greenwich in June 1841 but came bottom of the poll behind a Whig and a radical. On 30 August Peel became prime minister once more in the Conservative interest, and one of his first acts was to appoint Cockburn to the Admiralty Board as the first sea lord under the Earl of Haddington. Accordingly, a safe Conservative seat was found at Ripon, where Cockburn was elected unopposed at a by-election of 27 September. During his time as the first lord he oversaw the erection of Nelson’s Column and the implementation of steam and screw technology, whilst amongst other varied duties he oversaw the embarkation of Queen Victoria aboard the Royal Yacht at Woolwich for her visit to Scotland in August 1842.

In January 1843 he ruptured a blood vessel in his neck and for a time his life was despaired of, however a month later he was able to fully resume his duties, which included a visit to Portsmouth Dockyard in August and a trip to Antwerp aboard the steam vessel Black Eagle in the following month. During April 1844 he took the waters at Leamington, and he was back with other board members on the annual tour of the dockyards, including Plymouth and Pembroke in September 1844, this being a task he undertook every year.

In January 1846 the Earl of Ellenborough was appointed as the first lord of the Admiralty, and soon significant differences with Cockburn and other board members began to surface. With the government’s defeat in June 1846 Cockburn left the Admiralty, although he remained the M.P for Ripon until the General Election in July 1847. Meanwhile, he was reported to be ill in the autumn of 1846, yet was happily ‘almost convalescent’ by December. He became the Admiral of the Fleet on 1 July 1851, at which time his health was again a cause for concern, and on the death of his brother James on 26 February 1852 he succeeded to the family baronetcy. In December he was well enough to attend the Duke of Wellington’s funeral, and he was present at a concert given by Queen Victoria in Buckingham Palace in July 1753.

Cockburn died on 19 August 1853 at Leamington Spa, and he was succeeded in the family baronetcy by his younger brother, the Dean of York. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, London.

On 28 November 1809 he married his cousin, Mary Cockburn, the daughter and co-heiress of Thomas Cockburn of Jamaica, and the couple had issue one daughter in March 1812 and another in January 1816 who died just a year later. On 28 April 1817 a third daughter was born. His sister-in-law married Vice-Admiral Charles Bayne Hodges Ross. He owned residences at High Beech, Essex, and in Cavendish Square, London.

Cockburn enjoyed the early patronage of Vice-Admiral Sir Joshua Rowley and Admiral Lord Hood, who were friends of his family, and he also benefited by being related to the Pitt family. Of ‘pleasing affable deportment’ and ‘perfectly free from duplicity’, he was highly educated, intelligent, and knowledgeable, determined, courageous, confident, sensible, and a strict disciplinarian who was severe yet just, and able to rise above petty disputes. Brilliantly skilled at his trade, his energy, enthusiasm, and zeal knew no bounds, and throughout his career he made every effort to make his countries’ enemies suffer. As a young officer he was described as ‘penurious’ and later on as ‘sprightly and fashionable’. Paradoxically, although some thought him of a mild manner, affable and temperate, others thought him ‘harsh and overbearing’, especially in later life when his renowned toughness brought accusations of haughtiness, conceit, and bullying.

In parliamentary circles, his kinsman by his brother’s marriage, Sir Robert Peel, said of him that ‘he was a very fine fellow’. Assiduous in his governmental roles, he spoke clearly and authoritatively without being a fiery orator, although he was criticised for ‘absurd conduct’ in not accepting the viewpoint of George Canning over a naval affair in 1824, and at the time was described as ‘ungovernable’ with ‘his head turned by the dominion he holds at the Admiralty’. During his early parliamentary career he spoke merely on naval matters, and at the time of his death he was labelled ‘The Wellington of the Navy’.